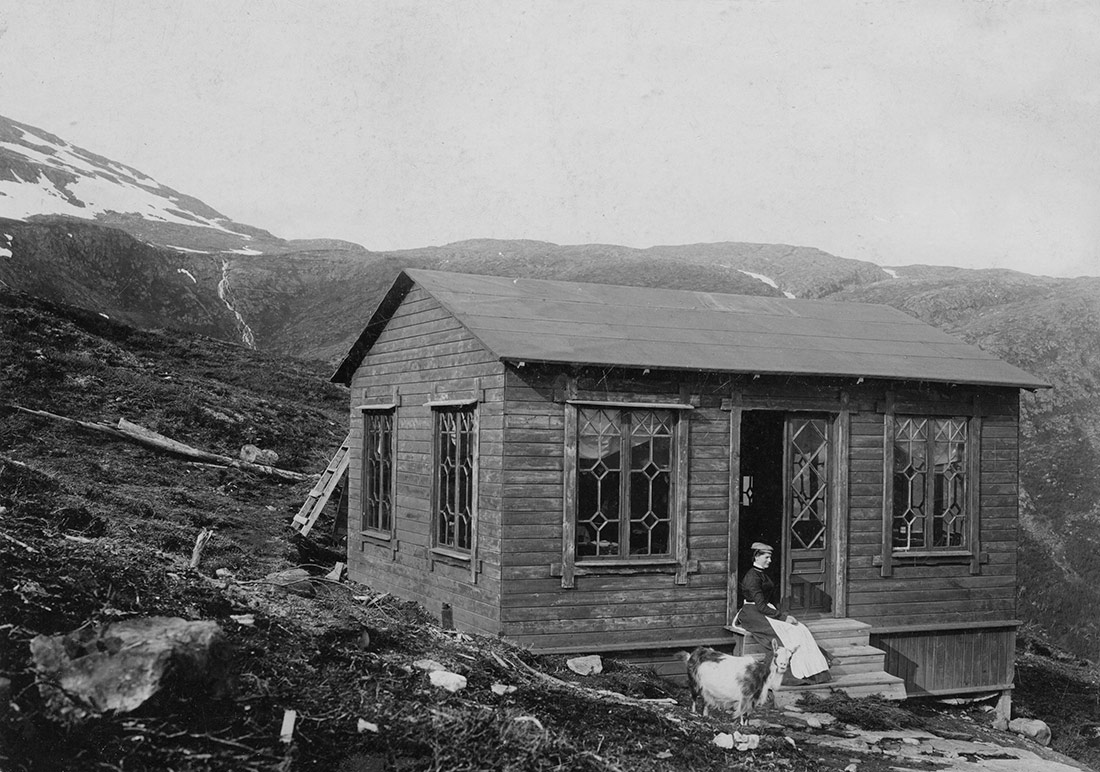

Mountain landscape | Digitalt Museum | Public domain

We’ve reached internet saturation point. The exhaustion and fatigue are clear to see. Even so, we are ever more hooked on screen time. Is it possible to escape from the thunderous noise of social media? Can we find other ways of conceiving of and relating to the internet that leave space for thought?

“I am less interested in a mass exodus from Facebook and Twitter than I am in a mass movement of attention: what happens when people regain control over their attention and begin to direct it again, together.”

Jenny Odell

I check my Twitter and Instagram during my breaks from work, or maybe by checking them I force myself to take a break from the umpteenth email that I need to send today. On the train, I read the latest trending article on the current controversy of the day to understand all the threads of comments and sides that have been taken on Twitter. I do it because I enjoy knowing who’s said what, seeing who makes the sharp, ironic comment that will get my like, or, in the case of flagrantly unfair situations, my retweet.

Since the arrival of the monopolistic social networks, we’ve seen how time has progressively sped up. Time spent waiting, connecting, consuming. Now I skim through texts looking for the key ideas, or the equivalent, I listen to podcasts and videos at one and a half times the speed. The images pass before my eyes in mere tenths of a second and I curse the poor internet connection at certain points on the train journey. And it’s not just this whole digital vortex itself, it’s the importance of being there. Of having a profile, of being visible. A part of our online presence is based on creating contacts, on networking, which we can do by presenting a book or by sharing part of an article that has made an impression on us as a story or a tweet. As the sociologist Manuel Romero wrote, Twitter has become our LinkedIn, where we share articles, professional achievements and talks or workshops. Social networks have become showcases for people who conduct research, write, create podcasts, and for artists, tattooists and designers. To the extent that we’ve turned our lives towards constant productivity and 24/7 availability, we’ve turned the human body into an asset that we can exploit for profit, whether social or economic. In one way or another we contribute towards social media saturation, we feed the bulimia of images with our likes, selfies and memes. The problem isn’t the internet itself, but the fact that the most popular digital spaces are managed by private enterprises whose primary goal is to capture our data and attention for financial gain. And the algorithms of these platforms, which are hidden from sight, design the way we relate to each other. We socialise within a very specific structure that rewards whatever keeps us hooked to scrolling, consuming screen time; whether it’s a video criticising the capitalist system and consumer society or the latest controversy on Twitter.

As we extend ourselves through our screens, it’s easy to fall into a well of exhaustion and fatigue. To wish to disappear or leave the vampire castle, as Mark Fisher said. At a time when capitalism is able to appropriate all those discourses that are critical towards it, and where even creativity has been subordinated to productivist principles, I think it would be interesting to revisit some ideas about silence and nothingness.

The philosopher María Zambrano talks of how silence is needed to germinate man and the divine, in her book of the same title, El hombre y lo divino (1955). For her, art, creation and thought emerge from nothingness, from the silence of the soul. We require instances of recollection to reflect on what surrounds us. Not just a few minutes reading different opinions on Twitter to decide where we should base our viewpoint, but empty spaces, soundless and timeless cavities. Zambrano writes that nothingness “is the supreme resistance”. Taking it out of its context, this idea leads us to investigate ways of resisting the attention economy, of not falling into the exhausting game of self-exploitation as Juan Evaristo Valls Boix proposes in Metafísica de la pereza (2022) through different non-productive instances such as partying, sleeping, decreating or striking.

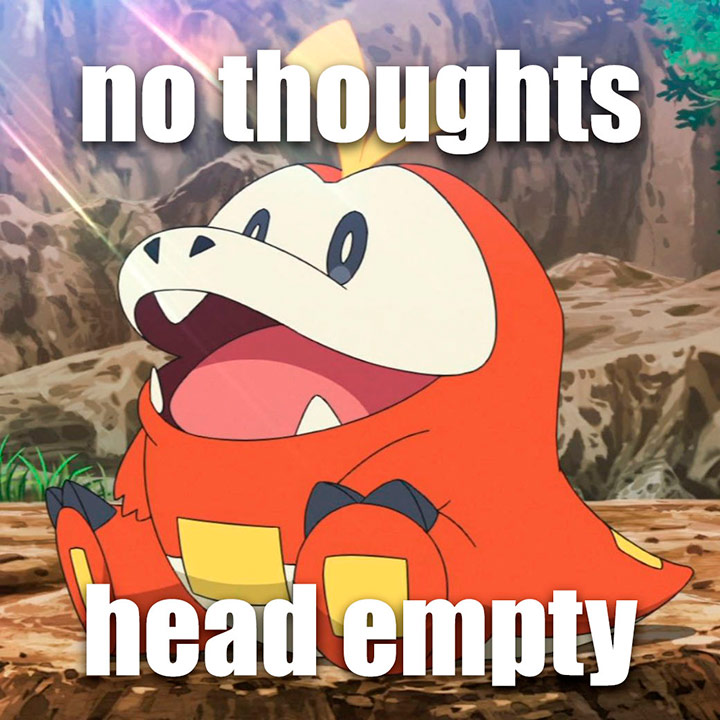

In fact, the nothingness and silence of which Zambrano speaks have a mystical component that reminds me of the catchphrase “No thoughts, head empty”, often accompanied by a screenshot of some character smiling faintly and gazing into infinity. This internet catchphrase is used to imply that someone is either stupid or speechless. Of the characters that best embody this phrase, I like the Pokémon Fuecoco, from the video games Pokémon Scarlet/Violet (2022). I’m inclined to think that this goofy-faced red crocodile is not really a poor idiot, but that it symbolises someone who has managed to turn the thunderous noise of social media into silence; who has been able to open up a space of almost mystical revelation and silence the mind using Zambrano’s Poetic Reason. And the fact is that uninterrupted exposure to images can also become a kind of silence, a background murmur, as Carson McCullers showed with the radio in The Member of the Wedding (1946): “The radio had stayed on all the summer long, so finally it was a sound that as a rule they did not notice”. Similarly, saturation of images could turn into white noise, leaving us immune to excess. This is where this interpretation of “No thoughts, head empty” comes into play, the feeling that comes over me as I look at TikTok before going to bed and I let myself be rocked by the anaesthetising and infinite scroll of kittens, books and gameplays as I tumble freefall down the rabbit hole, like Alice. I’m not entirely sure whether we can turn the amalgamation of digital content into a faint murmur, but we do have to keep looking for other ways of thinking and relating to the internet so that we still have space for thought.

As always, platform capitalism has already taken over the discourses of disconnection through self-help books, coaching programmes and digital detox holidays. YouTube is full of motivational talks and videos of people explaining how to cut down on screen time (as we continue to give away minutes of our time in watching them) or how the latest internet retreat has brought them inner peace (although they always come back online to talk about it, they never give it up completely). The capitalisation of disconnection and minimalism make us see that the right to disconnect is not recognised for everyone, and it becomes clear that it is, in fact, a privilege for many. What’s more, disconnection is sold to us as an essential break to recharge our batteries before getting back into the system; simple tools in the service of productivity that will never provide a solution to the basic problem of the attention economy. And if all the entrepreneurs and employees of the big tech companies in Silicon Valley bring up their children in screen-free environments, they must surely see something bad in everything they’re creating.

Although capitalism has taken over the need and tendency to slow down and disconnect, this doesn’t mean that such need arose within the neoliberal system. Indeed, its roots can be found in the utopian socialism and anarchism of the 19th century, where people were already moving into communes as a response to the economic and social system that was being imposed. The discourse of disconnection forgets or hides the fact that the internet has been a key space for the dissemination of non-mainstream discourses, the organisation of collectives and the creation of communities that provide mutual support for all those people who are surrounded by a hostile environment. We can’t reject a tool that offers us a way to connect with so many realities and stories. Disconnection is not necessarily a utopia. Disconnecting for once and for all is neither a desirable nor a universalisable option. Disengaging and withdrawing from the world is a decision that can only be made by individuals or small groups of people, and it involves no responsibility for the environment and the society that is left behind. As the artist Jenny Odell proposes in How to Do Nothing (2019), rather than abandoning the world and hiding away in an isolated refuge, we need to learn to listen to our surroundings and redirect our attention. To replace FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) with NOMO (Necessity of Missing Out) and try to open up new non-vertical spaces where we can continue to build digital communities. A good example of such communities can be found in the fandoms that have been organising and sharing their worlds on the internet for years; from fanfics to Wattpad and Archive of our Own to Tumblr. Odell encourages us to go down the rabbit hole out of sheer curiosity and not just to find mountains of sterile, anaesthetising content.

I still remember 18 November 2022, a day when it seemed that Twitter would go down at any moment and we would witness the burial of one of the most powerful companies in platform capitalism. That day we read Twitter in hardcore mode, waiting for it to vanish, while Elon Musk fired 50% of the workforce in the style of Kendall Roy in the series Succession. Amidst the mad pace and memes of what was supposed to be Twitter’s final hours, there were tweets about mass migrations of users to the free and open-source software Mastodon. The farewell messages gave us a spark of hope; the beginning of a new way of inhabiting the internet and staying connected without the mediation of the attention economy. Were we really heading towards a decentralisation of social media? The journalist Alba Correa commented that the future of social media is to move towards a more atomised internet, segregated by interest groups and obsessions. Perhaps we will lose the common walls of cultural and ideological battles, but if there’s a chance of having a digital connection that’s more organic and, above all, less anxious and more environmentally sustainable, we should begin to explore the new spaces that are being built. In the meantime, we can continue with the mantra “No thoughts, head empty” as an antidote to the excessive attention demanded by the major platforms.

Joan Salomon | 07 March 2023

Molt article i bones reflexions.

Poc concluents i massa obertes. Massa prudents i poc propòsitives en el món de tuiter.

Esta clar que la virtut de la prudència i el seny no són d aquest nou món. I alhora és l únic que tenim clar que quedarà i al final ens salvarà.

La sabiduría i la prudència per damunt la velocitat i la competència.

Perdent de golejada acabarem guanyant. Però quant? Segurament massa tard o massa lluny. Encara.

Leave a comment