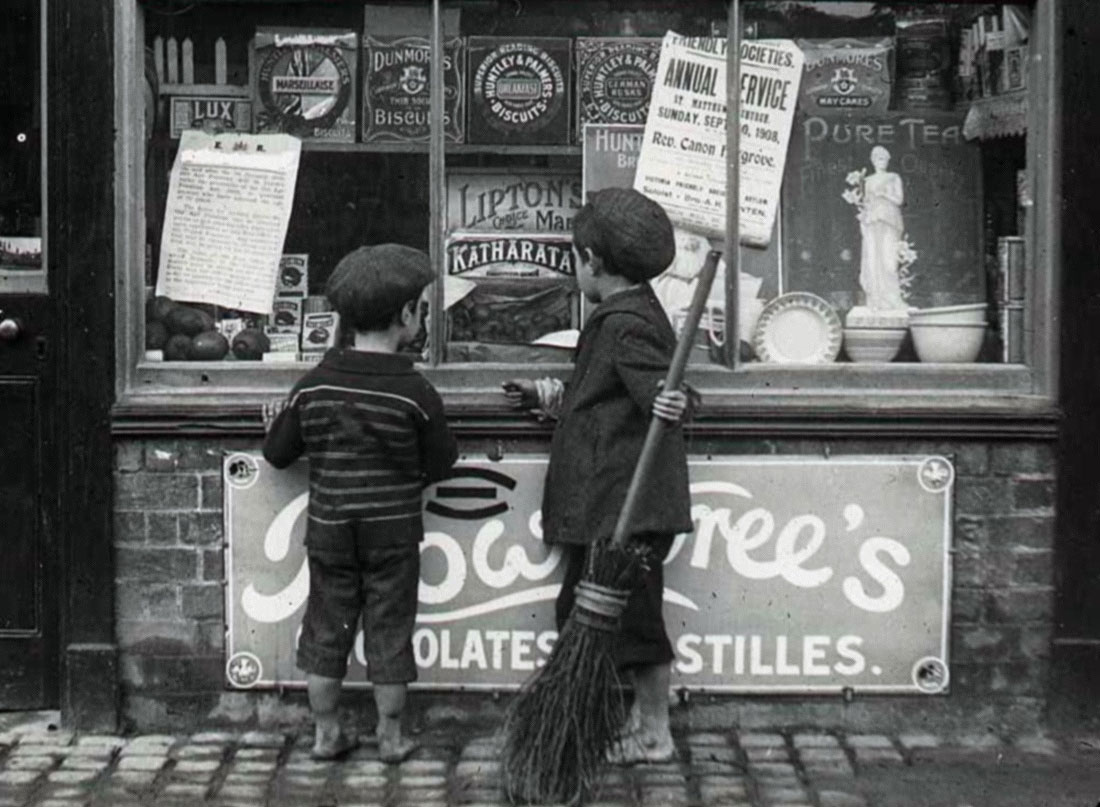

DTwo children looking at a window of a chocolate shop. CC-BY-NC-SA, Paul Townsend.

“A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” This flippant aphorism attributed to Steve Jobs is chilling and bellyache-inducing, and it perfectly encapsulates the aim of neuromarketing. While traditional marketing supposedly seeks the best way to meet consumer needs, neuromarketing shares the same goal from the point of view that Jobs’ words suggests: it studies the way the brain works in consumer purchasing decisions, particularly the part of the brain that we cannot express rationally.

Let me start by saying that I can’t think of a single benefit that makes the idea of neuromarketing positive for a society. At best, it allows a powerful few to maximise profits by producing the ideal campaign based on the tactics of neuroscience. I just don’t know is whether it is bad, disastrous, or macabre. In an era in which we are all slaves to voracious consumption and the mechanism that drives programmed obsolescence has jumped from machines to our own minds – “I don’t want this anymore, it’s old fashioned” – the last thing we need is studies that allow us to understand how to attract the gullible and give them that extra little nudge that drives them to buy the latest car, the newest television, the next smartphone. Gilles Deleuze described marketing as the new form of social control through which man is no longer confined, but in debt. Neuromarketing is a further turn of the screw, in which Deleuze’s hypothesis becomes a nightmare right out of Ray Bradbury: Live fast, die young, but waste all your money, please.

They Live, We Sleep. CC-BY, Eduard V. Kurganov.

But conspiranoiacs should not get excited just yet, given that there’s nothing new under the sun. Neuromarketing is neither magic nor a new form of mind control. It simply studies a consumer’s purchasing decisions using techniques developed years ago in the field of neuroscience. I’m sorry to tell them that neuromarketing is not a cover for a scenario like the one in the film They Live, in which Roddy Piper finds sunglasses that enable him to see the extraterrestrial reality in which we live, controlled by subliminal signs ordering us to “obey, buy, reproduce” hidden in travel ads and news reports. None of that. Neuromarketing is just the same old consumer spirit, trying out the latest technological fad. Yes, it’s scary; but as far as I’m concerned what makes it scary is the consumer aspect, not the technology.

The discipline of neuromarketing seeks to access the part of a consumer’s decision that is not conscious and cannot be expressed rationally. It tries to find out what emotions a particular ad or product triggers without asking consumers, given that to a large extent they themselves would be unable to say. In other words, neuromarketing hooks us up to the polygraph and records our bodily responses in order to detect what we feel – rather than what we think or say – about a product, brand, or service. A lie detector that can squeeze out the essence of our decisions.

This means that even if ultra modern, high-tech tools and techniques are used to measure consumer responses and behaviour, they can’t do anything new for now. From eye-tracking to discover how we behave in response to what we are looking at (not what we are seeing, because we could be daydreaming), to measuring physiological signals such as heartbeat and skin conductivity, by way of studying the movements of our facial muscles and, particularly, recording our brain activity by means of different procedures: none of these can read our minds, let alone manipulate them. For the time being, the very idea of divining our thoughts is totally unfeasible, given that we can’t even identify an emotion using medical imaging technologies. It is true that we can measure responses such as tonsil activation in response to fear or hate, that the insular lobe appears to be involved in revulsion or rejection responses, and that the performance of the dopaminergic system is usually boosted in the presence of positive emotions. Nonetheless, there are no reliable systems by which introducing a particular brain activation image leads to a specific response such as “happiness”, “sadness” or “anger”. And even if it were possible to instantly and accurately identify the emotion that somebody is experiencing, it would be useless. Just as you like coffee and I prefer peach juice, a particular product or advertising campaign will not trigger the same emotion in all human beings. Different strokes for different folks.

SMI Eye Tracking Glasses. CC-BY, SMI Eye Tracking.

SMI Eye Tracking Glasses. CC-BY, SMI Eye Tracking.

But we’re talking about the present and the short-term future, of course. Where will we end up if we continue along this path? Will the “buy button” – that Holy Grail of consumer culture that enables us to understand all the factors which unfailingly lead to a purchase – cease to be a myth? The design of new tools, and the combination of existing ones that are starting to be implemented, promise a thrilling future for all those who want us to us to buy, buy, buy. It won’t be long before the neuromarketing experts get together with the Big Data guys and start crossing individual data with large-group trends, extracting stratified profiles of potential customers along with customised strategies.

Because the fact is that we are connected to the internet all day long, and this makes us a never ending source of resources for companies. I’ve seen meetings at which big hospitals and pharmaceutical multinationals dealt with patient information as though they were swapping trading cards. Sure, individual confidentiality is upheld, but here’s a friendly tip: read everything you sign. We all share whatever opinions pop into our heads on Twitter, Facebook, blogs and other media, without realising that those opinions are worth money. A lot of money, if we’re talking about a lot of opinions. We have inadvertently become free consultants, telling companies about our habits, tastes and preferences. And that’s just the beginning.

If the hyperconnectivity trend continues – and we certainly don’t seem to be backing down — every step we take will soon be monitored. The bracelets we use when we go running and our super-cool smartwatches will provide real-time information on our exact location and our heartbeat rate, for example. And as computational capacity increases even further, it’s not hard to imagine that companies will be able to use these devices to deduce our stimulation in response to a particular ad or product. The technology would simply have to detect the fact that we are looking at a screen, record the moment when a particular video or banner is displayed, monitor our heartbeat or skin conductivity – which is an indirect sign of excitement: “we get goose bumps” – and save the data. Multiply this process by a thousand, or a hundred thousand, and we can start to draw conclusions.

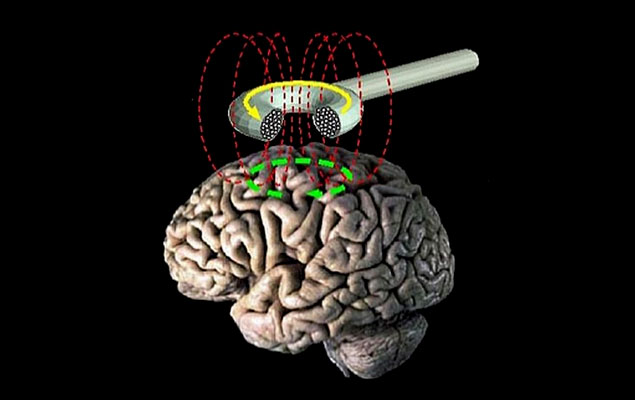

And wouldn’t it be fun for companies to stimulate our purchasing decisions rather than just read them? There’s no need to jump to a distant future in which cyborgs are the norm and our purchase commands go straight to whatever chips are in use. There are already a lot of studies on how non-invasive techniques such as transcranial stimulation can regulate our emotions. Activating certain electrodes, for example, can modulate the functioning of a part of the prefrontal cortex linked to the part that controls negative emotions. In layman’s terms, the things that made us sad or afraid will make us less sad and afraid. Wonderful, right? But because money talks, a technique with enormous potential for treating serious depression could end up being a catalyst for our future permanent, artificial happiness. For the time being, this technique requires highly controlled conditions, and the coil or the electrodes have to be positioned extremely accurately, very near to the head. But science constantly advances and who knows what the future will bring in ten or twenty years time. Perhaps by pressing a little button, the passer-by who enters a store, through the security gates, will instantly feel happier at the sight of the products. An idyllic future, no doubt about it.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation. Public Domain, Wikipedia.

In a world in which companies only think about increasing profits year after year, it’s hard to imagine how far professional ethics go, and the point at which we simply become indicators. In Fight Club, Tyler Duran said that advertising has us “working jobs we hate to buy shit we don’t need.” Perhaps we could start by considering this statement instead of continuing to think about buying even more shit that we need even less. And perhaps things will start working better then.

Diana | 19 April 2016

Hay mucha razón en lo que dices, me llamó mucho la atención esa ultima frase porque si no somos todos, al menos mas del 80% de la población se siente atraída por el consumismo ya sea por la moda, por capricho o porque simplemente le generaron la necesidad de consumir un producto o servicio. Debo admitir que aunque a veces esas necesidades que son creadas han dado resultados y beneficios, otras son en realidad servicios o productos innecesarios que solo nos da un instante de satisfacción una vez los tenemos.

Gracias por compartir artículo.

Sandra Pickering | 24 April 2016

I paused at this comment: “I can’t think of a single benefit that makes the idea of neuromarketing positive for a society. At best, it allows a powerful few to maximise profits by producing the ideal campaign based on the tactics of neuroscience.”

What about the many organisations (including some businesses) using neuroscience to help people do the right thing?

Maryna | 30 December 2016

Do you think in future the will be that almost invisible border between neuroscience really helping people & marketers to do things better and neuroscience directly manipulating and controlling humans brain? And is this border will excise, how humanity will distinguish “bad”s and “good”s?

Leave a comment