Sorry We’re Open, Amsterdam. Joe Futrelle. CC-BY-SA

Once again this year, we packed our bags and headed to MuseumNext, the annual European conference on technology and innovation in museums, which was held in Amsterdam. At this year’s conference, the financial crisis and the major funding cut-backs that it has entailed gave a major boost to an idea that has always hovered over MuseumNext, but now rang out like a mantra: true change is a change in attitude, not technology. Thus there is a need to re-think ourselves in the new cultural context and to work on strategies for medium and long-term change.

How can we adapt to change? Ideally, by pressing “PAUSE” and thinking about where we want to go and how to get there. Two of the MuseumNext keynote speeches focused precisely on the process of transformation undergone by two museums that have recently been closed due to refurbishment: the Rijksmuseum (which reopened last April after ten years), and the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York (which plans to resume its activities in 2014). The renovations at these institutions went hand in hand with a reassessment of their missions, their roles and their future strategies. What we can deduce from their experiences is that we can no longer consider a museum to be container made up of watertight compartments. Instead, a museum encompasses the physical building, the programming, the collection, the community and the online activity, with a long-term strategy that charts a future course and connects everything together.

But museums have to work in different contexts and financial situations, and for many of them the idea of shutting down in order to stop and reconsider their position is still a luxury and/or a utopia. The inertia of the day-to-day running of a museum can easily prevent us from looking towards the horizon. Nonetheless, if true change really is a change of attitude, it means that we have to be conscious of the new context, and gradually incorporate new approaches, small innovations, test things, learn from mistakes… So even if large-scale reforms are not be on the agenda at your museum, this article also reports on some of the ideas, projects, processes and working methods discussed at MuseumNext that prove that small changes are powerful too.

Closed for Renovation. The importance of (re)inventing oneself

The Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum building in New York is closed for renovations, but a striking message on its website (which remains very active) informs us that there is still plenty of great stuff going on inside. In Amsterdam, the Director of the museum’s digital strategy, Seb Chan, talked about all the things that can be happening in a museum even when it appears to be inactive. As Chan’s idea of a museum is an overall whole that encompasses the physical and digital dimensions, he sees the temporary closure of the Cooper-Hewitt building as an opportunity rather than a problem. These are the keys to its transformation:

- Define a goal: “Embed digital in the organisation and the fabric of the building.” The Cooper-Hewitt building is being renovated and it won’t reopen until 2014, but the museum’s team is still producing activities in other spaces in the city. They are also taking advantage of this time (and others) to digitalise everything they do.

- Build a team. The Cooper-Hewitt is committed to training and to building strong teams (“hire people smarter than you.”)

- Take irreversible decisions. Although it may seem risky, Chan defended radical decision-making to signal the start of a period of change. In just three months, the Cooper-Hewitt released its entire collection and made it accessible to the public.

- Speed up production: “Any utopian project inherently entails error,” said Chan. So this is what they’ve done at Copper Hewit Labs: prototype, test and experiment with projects without being afraid of making mistakes.

- Mixed collaboration. Being in contact with other cultural agents and working with them is essential. In this case, for example, the museum decided to donate the collection to the Google Art Project.

- Programme regular launches. When generating products and prototypes, new projects should be launched at a regular pace: from digitalising old catalogues to creating affordable, user-friendly e-Books, and unofficial experiments with the collection, such as theCuratioral poetry initiative and the Berg Littler Printer. It’s what Chan calls Institutional Wabi-Sabi: the coexistence of imperfection, chaos and change in an institution’s projects.

- Focus on long-term change and back curatorial practices rather than the technology itself. For example, the Cooper-Hewitt online connection is connected via links to other museums, Wikipedia, libraries… “We have to give space on the net to everything and everybody, and use new technologies to curate the world,” Chan said.

- Success indicators? More visitor diversity, longer and return visits, greater user satisfaction, internal innovation and improved capacity of the collection are the indicators used by the renewed Cooper-Hewitt.

According to Seb Chan, we should stop seeing museums as authorities and start to see them as providers of services in which technology acts as an amplifier. Chan ended his presentation by clearing up a point for his listeners: he had not been speaking about the future of the Cooper-Hewitt, but about the future of us all. You can see the full presentation here.

The Rijksmuseum, or opening up your collection in order to inspire people

Last April, after ten years of renovations, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam reopened the refurbished rooms of the building and launched a powerful digital and communication strategy that Peter Goergels, Internet Manager and Editor, summed up as follows: “Connecting people with art and history.” This is not just an advertising slogan, it is a goal: to maximise the reach of the collection. The Rijksmuseum has digitalised and released 125,000 works from its collections, making them available to users. A painting transformed into a tattoo (like the ones that Goergels handed out after his presentation), for example, or clothing customised with paintings by your favourite artist. Simply download your favourite work and use it however you wish.

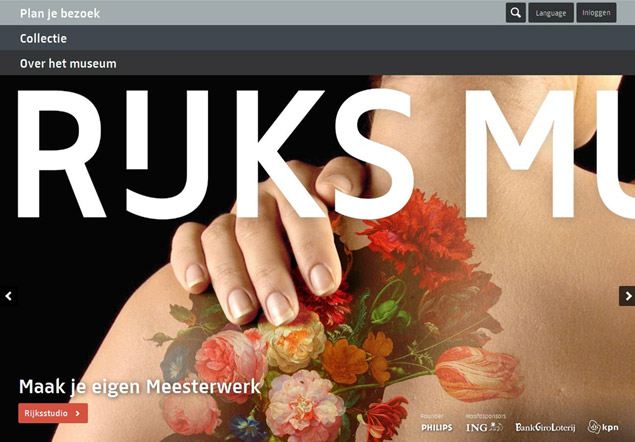

Rijksmuseum new website

Another of the gems of the new Rijksmuseum is its website: a brand new, highly visual design inspired by tablet interfaces. Goergels explained that they approach design from a holistic point of view: a good concept is required as well as experimenting with and using new possibilities. They also prioritise images, they simplify, and they place value on quality and innovation. A year and a half after the launch of the website, it has surpassed all expectations: they have received great user response, won international awards, and attained a high level of participation (110,000 personal collections, 210,000 downloads of artworks).

The museums of the future: a new concept, a new attitude

Along similar lines to Chan’s institutional “Wabi Sabi”, other speakers also referred to the importance of innovation, error and prototyping. The mantra continued to ring out: the true challenge of museums is not technological; it is about attitude and culture. For those who want to tackle cultural change, the Museum Scenarios 2020 report, presented by Bridget McKenzie (Flow Associates) suggests some keys to the socio-economic situation that is affecting Europe and will continue to do so over the next few years: unemployment, funding cut-backs, increased cultural tourism, rapid technological change… The report also considers global trends such as the warming of the planet, diminishing resources, citizen indignation, and increased democratic awareness… factors that museums should take into account when they look towards the future. The study, which focuses on British territory, questions the way museums currently operate, and presents alternative models: the “Green Museum”, which promotes other economic models and cooperative management, the “Unmuseum”, a museum without walls (without a building?) that would be based on people prepared to pay for culture, and a combination of the two, a “Disruptive Museum” that would operate as a hub for sustainable communities, invest in eco-social innovation, and promote art and creativity in order to conserve communal assets and also as a catalyst for change. You can see the full presentation here.

Kathy Fredrickson (Peabody Essex Museum) agreed with Chan in that confronting the challenges of the future means taking the long journey of constant innovation (“to infinity and beyond!” was the title of her presentation). Fredickson believes that the future model will require having an idea and starting work on it immediately: prototype, prototype, prototype. It’s not an easy road, say Carolyne Royston (Imperial War Museum) and Claire Ross (Center for Digital Humanities, UCL), who discussed the lessons they had learnt during the year they had spent on their project. Research and development (R + D) does not bring instant profit. It is a process that challenges the way our institutions work, integrating new methodologies and the knowledge that is derived from them. They offered some advice: ensure that the scope and scale of the projects are doable within the established timeframe, the assigned budget and the available resources; design a project that fits naturally into a broader programme; clearly define the success indicators and evaluation system from the outset; set aside sufficient time for communication within the organisation and the industry.

Other related presentations

- The Future is Incremental. Developing Digital services in unstable conditions. Presentation by Andrew Lewis from the Victoria & Albert Museum.

- The Happy Museum. A museum that takes future challenges into account: sustainability, dialogue, ecology, etc.

- Happy Museum Project. Museums and Happiness: The value of participating in museums and the arts. Report.

- Digital Museum as a Platform. Presentation by John Wang (National Museum of Denmark).

- Digital Strategy Maps for Museums. Presentation by Conxa Rodà (MNAC).

Community, our reason for being

Many cultural managers are (or should be) aware of the fact that museums are no longer one-way prescribers, and that it is necessary to take the people that we work with into account. But few institutions implement and integrate these ideas into their operational model (at least among the ones we are familiar with). In this sense, the working method used by the Science Gallery in Dublin, which was presented at MuseumNext by its Director Michael John Gorman, is a paradigmatic case of cultural management in an organisation that not only takes into account the needs of its target community, but also works with and for it: it is its reason for being.

The initial “limitations” of the Science Gallery – a small space, no permanent collection, a target audience of adults – became opportunities when the museum decided to actively involve the community in producing activities and projects. Following Sean McDougall’s concept of Ablative Design (allowing people to do things and working with them, drawing on their proposals), the museum’s mission is to become a creative platform (rather than a container of content). Gorman mentioned Medialab Prado and the Ars Electronica Future Lab, in which the design of the buildings themselves helps to transmit the idea of spaces for creation, as an inspiration for their own project.

Michael John Gorman explains the working model of the Science Gallery using this slide.

At the Science Gallery, they distinguish between three levels of community participation: visitors, participants and community. Participation is integrated at the start of the project rather then being added on at the end, as is often the case. Some of the keys to this way of working are: a strong focus on broad interdisciplinary topics, open calls asking for ideas from the community, working with different types of networks (universities, laboratories, research groups), and organising activities that don’t necessarily take place at the Science Gallery. Their challenge is to strike a balance between a strong brand, a rigorous narrative, their ethos, openness, and the high speed of change.

Some Science Gallery projects that Gorman discussed in his presentation include: Love Lab, Elements, Barrage, Infectious and Hack the city.

Even though it was the last talk on the last day of MuseumNext, the presentation How Not to Involve Users by Marlene Ahrens (National Museum of Denmark) turned out to be useful and inspiring. Ahrens talked about the mistakes that the Museum made when it organised the exhibition Europe meets the world, which included a participatory section in which visitors were asked to answer five questions. A complicated participation interface and an insufficiently clear idea of the project limited the active involvement of visitors. Planning participatory projects far enough ahead, integrating them into the exhibition, and placing ourselves in visitors’ shoes in order to consider whether it makes sense to call for participation are some of the lessons learnt, which could also be applied to the working methods of many other similar projects. Marlene Aherens’ talk was an exercise in honesty (explaining when things go wrong) that we think should be more common in congresses and conferences, where most speakers talk about the success of their projects.

Other related presentations

- Mediamatic. A research and development centre that explores new ways of organising resources and audiences. It combines public activities with the idea of a work-laboratory. The results of their work-experiments are published in open source.

- DMA Friends. A free community project by the Dallas Museum of Art Friends.

- No more Lightweight Interaction. A talk by Linea Hansen (National Museum of Denmark) in which she shared her recipe for the proper use of Facebook, based on her own experience. Key idea: think about your content and participatory projects as you would about a gift: would you yourself want it?

- Participation at Scale: Leveraging incentive and gamification to promote museum engagement. Presentation by Robert Stein (Dallas Museum of Art).

- Amsterdam Public Library. This institution didn’t participate in MuseumNext, but we took the opportunity to visit, and found a paradigmatic example of an inclusive space that invites action and participation.

3D Printing and Responsive Design

Just as augmented reality, mobile applications, and (overrated) QR codes were mentioned in many of the talks at last year’s MuseumNext Barcelona, this year’s most talked-about technology was 3D printing of objects. At the Conference opening event, designer Maaike Roozenburg presented the Smart Replicas project that she is developing with the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam and other centres. Thanks to 3D printing technology, we can now obtain wonderful reproductions of art objects and pieces dating from thousands of years ago. The way in which museum visitors and art lovers interact and learn may be about to change thanks to the fascinating replicas of venerated (and protected) art objects. Moritz Neumuller presented a case study of the use of 3D printing in museums, particularly in terms of improving accessibility. Kamer Maker, a 3D printing project applied to public space, was also presented.

As the rate at which cultural content is accessed on multiple screens rapidly increases (some 25% of young Europeans aged 18 to 24 have an Ipad or a tablet at home), so does the need to integrate Responsive design, a web development and design technique that allows the web environment to respond to the user: computer, smartphone or tablet. In the practical workshop Go Tablet, Matthijs der Meulen (Q42) and Ebelien Pondaag, Paul Stork and Anna Offermans (Fabrique) gave us some useful tips to keep in mind when planning or commissioning a design application for tablets:

- Your finger is not a mouse: use large buttons and links to make browsing easier. Don’t hide important information.

- Users expect tactile interaction. Use it well.

- Focus on the content (use text and images to make browsing easier).

- A mobile device can be used in many different places. Keep this in mind when you design the application (people could be using the app at the beach, in the sun, stretched out on the sofa…)

- Simplify: include only important content. Capture the attention of users with the information that is truly important and useful.

Other interesting projects that we discovered at MuseumNext Amsterdam

- The Big Internet Museum: A museum that only exists online: free, with curated exhibitions and exhibitions programmed by users. According to Dani Polak, art director and ideologue of the project, the Big Internet Museum is not turning a profit, but it offers a new way of producing and sharing culture that breaks away from the traditional model of museum management.

- The Web Lab: Joining forces with Google to develop an exhibition project can lead to impressive results, such as this series of interactive experiments to understand how the Internet works. You can discover Web Lab in person at the Science Museum in London (until 20 June) or play with it virtually (using the Chrome browser, of course ;-)) This is one of the initiatives that clearly shows how exciting exhibitions can be when physical and virtual spaces play a key role in the user’s experience.

- Audio Tour hack. A studio that produces creative approaches to art and museums.

- What’s Now, What’s Next, What’s Within your Budget – Oonagh Murphy, from the University of Ulster, travelled to New York to observe and study how some of the major museums work, and then put together some ideas (which are not too difficult to implement and do not require huge budgets) to help small museums learn from the “big guys”. You can see her presentation here.

- What’s Next for Web TV for Museums?

- How to collaborate with startups A study by DosDoce presented by Javier Celaya, which looked at how museums and startups can work together and help each other. During the MuseumNext conference, DosDoce also published Museums in the Digital Age.

- How Hirst spin paintings deepened Tate Kids engagement and reach from pre-school to teens. Presentation by Mar Dixon and Sharna Jackson (Tate Kids).

We’ve come back from Amsterdam brimming with ideas and energy with which to face an uncertain future. Once again, MuseumNext has reminded us of the importance of integrating users and the community within our project, of defining medium to long-term working strategies, and of the arduous path of innovation… This year, we noticed that many more of the talks revolved around working methods and processes of change, rather than presenting one-off projects. Perhaps the “change of attitude” mantra is gaining strength… and suddenly, we see the crisis as an opportunity.

“The new cultural practice suggests a process of transition in which nobody is exempt from the need to re-examine their operational criteria: the ideas around which projects are created and conceived, working methods, production processes, styles of representation, the ability to be sustainable or not, and ways of communicating, disseminating, and sharing knowledge. The claim to processes that make it possible to deepen the democratisation of culture, that is, cultural access to information, production equipment, and reproduction, is starting to be an inalienable right. And this right must not only be capitalised by the cultural industry.”

Networks, Processes and Platforms, Juan Insua.

Leave a comment