Computer chess. Source: Wiley Wiggins.

In response to the digital challenges that museums and galleries have to grapple with, organisations and their staff need to adjust to the new ways of thinking and working in a digital-physical world. This blog post provides invaluable insight into some of the practical strategies that institutions can implement or learn from in order to boost the effectiveness and success of their change initiatives.

Digital technologies have become an everyday fixture in museums, and they are here to stay. They are altering the paradigm of the world of museums, which, like any other organisation, must shake up their business models and organisational structures and fully embrace the digital landscape if they are to remain relevant in today’s society.

In the pre-digital era, when information was scarce and precious, museums, libraries and archives were the spearhead and the driving force of the accumulation of knowledge. Back in the 1930s, a surge in the amount of available information led to a greater need to classify information and make it more accessible by all available means. The author H. G. Wells and his notion of the ‘world brain’, described as ‘a depot where knowledge and ideas are received, sorted, summarized, digested, clarified and compared’ (cited in Rayward, 1999) inspired the World Congress of Universal Documentation held in Paris in 1937 to discuss these issues, and to decide to use microfilm –the most advanced technological device at the time– to make information available on demand. Fast forward to 2013, and we seem to have found much better and incomparably faster media for storing and sharing information: more than any scholar would ever be able to read, sort, summarise, digest, clarify and compare in his or her lifetime.

The internet boom in the public sphere in the 1990s drastically transformed and improved access to information about museums and their collections. But although museums were traditionally considered ‘temples of knowledge’, they are now facing competition from many other content providers in similar fields. They are expected to become catalysts for dialogue, as well as broadcasters of information. At the same time as institutions are opening up to their users, the internal gates and walls between departments are also crumbling away. This leaves museums with a window of opportunity to apply the same democratic principles of co-creation and collaborative culture within their walls.

Institutions need to transform themselves in order to function more effectively in the digital age. Many museums recognise that their systems of organisation are not suited to the digital world. Similarly, experts are finding that siloed organisational structures hinder progress towards a more digital and participatory culture (Rogers & Seidl-Fox, 2011). As a result, we are seeing a trend towards organisational change, in an attempt to transform institutional effectiveness within a digital dimension.

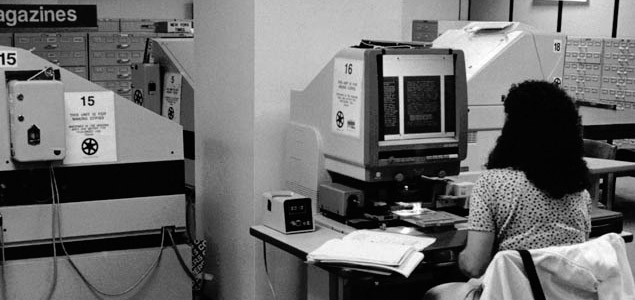

Woman at microfilm reader/printer, Ohio University’s Alden Library, 1994. Source: Ohio University Libraries.

But where should this digital transformation begin? You can start by defining the problem in business terms, asking yourself and your colleagues the following questions:

- What is the organisation trying to achieve?

- Why do we need digital transformation?

- How is this change likely to affect the organisation?

- What would this process look like in an ideal situation?

- What could possibly go wrong?

If you accept that digital transformation will be a long-term, incremental change (Luecke, 2003) and follow these basic guidelines, you will be on the right path to enhancing your institution for the digital age.

Create digital leadership

The key factor for successful digital transformation is the acquisition of digital skills at the executive level. You can make this happen by training up your current leadership in digital skills, training up your digitally savvy people in management skills, or creating a new digital leadership role from scratch. Whoever is making decisions about the use of digital technology within the museum needs digital experience, authority and seniority to establish strong digital leadership.

Rethink funding and financing procedures

Funding for digital activities is still mainly opportunistic and reactive rather than strategic and based on real user and organisational needs. Funding tends to be attached to individual projects, which are often more closely aligned to the funders’ needs than to organisational priorities. In these circumstances, it is almost impossible to strategically plan and schedule digital activity and production. Only a change in financial procedures and the inclusion of a digital budget in annual financial forecasts alongside other planned activities will help make your wishes come true.

Become a networking organisation

The critical success factor for a museum’s digital presence is the creation of a networked organisational structure (Kotter, 2011) in which flexible, multidisciplinary teams work together towards shared objectives. The interconnectivity of the web and the omnipresence of digital technologies make it difficult, if not impossible, to plan for digital activity within siloed hierarchical organisations. Strive to become a networked organisation and you will see the world in a new light.

Digital strategy isn’t, but strategic planning is a must!

Digital strategy is about harnessing the opportunities and managing the risks that go hand in hand with the digital world, and tapping into its potential to deliver on shared business objectives. If a digital strategy is to be effectively implemented, it should arise from your overall organisational strategy. Even if this means re-writing your overall organisational strategy from scratch!

Focus on mission, but listen to your audiences

Conduct surveys, focus groups and usability testing, and use digital analytics to focus on the elements that users like and to improve aspects that they have issues with. Becoming more user-centric and user-led means investing in audience research in order to gain valuable insights into the motivations, behaviour and attitudes of people who visit museums online or physically. Carry out research, act upon your findings, combine them with the organisational objectives, and strive to create digital products and activities with them in mind.

Follow a digital production roadmap

The most important document that a museum has to create and keep up to date is its digital production roadmap, which should record all the digital activities in progress, regardless of the stage they are in. This document helps to communicate the current status of digital production projects in real time, and encourages decision makers to monitor the work and its progress in relation to organisational objectives

Establish shared objectives

Before a new idea makes it onto the digital roadmap, it should meet a set of clear criteria that are derived from your organisation’s key digital principles, objectives, and digital KPIs. After the organisation’s overall mission, the next most important aspect of a coherent decision-making process involves setting up broader organisational objectives and ranking their importance.

Polish the digital production processes

You should consider writing, reviewing and agreeing on new documentation, raging from content management user manuals and publishing style guides to accessibility and mediation policies and workflow diagrams. These documents will become the hard evidence of your new processes and procedures.

Participation starts inside the museum

No matter what organisational structure you start off with, moving away from the traditional project mentality and towards a collaborative approach, and embracing holistic digital production will enable better integration of digital activities and more efficient and effective delivery.

Invest in digital capacity and skill building

Digital skills are not a core competency of museum staff, so they need to be specifically developed. But improving the digital literacy of existing staff needs is not just about providing training. Internal meetings are also an opportunity for digital staff to share their knowledge with other colleagues, by showing and explaining digital production documentation such as wireframes, functional specifications, workflow diagrams, and analytics reports. Regular internal communication about the digital aspects of the organisation, as well as a public programme of talks, seminars and meet-ups around relevant topics can help to establish a truly digital culture within an organisation.

Devolved authoring or devolved publishing route

Museums can choose to decentralise content authoring and publishing, and to implement a model of layered editorial control that makes different departments accountable and responsible for their own content. Devolving authorship across the museum could have a positive outcome in large organisations that are trying to engage with many diverse audiences. But it comes with many caveats and may not work for every institution. In order to succeed, it needs to be strategically planned and carefully managed.

Digital technologies are powerful tools. But don’t forget that digital is not the main driver in digital transformation: the museum staff is in the driver’s seat, and digital technologies are its passengers.

References

Arthur, L. (2013) “Why You Should Consider Hiring a Chief Digital Officer, And Why Now.” Forbes website. Consulted August 1, 2013.

Dana, J. C. (1926) “In A Changing World Should Museums Change?” Special Libraries Association. Consulted August 19, 2013.

ICOM (2007) “Development of the Museum Definition according to ICOM Statutes (2007-1946)”. ICOM website. Consulted August 23, 2013.

Kotter, J. (2011) “Hierarchy and Network: Two Structures, One Organization.” Harvard Business Review Blog. Consulted August 17, 2013.

Luecke, R. (2003) Managing Change and Transition: Practical Strategies to Help You lead During Turbulent Times. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing.

McGovern, G. (2013) “Why it’s so hard to be customer-centric”. New Thinking blog. Consulted August 1, 2013.

Lim, M., Griffiths, G. H. & Sambrook, S. (2010) “Organization Structure for the Twenty First Century.” Proceedings of INFORMS conference. Austin.

McGovern, G. (2013) “Strategy & Online: How online is changing the game and the playing field for strategy development.” Customer Carewords website. Consulted August, 1, 2013.

Rayward, W.B. (1999) “H.G. Wells’s Idea of a World Brain: A Critical Re-Assessment.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science 50. Consulted August 10, 2013.

Rogers, N. & Seidl-Fox, S. (Eds.) (2011) “Libraries and Museums in An Era of Participatory Culture: session report.” Institute of Museum and Library Services. Consulted August, 12, 2013.

Simon, N. (2010) The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0.

Smith, K., Morrison, A. & MacDonald, F. (2013) Leading Digital Transformation: Recommendations for Charity Chief Executives. Brighton: Cogapp.

Stack, J. (2013) “Tate Digital Strategy 2013–15: Digital as a Dimension of Everything.” The Tate website. Consulted July 30, 2013.

Stanford, N. (2007) Guide to Organisational Design: Creating High-Performing and Adaptable Enterprises. London: The Economist

Stein, R. (2012) “Blow Up Your Digital Strategy: Changing the Conversation about Museums and Technology.” The Museums and the Web 2012. Consulted July 30, 2013.

Villaespesa, E. & Tasich, T. (2012) “Making Sense of Numbers: A Journey of Spreading the Analytics Culture at Tate.” The Museums and the Web 2012. Consulted August 3, 2013.

Leave a comment