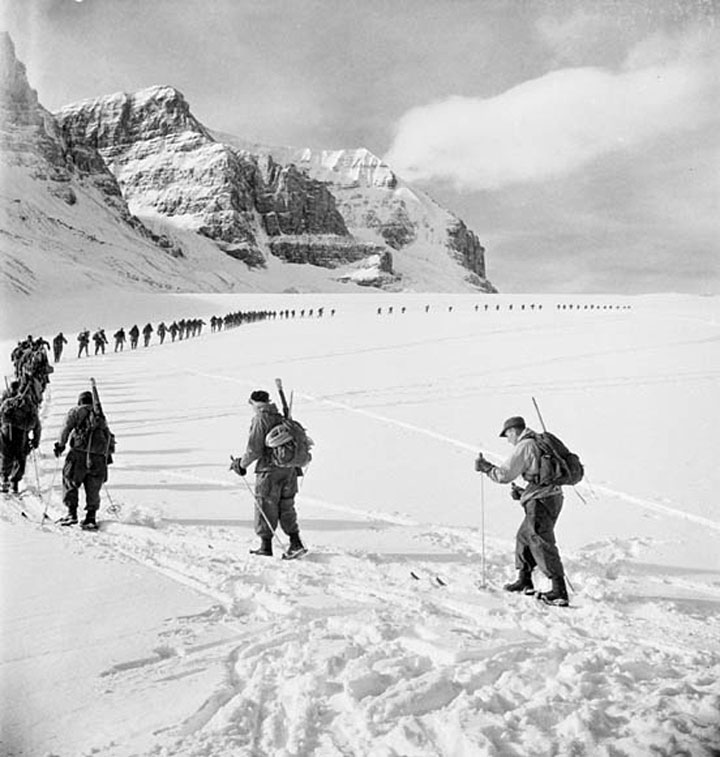

Lovat Scouts, mountaineering section, ascending the tongue of Athabasca Glacier in the Rockies, 1944. Source: Library&Archives Canada

Theories, thoughts and tests: are we on the cusp of a golden age of experimentalism or have we reached a Peak Lab? The article Age of Social Public Labs is part of the collection dedicated to LABS published in Long+Short published by Nesta UK; here we translate a fragment of it.

Almost a hundred years ago, in 1916, Wilbur C Phillips, the original American “social inventor”, as described by the founder of the US National Bureau of Economic Research, published a plan for a National Social Laboratory. It was a radical proposal using civic participation as the driver for public services, seeking to do for children’s health what John Dewey’s Laboratory School had done for education. 16 cities responded to the offer of $90,000 for a three-year experiment ($25m in today’s money, four times the size of this year’s Bloomberg Challenge). Cincinnati won, and created a “living lab”, staffed with a team of eight, covering 31 blocks of the city.

By 1920 the initiative had helped create a comprehensive public health system, a century before Obamacare and even 30 years before the establishment of the NHS. Though it was an unalloyed success, the lab was eventually killed off by politics. Phillips’ early membership of Eugene Debs’ Socialist Party, the nervousness sparked by the Bolshevik revolution, the threat to the Mayor’s political base and bureaucratic opposition within the Cincinnati Health Department all conspired to lead the City Council to cut the programme’s funding after the proof of concept stage.

It’s a helpful corrective to our modern-day myopia to remind ourselves that the labification of everyday life is by no means new. To fully understand the lab phenomenon, it needs to be viewed through the wide-angle lens of history.

With two thirds having been created in the last five years, the idea of labs for social change seems to have morphed in the wake of the economic crisis from method to movement, and from metaphor to meme. Psilabs (public and social innovation labs to the uninitiated) work on the idea of applying the principles of scientific labs – experiment, testing and measurement – to social issues. Depending on who you talk to, these can range from the lab-like initiatives of the Behavioural Insights Team (whose ownership is split between Nesta, the Government and the organisation’s management) and the Education Endowment Foundation, which run rigorous experiments, to less evidence-based approaches like France’s Region 27 and Denmark’s Mindlab, which, taking a design-led approach, could be anathema to anyone with hard science background. Despite the panoply of methods, it was definitely in 2014 that #psilabs – as they’re grouped on Twitter – emerged from the margins. In the space of year we got a manifesto (The Social Labs Revolution), a couple of manuals (Labcraft and i-teams) and, in May, a global meet-up (at MaRS in Toronto).

Type the term “social lab” into Google’s N-Gram and you will see two spikes in its usage in the 20th century: the Depression, and the oil crisis of the 70s. It’s not difficult to see the attraction that labs promising to prototype the future hold when current institutions are failing – and whose very failure generates for labs (like their close relatives, the thinktank and the startup) a vast gene pool of talent in today’s reserve army of the underemployed. Here at the fag-end of our own lost decade it’s perhaps wise to ask whether we are poised on the cusp of a new golden age of experimentalism, or rapidly approaching Peak Lab?

The salutary story of Phillips’ “social lab”, which almost got off the ground in Cincinnati, reminds us that labs – designed though they may be as islands of innovation – never really exist in a vacuum. In our time social labs are, in some sense, the continuation of change by other means, where other efforts at transformation have stalled. An earlier generation’s response to this breakdown was the “long march through the institutions”: part reform from within the system, part pressure from outside through the creation of new social movements. Swapping this (by definition) long-term strategy with the two-week iterative cycles of agile social change is superficially seductive – particularly in an age of instant graphification.

But positioning the lab, not as a new toolbox, but the change-lever of our time could stretch its usefulness to breaking point. Dismissed as yet another fad, labs could easily suffer the same fate as design thinking, that went from problem-solving’s new holy grail to being declared a failed experiment by Bruce Nussbaum, its one-time biggest proponent, in less than a decade. The naïve techno-optimism of some lab evangelists is easily satirised. In Dave Eggers’ novel The Circle, a mega-lab that bears a passing resemblance to Facebook’s or Apple’s soon-to-be-unveiled cathedrals of creativity, someone thinks it’s a good idea to try gamifying homelessness. At least in this case it’s to solve it. In Cory Doctorow’s darkly humorous paean to MIT, the short-story Petard, the over-caffeinated “chaos monkeys” of the R&D lab casually decide to evict people in a randomised controlled trial.

To survive and prosper social labs need to be less lab, and more social: helping people find their own solutions in unique situations rather than discovering universal laws to scale and to replicate. We need more labs. But we also need a mixed ecology of innovation spaces – the trans-disciplinary studio, the Utopian experiment, the engineers’ test-bed, the artists’ colony – blending the science and tech with the art and craft of the (seemingly) improbable. Never forgetting that, in the end, it’s still politics that will determine the limits of the possible.

Original article at The long and short.

Leave a comment