The old paradigms that supposed humans and their technologies to be the transformational epicentre of nature are thrown into question by the new philosophical currents. Theories that understand the human being as just another part of a broader network, a reality that we cannot perceive or experience completely and that therefore question the division, or hierarchy, between human (subject) and non-human (object). In this article, we review some of the best-known ones such as the Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory, flat ontologies and object-oriented ontologies (OOO) and Timothy Morton’s hyperobjects Theory, among others.

A new virus has become an unlikely element that is currently paralysing or moving entire countries. Populations of jellyfish that are obstructing the flow of cool water at nuclear power stations and almost causing collapse, as has been seen from time to time in various regions (for example, in 2013, in Oskarshamn, Sweden). Algorithms that prevent the circulation of certain types of information, and strengthen other contents. Massive floating islands of plastic that cause maritime blockages, constitute a biological threat and are the result of the sum of millions and millions of bags, pieces of packaging, straws, bottles and drinks containers.

Despite humans having played some role in the events mentioned, for example, in developing them, it cannot be said that the world is created and modified exclusively by human beings. This is even more true as we find ourselves at a point in history in which old paradigms that assume that humans and their technologies are the transforming epicentre of nature, are being threatened and are being questioned. Not only from the realm of public opinion, but also from the different sciences.

At least in the last thirty years – despite the roots of new currents always having longer roots in the past: we would be talking, as noted on occasions by philosopher Luis Montero, about Spinoza, Montaigne or even Plutarch – attempts have been made to find new theories that explain how certain changes and certain types of non-human relations occur, after inconsistencies were found in the act of putting human beings, or their technology, as a collective appendix, at the centre and foundation of history and of the world.

One of the first hypotheses that became famous was actor-network theory, sociologist Bruno Latour (from the 1980s onwards). More a method and a toolbox than a deeply elaborated system of thought (in the sense of “ontology” or logically justified philosophical system), this principle proposes the understanding that people as individuals rarely have the capacity to transform or deform the environment, or to influence it; whether this relates to the material (for example, transforming a street) or the intangible (for example, causing new public policies to be drawn up or generating new cultural customs).

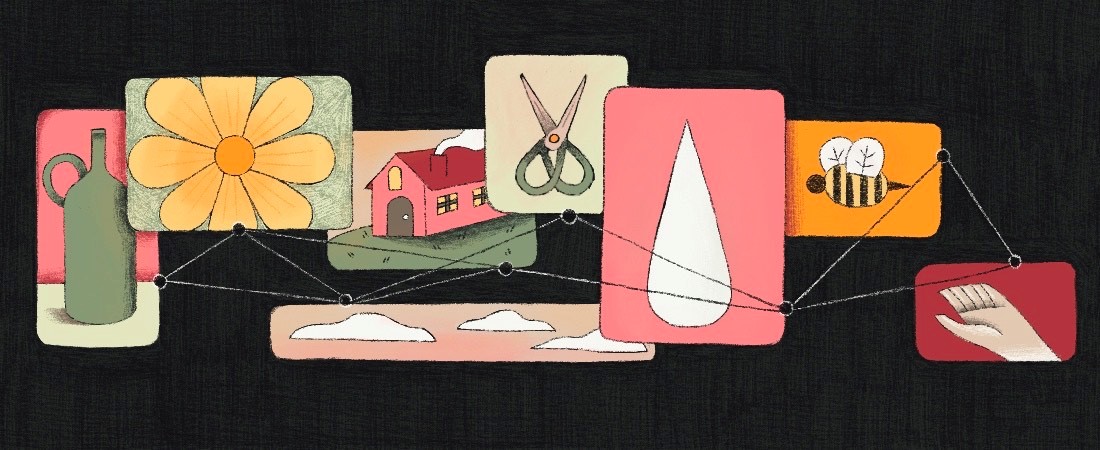

In reality, actor-network theory proposes that any person – but also any object – is submerged within a network, if not a system, of people, of collectives of people, as if they were objects (for example, a governmental institution or a company) and of non-human things (machines, plants, etc.). These networks can be defined with research, and they can give an idea of those entities that have the capacity to act on their own environment and context. For example, we could not imagine Greta Thunberg without the network to which she belongs: different activist organisations, such as Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion, which at the same time are made up of thousands and thousands of people scattered everywhere, and of digital media. Nor could we think of her or of the different movements without the relations between these thousands of people and institutions and people with power, or without the narrative and the action promoted by the same digital media.

Despite it having had many responses in the sphere of academia, the main value that this theory brings us is that things and people cannot be understood within a linearity of events, neither in their individuality nor from the supposed power afforded to them by the simple fact of being human and having awareness. Furthermore, it has contributed to an alternative challenge – already latent in academia – to many conventions and classical assumptions of the Humanities and Social Sciences.

Towards the end of the nineties, some new visions appeared, such as speculative realism, flat ontologies and new materialism, which aim to question the deepest layers of culture, but which have turned out to be obsolete when tackling the complexity of the world and its new challenges; when tackling what has put up visions of the world that, although they do not seem to be, are used by us in everyday life (as explained in the first part of this article!).

For many centuries, and to a certain degree based on Greco-Latin traditions, in Europe, North America and other areas that inherited these cultural paradigms, attempts have been made to understand the nature of reality. One of the classic philosophical problems has been how we access reality: the senses (such as hearing, touch and vision) and rationality have a many limitations.

For example, nowadays we know that there are things that we cannot see directly, such as infra-red, x-rays or atomic and astronomic scales. Nor can we hear sounds situated outside of the range that runs from 0 to 130 decibels. Nor can we perceive so many other things that, while the machines we manufacture try to make all of this inaccessible world accessible for us: for example, in reality we see infra-red photos of the core of the galaxy because they have been converted into colours that we can see.

In the 20th century, it was also added that reasoning and abstraction, in the sense of critical thinking, were other key tools for looking in greater depth at what is real. And here, philosophy was already starting to divide itself between the capacity for observing and taking awareness of phenomena (phenomenology); the way that we generate knowledge, in the Western sense of justifiable and certain beliefs, such as the Gettier problem (epistemology), and the nature of things and reality (ontology).

Certain movements have questioned conventions on the nature of reality and the division between the human (subject) and non-human things (objects, very much in generic): if we only deal with the illusions of our ego or with the projection of self onto the environment (as would be proposed, in broad outline, by Hegel) or if the reality exists but our sense and/or our language do not let us access what is real and raw (again in broad outline, Kant).

Flat ontologies (promoted by Levi R. Bryant, Ian Bogost, Tristan Garcia, Timothy Morton and Jane Bennett, among other others), and also including the object-oriented ontology (OOO) of Graham Harman, and with connections with other more feminist and gender-based views such as those of Karen Barad, note that in reality it makes no sense to generate a dichotomy between subject (the person, human or whoever experiences reality) and the object (the opposite, normally animals, objects and things in a broad sense).

Furthermore, they try to integrate, once more, the fact that each individual is not a single entity, isolated in the world, but belongs to networks and systems, and this also reverts in the experimentation of what is real. Furthermore, we cannot suppose that we human beings can access all reality nor, in consequence, manage all the changes and that means, or so they imply, that it makes no sense to put ourselves in a situation of moral or categorical superiority in relation to the rest of the things in the world. We will never be able to put ourselves inside the heads of other people, or of animals, nor experience life as plants, or even less have an idea of what “the life” is like of inanimate objects or how an artificial intelligence “perceives” life. For this reason, they are called “flat” ontologies: in opposition to the philosophies and explanations of the real generated by universal or total hierarchies.

Thus then, an interesting way of exploring reality, as proposed by flat ontologies, involves trying to evaluate the real by assuming that all are objects even though, evidently, we can see types of different objects with different properties and, clearly, people also have different capacities.

In addition, vibrating in tune with actor-network theory, “things” cannot be understood without their relationships, without the different types of interactions that they establish between them, even if these are not intentional (assuming as evident that a table has neither intentionality nor willpower). Thus, at the same time, this may imply that different objects, by integrating different relationships and interactions, generate new objects. This connects with Morton’s proposal regarding hyperobjects: one hyperobject could be the climate, and climate change too. Thus, therefore, we can be means within a greater system, and if we want to continue making use of the object-subject dualism, reality demands of us that we consider as subjects (not in a legal sense) certain inanimate things such as, for example, a forest or a platform-app.

Although these articles are introductory – and on this occasion we have only put the spotlight on a small number of new currents –, these new perspectives in philosophy are, right now, relevant questions in fields such as the digital and post-digital arts (the issue is addressed at each edition of the Transmediale festival), in architecture (proven by the fact that one of the founders of this ontological view, Harman, works at the Southern California Institute of Architecture) and in design (for example, the new currents related with the critic).

This is just one of the numerous fronts from which the central role of human beings is being questioned. We find ourselves facing an “anthropodecentrist” moment. And, therefore, perhaps it would be the time to introduce gender perspectives into it, such as feminist or decolonial epistemologies, or the post-humanistic view. Now that people are talking about the “Digital Humanities”, could it be that the Humanities are also something innovative in a situation of crisis and transformation? Whatever the case, and despite any possible holes in the theory or argument that they may have, these new currents are indicators of an urgency for changes of paradigms that impact at the same time on our values and our way of relating with the world around us in order to manage ourselves better.

Leave a comment