Ethel Merman seated at typewriter, 1953 | Walter Albertin, Library of Congress | Public domain

The Internet has created a new context for language and, for the first time, informal language has become the norm. We write in lowercase or we misspell certain words to create a specific effect. We personalise language so we can use it as a vehicle to express our personality.

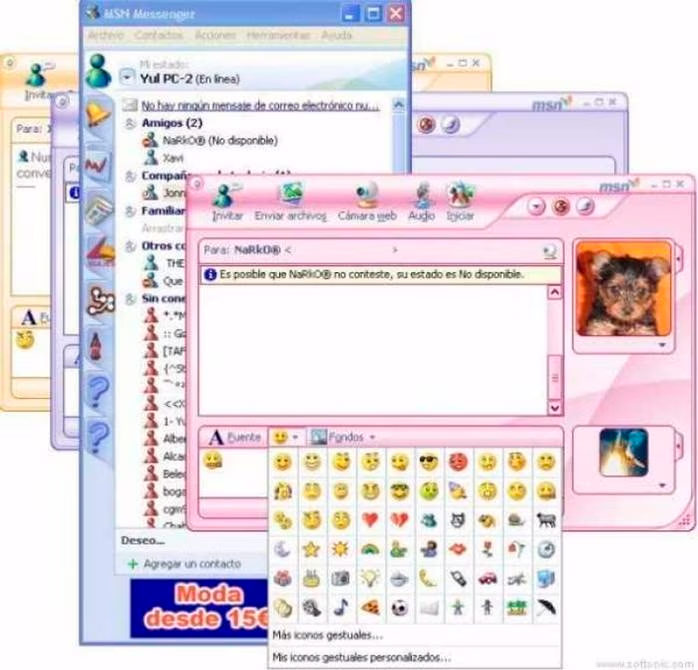

Back when everyone still had to use Messenger, conversations were very different to what they are nowadays, not because of the content, but because of how they looked. Letters in any type of colour, size or font, with animations and free-style spelling and punctuation were the order of the day for online messaging. Each conversation formed a unique visual mosaic that looked more like the pages of a Geronimo Stilton book than anything else.

Messenger revolutionised the way people communicated online, at least for one particular generation, while also giving rise to a very specific aesthetic. The chats on this platform were not only a place for communicating, they were also places where you could be creative and personalise your digital identity, where the visual possibilities were practically endless. Messenger had turned online conversations into a kaleidoscope of words and sounds, were messaging was practically a gamified experience. In MSN for example, to get someone’s attention you connected and disconnected, generating a whole load of windows and noises that were also a form of non-verbal communication.

softonic.com

Now that the Internet has consolidated its position as a universal tool, for the first time in history, informal language has become the norm. In her book Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language, Gretchen McCulloch, a linguist specialised in the Internet, writes that “The Internet and mobile devices have brought us an explosion of writing by normal people. Writing has become a vital, conversational part of our ordinary lives.”

The Internet offers us new, highly dynamic forms and styles of written expression. The linguist David Crystal was already predicting in 2002 that this new digital environment would bring about a linguistic revolution: “Revolutions in the history of language are rare events indeed. Spoken language emerged some 50,000 years ago; then, 10,000 years ago, we encounter the emergence of writing; now, in our time, we have seen the emergence of a third medium: electronic communication through the Internet.”

It’s not often that a new context is created for language. As McCulloch says, nowadays “we all make linguistic decisions all the time.” We spend our days writing, whether it’s projects or reports, emails or WhatsApps, tweets or messages on Instagram. It’s obvious, however, that the codes and the way we write change depending on who we’re communicating with and the application we’re using. In particular, McCulloch points out that “sometimes, we decide to align ourselves with the existing holders of power by talking like they do, so we can seem rich or educated.”

This is what a lot of women do in their jobs. There’s a joke that’s always popping up on TikTok where users explain how at work they’ve started to “write emails like a man,” tired as they obviously are by a hostile climate and a masculinised work environment. But what exactly does it mean? What does it mean to write an email like “a man”? According to the videos, it means doing away with any kind of niceties and not including any exclamation marks. “Hello Paul!” becomes “Hello,” and “Please don’t hesitate to ask if you have any queries!” simply doesn’t exist.

@garbage.bird No emotion. Just business. #LinkBudsNeverOff #OREOBdayStack #fyp ♬ Love You So – The King Khan & BBQ Show

In this case, as McCulloch would say, these women are adapting to the linguistic codes of other groups, but this is not always the case. She therefore highlights that “sometimes, we decide to align ourselves with particular less powerful groups, to show that we belong and to seem cool, antiauthoritarian, or not stuck-up.”

In the book Chilean Poet by Alejandro Zambra, one of the characters, Vicente, says when thinking about poetry that “all the lines start with lowercase letters, because that’s how poems are these days; starting lines with uppercase letters, especially the first line, is a sign of aesthetic conservatism.”

Although he’s referring to new trends in contemporary poetry, this can also be extrapolated to the general aesthetic of modern-day language. In fact, this feeling of wanting to seem antiauthoritarian, or not stuck-up, as McCulloch says, fits in perfectly with the trend of doing away with capital letters when writing on mobiles or computers.

McCulloch says that a lot of young people choose to write with minimalist typography to create “a specific effect,” but what kind of effect? Does it appear more casual, more effortless, more aesthetic or even more artistic? In fact, some mainstream music artists have followed this trend when naming their work, for example Ariana Grande, with one of her most successful albums “thank u, next,” or Taylor Swift with her most intimate albums “folklore” and “evermore.”

just lost the idgaf war (i turned auto caps off) pic.twitter.com/HlITANS7mO

— Ethel Cain’s gay intern (@jambettestan) February 27, 2023

In a forum on music, fashion and art, a user wrote in 2016:

i’ve noticed that people type like this. i’m on the fence about it. sometimes i think it’s cool. sometimes i think it’s phony, as in it makes people look like they’re trying too hard to be artistic. what do you think of it? i guess it’s minimalist, which i like. i also think that maybe capital letters aren’t necessary at all. why do capital letters exist anyway? capital letters seem elitist to me, as if they want to be better and more special than all other letters. plus, it’s unnecessary effort to constantly press the shift key on the keyboard. i’m honestly feeling a lot lighter and more relaxed typing like this. i guess this is more like the equivalent of sitting down on a couch with people and talking to them while enjoying a good drink by a fireplace.

However, aesthetic decisions about digital language aren’t limited to taking caps off your mobile keypad settings. In the same way that some people opt for this minimalistic approach, some go the opposite way – hopping between lowercase and incorrectly placed uppercase letters and using the latter to highlight emotions, or using abbreviated spelling.

It’s a very expressive and emotionally charged style that is reminiscent of the Messenger and Fotolog chats and the Internet of the early noughties, one that has certainly been influenced by the return of 2000 or Y2K fashion, which has been trending for months now – in AAAaaaalll the Inditex stores. One of the biggest fans of this style is Rosalía, who often writes LIke thIS on social media. On her album Motomami she even titled one of the songs CUUUUuuuuuute, which obviously isn’t the same as saying “Cute” or “cute.”

“You need to take a course to know how to write the names of artists and their songs,” wrote the journalist Jordi Bardají in El País a few months after the release of Motomami. When Rosalía chose this style of language, many of the more conservative cultural critics interpreted the singer’s choices with the paternalistic label of “infantile” or “immature,” as if Rosalia hadn’t meticulously planned to write this way to fit in perfectly with the most up-to-date codes of modern digital language.

@rosalia27/1

All these distortions of language prove that language is alive. McCulloch writes that the form, the grammar, the words, the vocabulary and the tone will “keep changing,” it’s inevitable, and we will continue adapting “in spoken language, in text messaging, in whatever the next version of social media is.” In this article we’ve focused on verbal language, but we’d have much more to talk about if we extended our analysis to the speed with which we change other forms of non-verbal communication such as gifs, stickers, emojis and memes, which are dynamic and extremely short-lived in the digital world. Replying with a gif – when even the owners of the company Giphy sounded the death knell of gifs when it said they were cringe – is also a way of presenting yourself to the digital world.

But why do we pour so much attention on linguistic decisions? It’s important to understand that when it comes to writing, the oldest generation, the Baby Boomers, are more interested in practicality. They see sending messages as “a tool to convey information (at times, emotion), never personality,” writes Angela Low in “Why Do Boomers Text the Way They Do?” – and herein lies a key difference. Our parents would never think it inappropriate to reply “Ok” when messaging, whereas if we did it, in another context, it would be interpreted as brusque or moody.

This way we have of personalising language is like trying to add a different touch to a uniform or decorating your bedroom with things you like and show who you are, so that when you open the door, it feels like your own.

Leave a comment