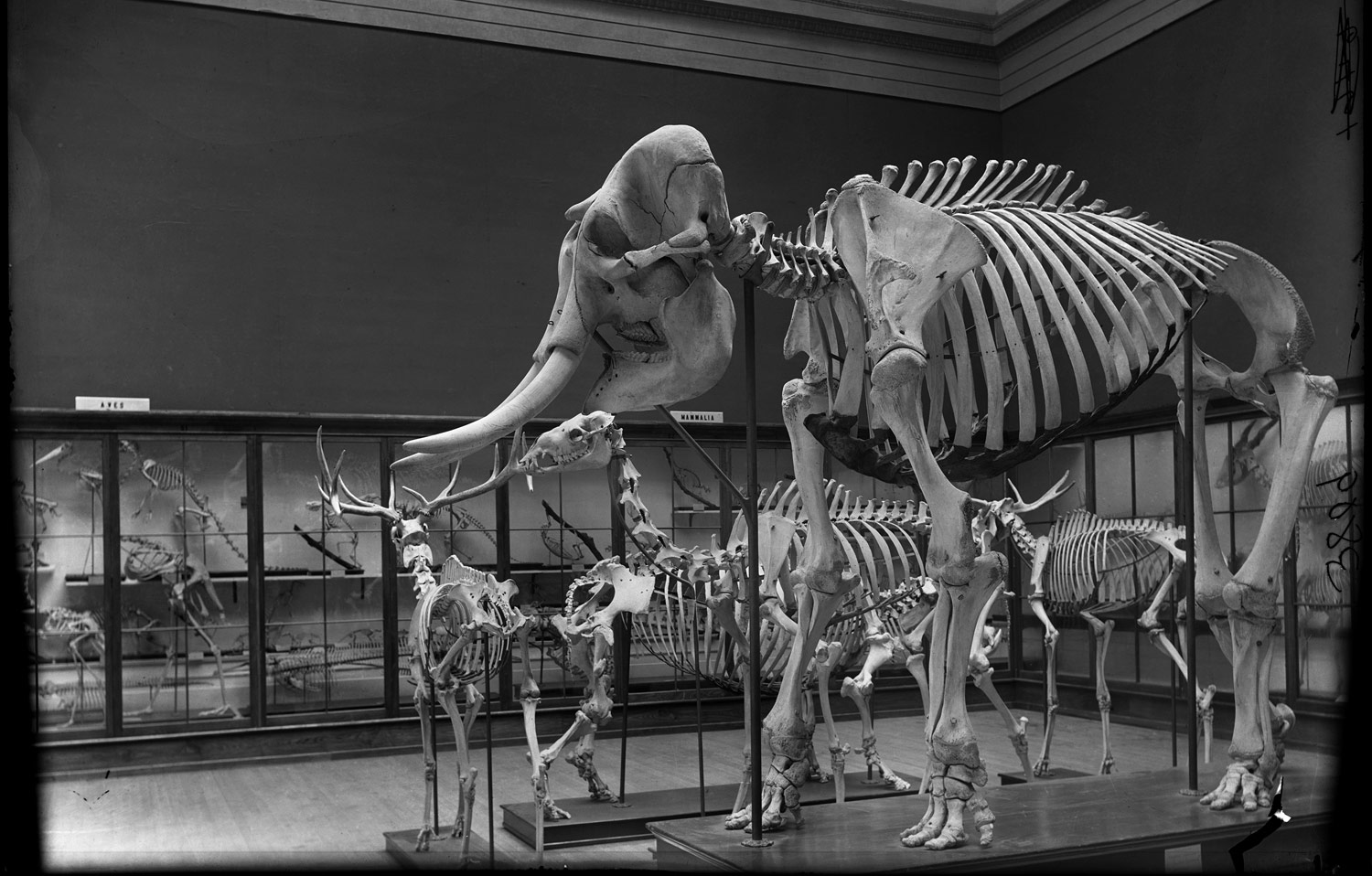

Mammoth skeletons in the Field Columbian Museum, 1898 | Field Columbian Museum | Not known copyright restrictions

Our internet-connected society is calling for more open and collaborative institutions that interact directly with citizens and tend towards a ‘digital democracy’. In spite of the resistance to change and the difficulties it entails, public institutions must adapt if they do not want their roles to be taken on by outside organisations or networks.

One of the frustrating things about debates over the future of technology is that they often rapidly devolve into a set of oppositions: either/or, this or that, good or bad, instead of trying to take in the full nuance of the implications of technological change and our relationships with technology.

Evangelists often fall into the trap of believing that new technology will bring revolutionary change in society and even in human nature. Pessimists too often predict doom-laden scenarios in which everything that we have learned or valued is undone by the impact of a new technology.

As Matt Locke explains in this piece – we are often unable to predict the future accurately because we tend to base our predictions on our experience up to the present moment, an experience which is too limited to help us make accurate predictions about what the future will bring.

The reality of the change wrought on our institutions by the Internet is complex, and in many ways unexpected. But as some of the outlines of that change are starting to emerge, it is an exciting moment to be able to chart them.

It is a commonly-held belief that the Internet will change our public institutions, tending to make them more open, transparent and collaborative.

A 2010 study by Pew Research Center found that:

A highly engaged set of respondents that included 895 technology stakeholders and critics participated in the online, opt-in survey. In this canvassing of a diverse number of experts, 72% agreed with the statement:

- “By 2020, innovative forms of online cooperation will result in significantly more efficient and responsive governments, business, non-profits, and other mainstream institutions.”

But to what extent is this really true? And how is the growing interconnectivity provided by the Internet actually affecting our institutions, their roles and their relationships with the public that they serve? The main areas in which people usually expect institutions to adapt for the internet-connected society include:

- Transparency: making a commitment to accountability; publishing details of decisions and the decision-making process.

- Porosity: breaking down boundaries between the institution and users/audience; involving the public and other stakeholders in the institution’s work.

- Openness: following open data principles and making more internal data available to the public.

- Collaboration: making a commitment to working with stakeholders/clients/audience in a truly collaborative way – co-creating work and value.

- Communication: more responsive, faster communication via email, websites, messaging services and social media.

This is partly because of the original ethos of many of the foundational services and communities that the World Wide Web has engendered and which still inspire many of its most important thinkers, advocates and resources (e.g. W3C, Mozilla, Wikimedia foundation, FLOSS, Linux, etc…)

And it is also because our experience of the Web as individual users has increasingly come to depend on and allow these kinds of collaborative and open exchanges. Via social networks, for instance, we are used to responses in real time, we are used to trusting and sharing information for the sake of crowdsourcing projects and ideas, and we are used to a certain philosophy based around bottom-up, non-hierarchical, non-commercial organisation.

When we talk about public institutions, we are used to talking about governments, public agencies, municipalities, public utilities, publicly-owned broadcasters and other civic organisations. But perhaps it would be more helpful to consider the role of institutions more broadly. Instead of associating the institution with a particular organisation, we might consider instead how the institution’s role, or the space it has traditionally occupied, is being opened up by technology. And how our expectations of what an institution is and does are shifting.

Creative Commons guiding the constributors | Wikipedia | CC BY- SA 3.0

In just the last week for instance, we have witnessed the CEO of Facebook posting criticism of the Trump administration to his social network. We have seen splinter groups of officials within several agencies (@NotAltWorld , @ALTUS_NPS , @RogueNASA, etc… ) take to Twitter to provide an alternative voice for their services when the official Twitter feed has been censored or silenced.

Social networks, as private companies aggressively harvesting and monetising their users’ data, hardly seem the obvious candidates to replace functions of the legislature or the journalistic profession. And yet we cannot deny that social media networks increasingly function as a site for political discussion and mobilisation. Whatever we think of the quality of this discussion, its potential for abuse, and the likelihood of this mobilisation leading to lasting change, social media companies are being forced to (reluctantly) consider the role they ought to play in civil society.

This process will engender a whole new set of problems related to the conflict between the profit motive and the interests of shareholders on the one hand, and, on the other, the political role that users increasingly expect social media companies to play – not just enabling users themselves to voice their opinions, but using the corporation’s power to advocate political change on behalf of its users. CEOs who are not seen to respond adroitly to this demand are quickly criticised, though whether or not users will take their business (and crucially their personal data) elsewhere remains to be seen.

At the same time, traditional public institutions may have strong motivations for becoming less transparent and less ‘porous’ even as the online community expects more from them. In an age in which leaked secrets and data have become regular occurrences, and security is growing ever more important, many will try harder than ever to preserve their own internal data and knowledge.

Especially in an environment of reduced public expenditure and increasing cynicism about the value of expertise, many bureaucracies will feel threatened and may become paranoid about the loss of their unique knowledge, leading them to guard it more closely, and preventing innovative collaboration with others or with the public to improve the efficiency of services.

Although efficiency and productivity in an age of linked data and automation may lead to reduced budgets, personnel and authority, there are incentives against digital transformation and openness which are not to be underestimated. There is also more constructive criticism based on the legitimate concern that the wisdom of the crowd may not in the end be a match for the deep subjective knowledge of experts.

Even institutions that do want to make their services and data more open face considerable practical challenges in doing so, especially where they do not have sufficient internal resources or lack the knowledge required.

Julian Assange’s original essay describing the aims of Wikileaks was an attempt to outline a cognitive theory of information-sharing within bureaucracies. It highlighted the ways in which organisations might react to leaks by trying to control information even more strictly. The potential negative effects of leaked data on governmental agencies is clearly described:

Of course leaking data in an uncontrolled way is not analogous to sharing well-structured data with the public in order to achieve common goals, but the ‘institutional mindset’ in some organisations may lead to concerns that the difference is not sufficiently clear and that openness poses a real risk.

But there are also numerous examples of imaginative co-creation and collaboration between such institutions and their stakeholders or the wider community, many inspired by the growing Commons movement and the model of peer-to-peer distribution networks. These include initiatives such as the Open Ministry in Finland which crowdsources legislation, the Bologna Citta Collaborativa project which manages collaborative initiatives between Bologna’s public authorities and local residents, and developments in ‘digital democracy’ or ‘e-democracy’ such as Pol.is, WAGL and Your Priorities.

The UK government, driven by a Cabinet Office decision to make service delivery ‘digital first’, has greatly simplified and opened up government data and services for everything from renewing a passport to finding out about tax residency and viewing statistics. data.gov.uk is a repository of government data which aims to transform the availability of publicly-held data to citizens.

Meetings with the mayor: Can Peguera and Turó de la Peira | Ajuntament de Barcelona | CC BY-ND 2.0

In Barcelona, Ada Colau’s Ajuntament has made very visible efforts to engage residents in the decision-making process on a range of issues, from transport systems to regulations on public space, but the extent to which the daily business of administration and government can be carried out through public consultation is still relatively untested.

One thing seems certain: if traditional institutions do not adapt to meet the needs of their communities, their roles will be taken over sooner or later by outside organisations, by groups or networks of individuals, or a combination of the two. And as we have seen with traditional and social media’s shifting contributions to the political process, the role of existing institutions may be taken on by the most unexpected substitutes and interpreted in the most unpredictable ways.

Leave a comment