Women’s liberation march at Washington, 1970 | Library of Congress

Are social networks a new tool for women’s empowerment? Or are they incapable of deactivating the mechanisms of inequality? As a new means for promoting communication and dialogue, social media have entered our digital lives wrapped in an attractive package -ease of use and immediacy- that leads us to optimistically consider their potential to speed up the process of women’s empowerment. But perhaps the virtual world is only a parallel reality, without any connecting vessels to the grim physical world, and neither Twitter nor Facebook are programmed to apply pressure to the age-old patriarchal structure.

In (h)adas. Mujeres que crean, programan, prosumen, teclean, Remedios Zafra writes about the emancipatory effect on women’s lives of the advent of technologies of everyday life (from washing machines to fridges, food processors and electric irons), many of which became mass consumer goods in the fifties. There’s no doubt that these machines made life much easier for that fifty percent of the population who were denied entry into all kinds of fields, so it’s hardly surprising that they also confirmed our reign precisely in the sacred domestic domain, the only space where we were allowed to rule. Which is why Zafra describes the as “hierarchical and low-tech, not productive technologies but mediators of consumption; prosumer tools designed for non-epic tasks, for tasks from the shadows (out of sight) of daily life.”

These and other advances now give women more time to spend on other tasks, such as practicing medicine, becoming a member of parliament, or writing this article, so we should acknowledge their advantages over and above their shortcomings. They also explain why we were so ready and willing to welcome the new information technologies when they landed in our homes. In 2006, when “digital democracy” began to take off (that is, when Facebook, which had been created two years earlier, opened up to everybody, eventually reaching today’s more than 350 million users), we believed that after cultivating silence and/or frugality of expression for centuries, this new modality of democracy would be our opportunity to finally conquer our fair share of spaces of communication.

A Virtual Room of Our Own

In the last few years we have gone from low-tech to high-tech, from the prison of the home to the wide-open window of a virtual room of our own, from what Sadie Plant calls ‘technogender’ to ‘cybergender’. As a silenced sector of society, we threw ourselves into taking advantage of social networks without defences, without protection. And in 2006, Time magazine seconded our desire to participate in the festival of networks on equal terms by choosing a very special figure as its “person of the year”: “you”.

This “you” encompassed all the anonymous men and women who were on the threshold of a new era in which they would play a leading role. It was a “you” without gender, and as such it included women, who, for better or worse, had already attained a room of their own (to borrow from Virginia Woolf) and who began to throw themselves into their e-mail and Twitter accounts, Google groups…. that is, a virtual room of their own. The incentive was great, and we became part of it very quickly, to the point that women are now the majority on social networking sites according to the figures released by Finances Online, which show, for example, that 76% of adult women in the United State use Facebook, compared to 66% of men.

In the world of ICTs, social networks (particularly ‘horizontal’ or contact-based networks) are certainly the ideal tool for transmitting messages and information (sometimes to the extent of going viral), and this makes them a coveted space to be conquered. And while individuals and social groups that were already empowered have simply had to adapt to the new language in order to extend their power, individuals and groups that had hitherto being silenced have seized the opportunity to reach a level of impact that is not available to them through “official” channels.

Wasn’t this the case in the so-called Arab spring uprisings, where social networks played a crucial role? Would the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia or the Tunisian Intifada have taken place if the self-immolation of a young street vendor hadn’t spread like wildfire through social media? And would the uprising in Egypt’s Tahir Square have been possible without the active involvement of Internet users? Would the Cuban blogger Yoani Sánchez be able to “broadcast” the injustices that take place in her country if she hadn’t been able connect to social networking sites thanks to a wi-fi connection in a hotel in Havana?

Aman during the 2011 Egyptian protests carrying a card saying “Facebook, #jan25, The Egyptian Social Network”. Source: Wikipedia.

Social networks, particularly Twitter, were also key to the success of the “indignados” movement in Spain, allowing 15-M Democracia Real Ya to convene 130,000 people with a few hashtags, for example, which is easier said than done. We can wonder if the civil rights movements in the US would have advanced much more quickly if somebody had recorded on their iPod the moment when Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white man on a public bus in Alabama in 1955. The video would certainly have spread like wildfire, much faster than Scarlett Johansson’s cute poses.

A New Communications Paradigm

Although some social networks have been more successful than others, the phenomenon is still growing, hot on the heels of the development of new apps. For instance, the use of Twitter skyrocketed in 2010 as a result of the arrival of smartphones on the market, and 70 million tweets are now posted every day. This means that social media are not just highly sought-after “unofficial” channels, they are also in crescendo, and this encourages women to think that they are not governed by the same laws as the outside world, and particularly to build up their hopes in regard to the impact of participating in them.

The ample evidence of the huge impact and unstoppable rise of social media leads us to consider them a means of liberation. And to see them as an enormously useful way of supporting the empowerment process that we have been pushing for decades, and even as a tool that can speed it up considerably. Will social networks become weapons against gender inequality, just as they appear to be helping to overthrow anti-democratic regimes? And if so, how real is their impact, and how much does it affect the chain of indicators that is used in the outside world?

Social networks have a proven capacity to redefine the space of interaction, and to create virtual communities. Social media create networks by interconnecting us, and this makes them an exceptional vantage point from which to draw attention to different social issues, including women’s issues. What remains to be seen is whether they will only be able to interconnect those who are already peers –like the social network BlackPlanet, created in 1999, for example– so that in the worst case they will simply end up generating a great community of feminists that will remain separate from non-feminists.

We also have to take into account the fact that networks are no longer just spaces where people can share ideas to make the world better, or factories of idyllic love: they also have great advertising potential, and advertising is still a tremendously male-centred world. This is why Boyd and Ellison have described social networking sites as “web-based services” or, in other words, as an extension of non-virtual reality rather than a new paradigm. As Judy Wajcman says in Technofeminism, given that “the relationship between technoscience and society is currently being subjected to profound and urgent questioning”, it seems reasonable that the much more recent phenomenon of digital technology should bring about utopian and dystopian visions. In this sense, we move between “utopian optimism and pessimistic fatalism” (Wajcman again).

Networked Feminism

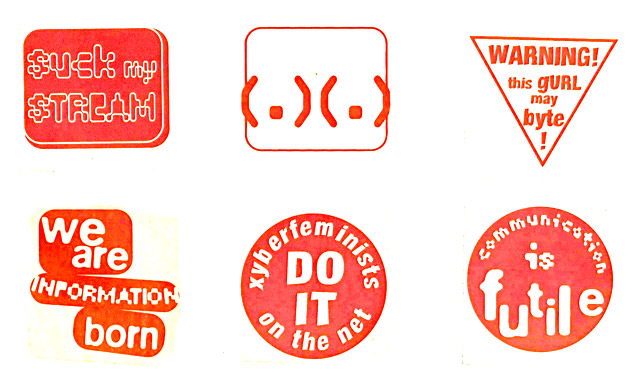

The first Cyberfeminist Manifesto was presented by the group VNS Matrix in the mid-nineties in Adelaide, Australia, and the first Cyberfeminist International was held at Documenta X in Kassel. Although the cyberfeminist movement may be somewhat wild or constantly in the process of being redefined, its members continue to emphatically claim that gender inequality does not exist in cyberspace, and that the Internet has the capacity to transform conventional gender roles. Could this be wishful thinking, particularly among younger women who also think that the glass ceiling is a thing of the past in the non-virtual world too?

Stickers made for the 1st Cyberfeminist International. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

In the academic world, gender studies departments are already carrying out research into the creation and transmission of feminist discourses in the new communication environment (particularly social networking sites). Most of these studies find that the horizon of expectations of online feminism is no different to that of other types of feminism, but that it takes advantage of the new possibilities to carry out virtual actions and coordinate strategies. Unfortunately, in spite of the optimism of early cyberfeminists, it seems like there is still a long way to go before the Internet gets rid of sexual difference (Judith Butler talks about “undoing gender”). To say nothing of the fact that if sexual difference is ever erased, this change would be an excuse to carry out a kind of amnesty: to erase the past, forget the centuries of shame, and throw the key of domination into the cybernetic ocean.

For the time being, it is true that gender anonymity is possible on the Internet, that it allows us to be free of the tyranny of the body, and that this leads to a blurring of the boundaries between the sexes. “I’d rather be a cyborg than a goddess,” wrote Donna J. Haraway, arguing that we who live in a postmodern world are becoming cyborgs: “creatures in a post-gender world,” as she says in Science, Cyborgs and Women. But we are yet to see whether women’s participation on the Internet, on social networking sites, will substantially affect our hitherto silenced identities, and give us a greater presence as prescribers: will social media be the amplifier that we women have been seeking in order to find our place in this new reality?

In order for this to be so, social networks must be able to pro-actively contribute to the construction of this reality, and not just passively reflect what takes place outside of them. In some sense, they must have the capacity to establish a new precedent, to “feminise the world that flows through them.” In other words, the question remains: Have women been invited to the social media party, or are we just gatecrashers? Are we valued or put up with? And most importantly, will we be able to convey transformative messages through them? And if we are already doing so, how are the results of this empowerment being monitored and measured?

We would like to think of social media as a shared space that works according that what Saskia Sassen has called “the logic of incorporation”. We want them to become a kind of fabric woven out of open networks that can incorporate new forms of knowledge that challenge those imposed by mainstream culture. To paraphrase Sassen again and transfer her ideas to the field of genre, we want networks that are able to dribble patriarchal distortion and foster new mechanisms, new systems of fair distribution. Having confirmed the usefulness of networks as communication channels (see for example The Freedom Train that recently used social media to organise a protest against the Spanish government’s proposed abortion legislation), we are yet to confirm their use as an instrument of transformation.

Do social networks really boost the visibility of women’s work? Or do they trap women in a new type of invisibility, like “kitchen technology” did? These questions are not intended to be pessimistic, only to highlight the ambivalence of social media and of their possible effects. Time will tell whether they are useful for dissent or for affirmation. Meanwhile, rather than talking about ‘(h)adas’ (a play on words between the Spanish word for Fairy and Ada), we should focus on being ‘(en)redadas’ (in a net, tangled together), in the sense of being connected and caught up, rather than hooked. This does not change the fact that, every day, millions of women all over the planet, in precarious phone centres or on new-generation laptops, continue to share their hopeful voices on Twitter, Tuenti or Facebook, with the certainty that somebody on the other side is listening.

Bibliography

Donna J. Haraway: Simians, Cyborgs and Women. The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991).

Sadie Plant: Zeroes + Ones: Digital Women and the New Technoculture (New York: Doubleday, 1997).

Judy Wajcman: TechnoFeminism (Oxford: Polity Press, 2004).

Remedios Zafra: Netianas. N(h)hacer mujer en Internet (Madrid: Lengua de Trapo, 2005).

Un cuarto propio conectado. (Ciber) Espacio y (auto)gestión del yo (Madrid: Fórcola, 2010).

(h)adas. Mujeres que crean, programan, prosumen, teclean (Madrid: Páginas de Espuma, 2013).

Leave a comment