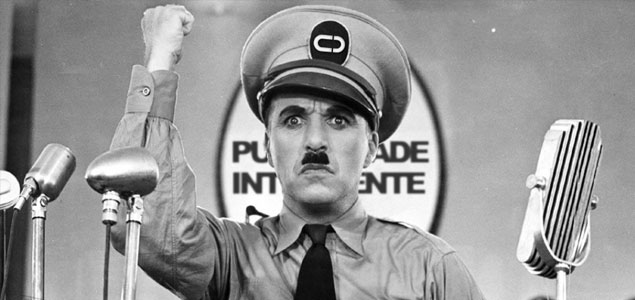

The Great Dictator (Charles Chaplin, 1940).

In the second episode of the fourth season of the series Breaking Bad, two of Jesse’s friends, high on meth, start discussing videogames. Comparing the virtues of different games, they end up talking about one where the player is faced with Nazi zombies: “Nazi zombies don’t want to eat you just ‘cause they’re craving the protein. They do it ‘cause they hate Americans, man. They’re the Talibans of the zombie world.” Although the character is high on drugs, the logic of his discourse is not too far removed from popular logic. Because in the collective imaginary, the words “Nazi” and “Taliban” have gradually disassociated themselves from their historical specificity and, therefore, from their proper meaning, to end up both meaning something similar. And I say “something” because I am interested in the lack of specification of the indefinite pronoun. Barbarians, infidels, savages, Jews, Moors, Frenchmen, Cossacks, Spaniards, Nazis, Charlie, Talibans: for centuries these and other similar words have been used to designate othernesses that were more or less similar to the eyes of whoever used them. Because language, which always has historical roots, tends towards a change of context, towards perversion and towards more or less unconscious fictions. An original reference point exists, more or less close to a (historical) reality; but between the first fictionalisation and that origin, a distance opens up that increases as time passes and, with it, the work gradually ramifies, diversifying and multiplying itself in readings and re-writings. If it has become – regrettably – commonplace to say that the Israeli policies towards the Palestinians are Nazi, it is because Nazi has become emancipated from Nazism. Carnivals form part of that slow mechanism of dissociation. While the miniaturisation of wars through little lead soldiers is not subjected to any moral judgement, meaning that shortly after the end of the Civil War or the Second World War, the corresponding miniscule armies started to be sold, their representation in the form of fancy dress must still obtain social approval. For that reason Britain’s Prince Harry and magnate Bernie Ecclestone were reprehended for costumes they wore. The fact that they were fictions (i.e. fancy dress) didn’t exonerate them from having trivialised something taboo. We have not yet dissociated the swastika from the massacres.

The distance that separates the historical event from its fictionalised version constitutes the first of the numerous screens that filter the increasingly distant reception of what was reality. En 1940, Charles Chaplin parodied Adolf Hitler in real time. With The Great Dictator he continued with a process that had already begun in caricatures and cartoon strips on both sides of the ocean and to which many other films would contribute during the course of the Second World War: the conversion of the German genocidal leader into a fictional character. On the first front cover of Captain America, which appeared in March 1941, the superhero was punching Hitler. Nearly half a century later, in The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, Michael Chabon made the Escapist, the superhero created by the main characters, also enter the comic strips arena by punching Hitler from the very first front cover. A little later, Quentin Tarantino premiered Unglorious bastards, a film in which American Jews of the 1940s are in reality as hardened and vengeful as the Israeli Jews of the 1950s or 1960s, where Hitler appears for the umpteenth time. A version closer to that of Chaplin than to that of Downfall. By that time, the Nazis and their descendants had become a narrative resource, archetypes of evil, backdrops and reasons for serious exploration (Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom, by Pasolini) or blistering comedy (Mein Führer: The Really Truest Truth about Adolf Hitler, by Dani Levy). They became something that maintains a very vague relationship with the terrible original source. Indiana Jones against the Nazis. Tom Strong against the Nazis. The porno film that Hitler filmed (inDesolation Jones, the comic book by Warren Ellis). Captain Nazi, rival to Captain Marvel. Red Skull, ex-Nazi general and Hitler’s confidante. Nazis as secondary Fringe characters. As if the plan to clone Hitler, which a fictional character named Josef Mengele tried to carry out in The Boys from Brazil, had been successful, but in the fictional plane. One cell of Hitler in each fictional character that is inspired, to minimum or maximum effect, by Nazism. Nazi vampires, Nazi Amazons, sado-masochist millionaires dressed as Nazis, living Nazis and dead Nazis: Nazism as a Nazi army of viral icons infiltrated into all the twists and turns of Fiction, from sexual fantasies of mansions and dungeons to ultra-violent videogames, and not forgetting comedies featuring Nazi zombies such as Dead Snow.

In the prologue to the US edition of A Tomb for Boris Davidovich, by Danilo Kiš, Joseph Brodsky writes: “Sooner or later, every revolt ends up in a work of fiction”. This means that revolution needs testimony and magnification, chronicle and narrative. The destination of Reality is not only to be narrated in a historical key, but also to be transformed into a story, novel, comic, film, television series, videogame, Fiction. Journalism, history, documentalism, literature and cinema alike make use of texts, veils and screens to tackle the representation, direct or distorted, of what happened. At certain moments in human history, narrative artefacts existed capable of giving an agreed or predominant meaning to a historical experience. Just three years after the end of the Second World War, with all its complexity and its infinity of inter-crossing discourses, Norman Mailer’s book The Naked and the Dead was published, not only as the great novel on the Second World War, but also as one of the great war novels of history. Ten years after 9-11, no work on the attacks has met with a similar consensus. In our country, we often cite Soldados de Salamina as the start of interest in the last decade in cultural products linked with the Civil War and the Franco regime, but the truth is that for over seventy years there have been novels and comics published, and films premiered, that deal, in one way or another, with those conflicts. While it may be excessive having to go back to 1939 films such as Sierra de Teruel or Frente de Madrid or to 1970s comics such as Eloy to understand how the representation of the Civil War is configured in our consciences, I do think it is pertinent to think about the mass of texts including the novel by Javier Cercas, and the cinema adaptation produced by David Trueba. In other words, to think about the screen of screens or network of figurations in which the central element of Spanish history is represented in the consciences of the Spanish people.

Immediately before Soldados de Salamina, there was another book which also became a hit film and which tackled the struggle: Butterfly (by Manuel Rivas and José Luis Cuerda, respectively). A little before or a little afterwards, other realist and fantastic films were released such as Land and Freedom, Libertarias, El laberinto del fauno, Las 13 rosas and El espinazo del diablo. But these novels and films are no more than a part of the cultural products of 20th-century Spanish history that have gradually become rooted in our brains. In recent years, while José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero’s government promoted the Law on Historical Memory, the interpretations, versions and fictionalisations of different people were gradually being converted into nodes of the representational spider’s web that we call “the Civil War”. Vaguely, because often entering under that label are what we call “The Republic”, part of “the Franco years” and our perspective anchored in the “Post-Transition” period. Over the last decade, for example, it is difficult to find a pop album that doesn’t contain at least one song on the subject. Or a television series that, judging by the audience ratings of Cuéntame, has not dealt with the issues in one way or another, until we reach 14 de abril. La República and Temps de silenci. In Psicodelia y ready made (Adriana Hidalgo, 2010), German critic Diedrich Diederichsen wrote regarding May of ’68: “Its evocation serves, like all evocations of a generational community, for participants to assure each other in a flattering way that they were present at something major. Television documentaries such as Nuestros años sesenta continue to inform, decades later, about how long exactly it took the sexual revolution to reach the small city of Dinkesbühl or when the Beat movement disembarked in Dresden. It could be said that all these constructions help real people who lack any power to have the feeling that they did not live completely detached from the historical reality.” The same mechanism has been in action, in the Spanish case, during the last decade and a half. Screens have gradually convinced us that that history was our history, with a power of conviction much greater than the anecdotes and traumas recounted to us by our grandparents.

In the last year of the 20th century, Peter Sloterdijk began a famous controversy with the paper that would later become Rules for the Human Zoo, whose thesis was: “modern societies can produce their political and cultural synthesis only marginally through literary, letter-writing, humanistic media”. There is no doubt that the epical and the lyrical, in all their traditional artistic manifestations (poetry, theatre, painting, novels, opera and film), ceased to have the influential capacity that converts a synthesis into a central discourse. The Screen is global because it is the sum of all cinema screens, television screens, computer monitors, mobile telephones, medical apparatus screens and GPS screens. Of all the pixelated representations that surround us and constitute us. But at the opposite pole to that of the global, we do not find, as is usually said, the local. Rather, we find the individual. The global screen only exists in individual consciences. And in these, the textual and the audiovisual coexist without divisions or easy discernment. It could be said that literature left its central place to cinema and that cinema was displaced by television, and that television has been ousted, or simply enhanced, by the Internet, at the same time that videogames were becoming a very powerful industry and one partly essential to the universal imaginary; but in the human brain, where the factual and the fictional are in perpetual contest, there is no centrality possible, above all because literature, painting and cinema continue to be the models which we read and watch. Representations are constantly amalgamated, into translations that partially forget the source language, that distort and adapt and impoverish their sources just as all discourses regarding the real do, whether documentary or fictional. Thus in our age it is difficult – if not impossible – for a synthesis capable of critical consensus to be in a work (whether this be a novel, an essay, a film, an artistic piece, a television series, a comic book or a videogame). The synthesis can only come later, through the discussion of works and products that are not conceived as an archipelago, but that the critic or reader can and must relate to each other. With the global screen we have access to the pieces of the puzzle, but only in the individual conscience can they fit together and find a meaning. Infinitely fragmented into often contradictory figurations, History waits for each person to reconstruct their archipelago. And to interpret it once more.

Leave a comment