Taula del Departament de l’Armada d’Estats Units. 1922 | Library of Congress | Domin públic

The instability that crises entail steps up the struggle to define the imaginary of the world to come. Right now, predictions for the future not only help us deal with uncertainty, they also establish the frameworks of what is desirable, what is expected and what is possible. Graphics, then, show themselves to be powerful weapons for the construction of tomorrow.

“So if epidemiological statistical models don’t give us certainty—and asking them to do so would be a big mistake—what good are they? Epidemiology Statistics gives us something more important: agency to identify and calibrate our actions with the goal of shaping our future. We can do this by pruning catastrophic branches of a tree of possibilities that lies before us.”

Zeynep Tufekci [1]

We are part of a process of interruption and re-stabilization of the social and its institutions: the market, education, the State and other supra-state organizations. Confinement has caused a disturbance in the social experience of becoming. The virus has hacked the software of the real, exposing some of the infrastructures that support and (re)produce it. In this paralysis, the structures of social change—especially those of techno-scientific enterprise, its representations and myths—become more intelligible.

The suspension of the illusion of social stability (commonly known as normality) opens the door to endless new questions. Will the time come when we can coexist with the virus in a non-conflictive way? What about my summer holidays? Will we go to mega- concerts again? Will I get my job back? What will be the consequences of the economic crisis? Will control measures become embedded in a new social order? Are we witnessing the end of neoliberalism? Will it strengthen the welfare state? Will we be able, finally, to dramatically reduce CO2 emissions?

The production of the time to come

Futures are socially constructed objects that are updated very slowly. Their cultural body feeds on the inertias that drive these institutions that are mutating due to COVID-19.

Futures are conflict zones where social movements, research centres, professional societies, and the entertainment and information industry converge. They are inhabited by desires and fears, both individual and collective, that are interwoven with different imaginaries (and lacks of imagination), and their source code reproduces ways of living and relating.

Futures are representations of the time to come that compete by updating themselves in the present to complete themselves both materially and culturally. Each one of them involves more or less specific conceptions of what it means to be human, nature, development, justice, wealth and life.

With the virus, the social body and mind are mutating. Habits that previously coexisted now intensify and fade. The experience of the collapse, already made explicit in different areas of our planet, is gaining ground to the delirium of the global North. It has become undeniable that we find ourselves in what, in 2011, the philosopher Lauren Berlant called a “state of impasse”. We are living at a “moment where existing social imaginaries and practices no longer produce the outcomes they once did, but no new imaginaries or practices have yet been created”.[2]

The state of emergency and physical, economic, psychological and institutional uncertainty strains this state of impasse to the point of unsustainability. And then the social body needs to reorganize itself to construct a new stability.

Just as, at other times of crisis, the reorganization process opens portals to possible new developments that compete with other, more hegemonic social imaginaries, here once again the tensions between what is and what could be make themselves felt.

Wait, fiction, data

Expectations can be defined as the state of waiting, of looking forwards (from the Latin, EXSPECTATIO, ‘anticipation’; EXSPECTARE, ‘looking outwards’). They can also be understood as a thing that does things, something that can be identified and more or less analysed, as something that is affected and that affects the world.

On this point, Jens Beckert [3] explains how expectations play a fundamental role in capitalism—an economic system constantly oriented towards an open, unpredictable future. When individuals and organizations speculate—that is, invest their capital with the aim of multiplying it—they do so using calculations of probability that do not extinguish the risk of losing. Here, in everlasting risk, in this predictive vacuum, expectations—entities that are fictitious by nature—function as a lubricant to the decision-making process at the time of investment.

This moment of delirium is an infrastructural mechanism in the dynamism of the capitalist system, but not only in the sphere of the market (especially the financial one). The production of subjectivity in the consumer economy is intimately linked to archetypes and ways of life presented as desirable.

The management of expectations is key in the production, modulation [4] and cancellation of possibilities of social change, and, accordingly, the action of predicting has a powerful agency. This way of invoking the future to reorient the decisions of the present has atavistic and mystical roots that become entangled with technical operations to unfold in more or less industrial practices. Tarot, military strategy, data analytics and strategic foresight develop their economic activity by feeling the future, to help perpetuate or change certain ways of acting and organizational forms.

The necessary confinement has short-circuited socioeconomic expectations and the futures mapped out by the various techniques of prediction and anticipation. This void can be interpreted as one of the strategic territories where the battle is fought to define the imaginary of the world to come, and although this is nothing new—it exists at every moment and is exploited abundantly in electoral processes—the pandemic intensifies and disperses this abstract space to be conquered.

The vastness of the scope of the possible should be delimited so it can be comprehended, activated and potentially instrumentalized. Here, the representations of predictive calculations work like an astrolabe: they make infinity intelligible and, in the context of the pandemic, they help frame the understanding of what we should do and expect.

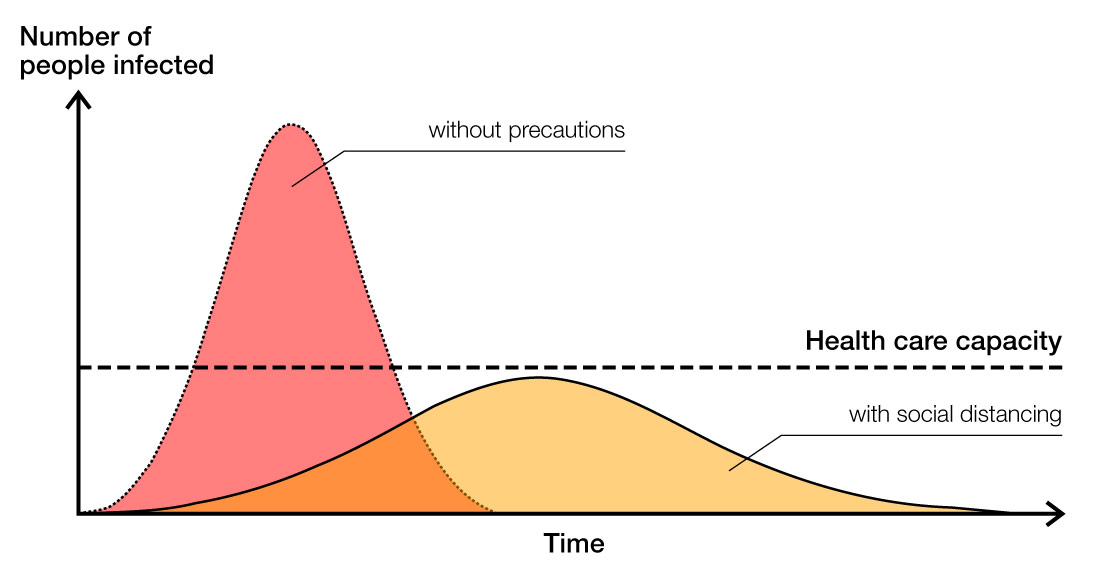

COVID-19 health care limit | Johannes Kalliauer, Wikimedia Commons | CC BY-SA

The graphs that help us deal with uncertainty have activated mechanistic models, purely statistical models, and machine learning models, mathematical functions, and more or less incomplete data packages. They have served to examine the possible evolutions of the virus in the individual and the social body in relation to the resilience of health systems wounded by austerity policies, and to project—and reassure—the fluctuations of financial markets with delusions of monopoly, unemployment rates and the recovery of economic activity, among others.

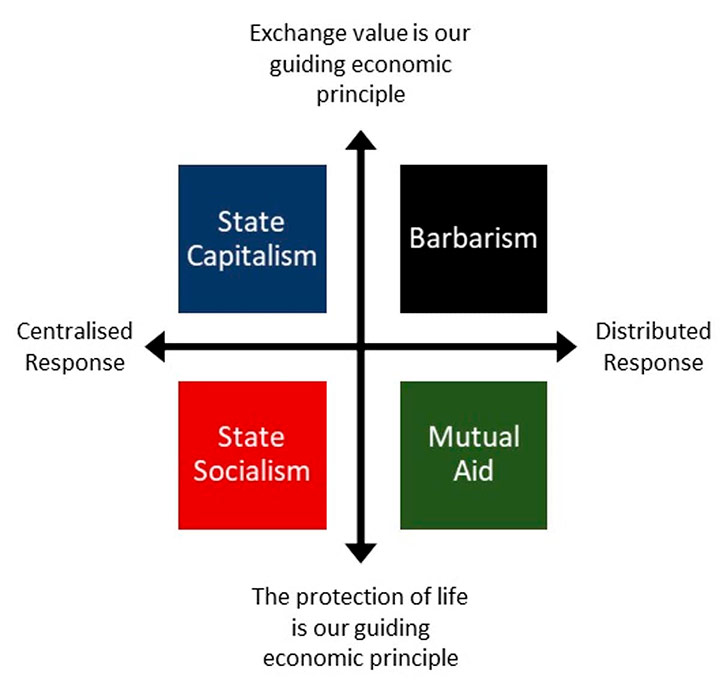

Beyond quantitative surveys, future post-COVID scenarios have also been constructed, which vary in each country depending on the strength of the welfare state, the (in)capacity for cooperation of our governments in facing the pandemic, the digitization and casualization of the labour market, and laboratories’ effectiveness in synthesizing The Vaccine.

Diagram summarising four possible scenarios proposed by Simon Mair, Research Fellow in Ecological Economics, Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity, University of Surrey. | © Simon Mair

These scenarios not only articulate the negotiation of governmental and corporate emergency committees in virtual meetings of varying degrees of vulnerability to cyberespionage. They are ways of explaining of high performative power: as artefacts cloaked in a legitimating language (that of mathematics and statistics), they translate knowledge with different levels of scientific rigour that affect the management of horizons of possibilities.

Graphs, especially in this interruption of some fundamental social inertias, tell (limit, stimulate) what is more or less expectable. They become objects capable of modulating imaginary and social expectations according to what the different actors and their prediction tools can and want to consider in their narrative of what is to come.

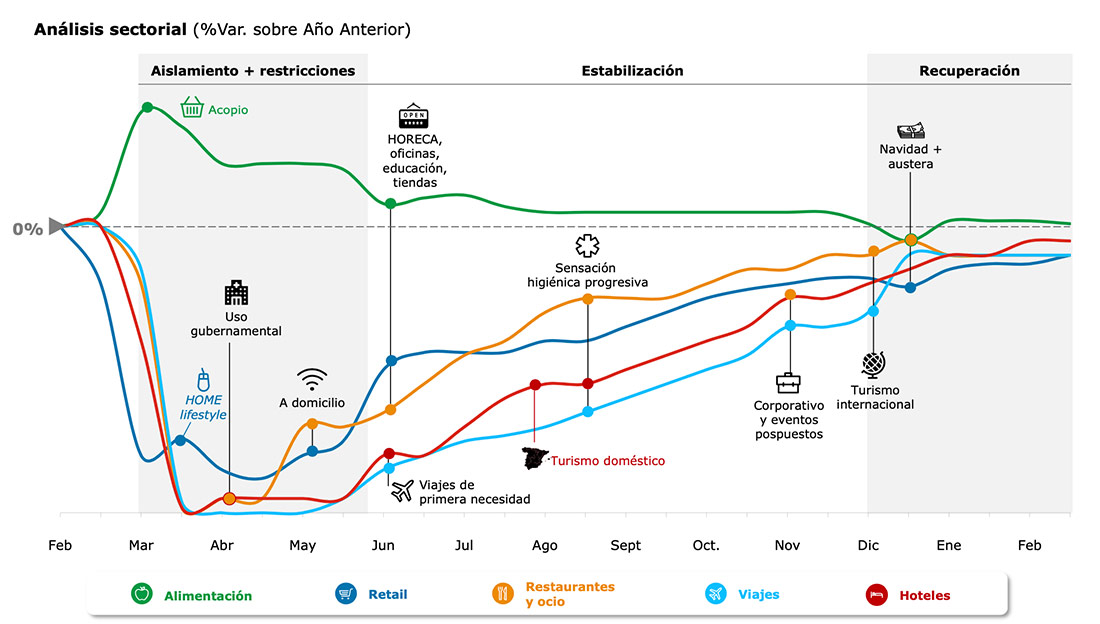

Deloitte is a big consulting firm whose future projections contribute to the decision-making of states and large companies, with the power this involves. | © Deloitte Consulting S. L. U.

It is precisely due to this ability to consolidate the visions of what is imaginable, unimaginable and desirable—and the effect they have on our ability to decide and influence the material plane—that the representations of predictive models are de facto semiotic weapons deployed in negotiations to build, in this moment of parenthesis, the stabilization of a social order that is emerging right now.

We can read graphs as Zeynep Tufekci suggests: as a representation—in all cases partial—of reality and as a guide to “agency to identify and calibrate our actions with the goal of shaping our future”. But we must not forget that, as artefacts that invoke futures, they are also non-human political actors that are involved in the management of power and, therefore, co-produce the realities to come.

Collectives such as Pirate.Care have understood very well how to use them to summon up other worlds:

![This graph by Pirate.Care expresses its intentions: “We want to claim that ‘Flatten the Curve’ is not enough. Not only do we want to keep the spread of the contagion within the limits of health care system’s capacity, but […] the social crisis resulting from the response to and the aftermath of the pandemic will require a re-focusing of societies on modalities and capacities of care.”](https://lab.cccb.org/wp-content/uploads/care_curve_1100.jpg)

This graph by Pirate.Care expresses its intentions: “We want to claim that ‘Flatten the Curve’ is not enough. Not only do we want to keep the spread of the contagion within the limits of health care system’s capacity, but […] the social crisis resulting from the response to and the aftermath of the pandemic will require a re-focusing of societies on modalities and capacities of care.” | CC BY-SA Pirate.Care

[1] Tufekci, Zeynep (2020). Don’t Believe the COVID-19 Models, The Atlantic.

[2] Berlant, Lauren. (2011) Cruel Optimism. London: Duke University Press.

[3] Beckert, J. (2014). “Capitalist Dynamics: Fictional Expectations and the Openness of the Future.” https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2463995

[4] A more appropriate word here may be nudge, deriving from behavioural economics and referring to positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as a way of influencing behaviour and decision-making of groups and individuals. For more information, see Abdukadirov, S. (Ed.). (2016). Nudge Theory in Action: Behavioral Design in Policy and Markets. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Leave a comment