Fragment of Phrenology Diagrams fromVaught’s Practical Character Reader (1902). Source: The Public Domain Review.

The ‘smart city’ –that great contemporary promise that would supposedly resolve the problems of the city– has a history of contradictions, which has ended up generating a new term that is heir to the concepts rooted in the knowledge society: SmartCitizens. Acknowledging this expression entails accepting that there is a need to rethink the effects of the exclusively technological solutions that were behind the initial smart city proposals. As such, the SmartCitizens concept encompasses initiatives that arise from collective intelligence and point the way to the transformation of the socio-economic structure of our cities, based on the capacity for connectivity, for sharing knowledge, and for being proactive with our environment.

Smart cities here, smart cities there, smart cities everywhere. Over the past few years there has been a smart city boom, to the extent that it seems that all cities have suddenly become ‘smart’[1] overnight. The exponential growth of the term has eclipsed other earlier, conceptualisations that were more comprehensive, such as the “sustainable city”[2], or that more adequately respond to the network era and to the new socio-economic relations stemming from it, such as the “knowledge city”[3]. While this terminological overexposure became deeply embedded in professional and institutional forums, in citizens themselves it simply generated an “enormous indifference”, as the president of the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces (FEMP) and Mayor of Santander, Iñigo de la Serna, recently admitted. This seems to be a clear indicator of the how remote these ‘smart cities’ are from their inhabitants.

If we are to understand this disruptive reality, we need to question the causes and consequences of the smart city phenomenon, as a springboard from which to start to build (or to reinstate) a conceptual urban framework that genuinely responds to the needs of citizens and is geared towards the effective, comprehensive improvement of the urban habitat.

Much ado about nothing

Even though the current information society was behind the emergence of the ‘smart cities’ concept, it wasn’t until the big technology corporations (IBM, CISCO, Siemens, etc.) began to take an interest in it (and to apply their marketing strategies to it) that the term began to forge its hegemony[4]. And so it was that, in 2010, numerous prestigious international media outlets (Time, The Guardian, The Times, Financial Times, etc.) began to report on this new wave of smart cities, dedicating articles, special issues, and even entire sections to the subject. At the same time, organisations all over the world began to programme a myriad of events and congresses around the topic, monopolising and influencing professional and institutional agendas. As a result, smart cities have become the main focus of the urban debate.

But instead of shedding light on how smart cities make it possible to move forward in relation to earlier theoretical underpinnings, this whole visibilisation campaign simply generated confusion and mistrust. The fact is that this initial discourse only addressed the implementation of new technologies in our cities, and failed to show how the techno-smart city utopia would improve quality of life, or how it could be of benefit to citizens. As such, the technophile justifications pushed by the multinationals simply –but not openly– disregarded internationally accepted premises[5], and ignored the fact that technology for it’s own sake goes against the principles of sustainability and contributes little towards the construction of the knowledge society, other than generating some of its infrastructure.

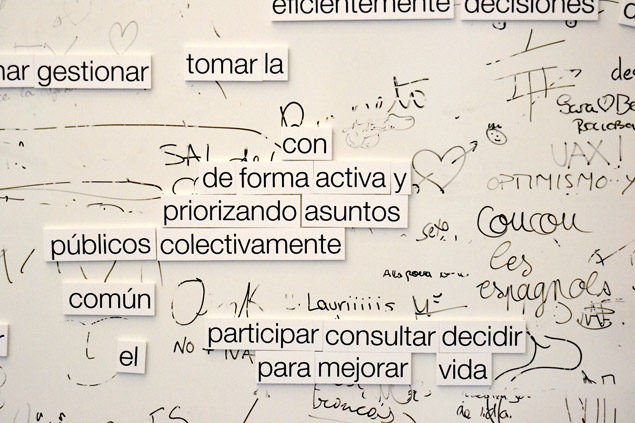

Exhivition«Smartcitizens» in Madrid. Source: SmartCitizensCC.

Nonetheless, we can now say that smart cities have recently begun to rethink their exclusively technological orientation. For instance, it is now widely acknowledged that the usefulness of smart grids is limited unless they are formulated to include citizens. Which means that it is pointless to make efforts along these lines in a context such as Spain, where the government has decided to penalise the self-consumption of electricity. In any case, this citizen-centred approach is also proving controversial because the majority of service providers simply see citizens as potential clients of the services that they can offer in smart cities. If we think of the different stages of generating, managing and using information, we see that even the most favourable cases aim to exclude citizens from the management stage, which is the key element of the business model that the big corporations are backing.

This approach again weakens the potential envisaged in the knowledge society and the open and distributed logic of the network era, generating a hierarchical, closed structure by positioning citizens as users and consumers rather than active collaborators in the transformation of their environment.

Opening up the smart city to citizens

Predictably, this take-over of smart cities proved controversial, and led to the demand for a new term that comes from the same root but is geared towards providing a necessary counterpoint to the corporatist logic. This is where the ‘SmartCitizens’ concept comes in: a new urban subject that is penetrating deep into the smart city vortex, empowering active citizens as a key element of the knowledge society, and as the backbone that runs through new urban policies.

The SmartCitizen idea reflects that fact that when we talk about smart cities and smart citizens we are talking about more than just optimising the control, use, and efficiency of infrastructures. Smart cities are also about democratising information at all scales and in all its forms (open data, open city, open government, etc.), about the knowledge and active participation of citizens. Because these two aspects, together, will make it possible to improve our habitat and our quality of life.

Against this backdrop, the notion of SmartCitizens that is starting to take hold is that which places citizens at the centre of discussions around smart cities, and defends the principle according to which you can’t have smart cities without smart citizens. In the face of the exclusive logic imposed by economic powers, networked smart citizens are generating new practices and new imaginaries that work together for a (much-needed) rethink of the smart city. The rationale behind this reformulation needs to be cooperation among the various actors that come into play (civil society, public administration, scientific and academic entities, economic agents, etc.). And its symbol of identity must be the sharing of knowledge. And this is precisely were the idea of SmartCitizens intersects with that of the free software movement: sharing and working together to improve the efficiency of processes, unleashing the power of collective intelligence in order to reach optimal solutions.

Open code smart cities

It is true that the means that now allow us to share valuable information among the many different actors and sectors of our society –and as such to transform ourselves into smart, active, participating citizens– lay the groundwork for the development of an urban model that is more democratic, more equitable, more sustainable and more comprehensive. But the efforts required to turn this opportunity into reality are still at a very early stage, and, generally speaking, the spheres of power have no interest in making this effort, when they don’t actually hinder it. This, however, does not mean that smart citizens, along with a new redefinition of smart cities, cannot be promoted from other spheres.

Exhivition«Smartcitizens» in Madrid. Fuente: SmartCitizensCC.

Taking advantage of the possibilities of the Internet, citizen intelligence is springing forth in initiatives organised by technological innovators who equip citizens to access information, make decisions, and work collectively. Free software is actually a sure-fire source of tools, apps and technological solutions to support this citizen empowerment, so much so that it is already possible to find all types of open source technology throughout the entire smart city value chain[6]: from the Internet of things (sensors, hardware, software, RFID technology, etc.), to Big Data (complex data storage and processing on a mass scale), and all kinds of applications[7].

But moving beyond this highly technical approach to smart cities and ultra-connected societies, the SmartCitizen concept also defends the need to overhaul the way we conceptualise city-building technology. And in this case the yardstick is not the sophistication of the technology that generates it, but its capacity to generate community, forge networks, and set up knowledge transfer channels that favour social autonomy. This again breaks the dominant discourse, because from this perspective, an urban market garden is at least as smart as a smartphone.

In short, the idea behind the SmartCitizens concept is that the most effective urban technology is that which emerges from collective intelligence, helps to generate community, opens up channels for citizen appropriation, can be reproduced, is efficient, and is geared towards meeting the real needs of civil society. SmartCitizens reveal that the future of cities is in our hands; in the hands of an intelligent, collaborative society.

Paisaje Transversal is an office that promotes, coordinates, designs and provides consultancy services on innovative urban analysis and transformation processes, from participation to ecology and creativity, always tailored to the local reality: http://www.paisajetransversal.com/

Since 2007, Paisaje Transversal also operates as a platform for research and theory around the topics of city and territory, which provides theoretical support to the office. Its most visible side is the blog www.paisajetransversal.org, which has been one of the world’s most influential Spanish-language architecture blogs for over four years.

[1] For example, the Red de Ciudaded Inteligentes (Intelligent Cities Network), which was created in Spain in 2012 as an alliance of half a dozen City Councils, now has 41 city-members and this number is still growing steadily.

[2] To find out more about the comprehensive nature of the “sustainable city” urban model, we recommend the theoretical work carried out by the Agencia de Ecologia Urbana: http://bcnecologia.net/en/conceptual-model/model-sustainable-city

[3] “(The knowledge city) Is a geographical area in which –according to a plan and an overall strategy adopted jointly by society and the government– the actors involved have the common goal of building an economy based on the development of knowledge.” José Natividad González Parás.

[4] For more on smart cities, we recommend the following compilation of articles (in Spanish) by Manu Fernández (@manufernandez): http://es.scribd.com/doc/61950985/Smart-City-Tecnologias-emergentes-para-el-funcionamiento-urbano

[5] The Hype Cycle for Smart City Technologies and Solutions research report published by Gartner Inc. in 2012 defined a smart city as “an urbanized area where multiple public and private sectors cooperate to achieve sustainable outcomes through the analysis of contextual information exchanged between themselves. (…) The interaction between sector-specific and intra-sector information flows results in more resource-efficient cities that enable more sustainable citizen services and more knowledge transfer between sectors.”

[6] The smart city technological value chain was analysed by Telefónica Foundation, among others, in its report Smart Cities: Un primer paso hacia la Internet de las cosas. Available at: www.fundacion.telefonica.com/es/que_hacemos/media/publicaciones/SMART_CITIES.pdf

[7] In Spain, the CENATIC National Open Source Software Observatory offers an interesting compilation of open source technology in relation to smart cities in the article “Open Smart Cities I: La Internet de las Cosas de Código Abierto”.

Leave a comment