Blind athletes at Overbrook. Philadelphia, 1911 | Library of Congress | Public Domain

Organising ourselves has been fundamental for surviving and structuring life in common, changing according to the time and the place. In his book Reinventing Organizations, Frederic Laloux explains the history of organisations according to how power relations are distributed and the role that is played by individual conscience, establishing an evolutionary scale where each stage is associated with a colour. At the top we find the turquoise or teal organisations: those that function as organised ecosystems in a network of inter-dependent nodes, the paradigm of decentralised leadership and where decisions are made in a distributed way. We analyse the characteristics of these organisations and present examples from the public sector that illustrate how making this change is possible.

From shamanic tribes to the social movements we set up today via hashtag, behind any version of a social organisation there exists a particular logic that accompanies the dance between individuality and collective behaviour. Organising ourselves has been fundamental for survival and for articulating life in common, changing according to the time and the place. How organisations are formed and governed is not at all universal or spontaneous, but rather it reflects needs, values and fears. And if there is something that responds to extreme rationalisation and fear of uncertainty, that is the public administrations.

When Asterix and Obelix enter The Place That Sends You Mad (The 12 Tasks of Asterix) they discover an absurd number of windows. We will likely laugh out of complicity, having ourselves suffered that amber, rigid and exasperating bureaucracy in the first person. The relationship between carrying out a simple formality and feeling that we are time-travelling into the past is becoming increasingly pronounced. If life has become liquid and fluid Bauman-style, the administrations necessarily have to make the change, from iron-like rigidity to the flexible firmness of bamboo. It is necessary to break those “iron cages”, using the words of Max Weber.

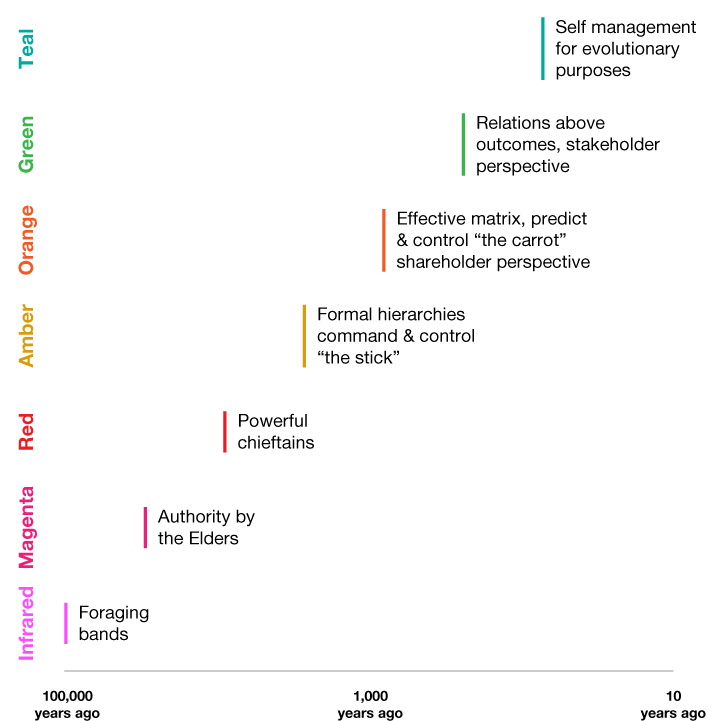

Frederic Laloux gives us a wealth of clues in Reinventing Organisations. First of all he explains the history of organisations based on how their power relations are distributed and what role the individual conscience plays. Each stage and structure is assigned a colour. He starts with magenta for the most ancestral communities, followed by the tribes or wolf packs (red, based on the regulation of chaos and fear). With the agricultural revolution appear the governors, hierarchical structures based on control and coercion (amber). Scientific advances and the industrial revolution give way to orange organisations, inherited by the majority of major corporations and based on competition, making a profit and chasing targets.

We changed hues a decade ago thanks to the information era, seeing the blossoming of green organisations, much more oriented towards relations than results, and where in addition to activists, importance is also given to suppliers and clients, who become the focus of attention. But what gives meaning to his whole book and the truly outstanding contribution made by Laloux are turquoise or teal organisations. More than organisations they are organisms, they function as ecosystems or neuronal systems, organised as a network of inter-dependent networks. There is no single brain, instead numerous centres coexist and vary according to the moment. It is the paradigm of decentralised leadership and decisions are taken in a distributed way, which all overturns the idea of organisation and structure that we had until now.

Source: Adaptation by Kevan Lee based on Reinventing Organisations

The arrival of the Internet and the social networks have made us aware of the importance of connections, and of the existence of collective intelligence as something much more powerful than the mere sum of the parts. Laloux, after spending over three years analysing 12 major organisations that exemplify this teal state of awareness, identifies the three main pillars:

- Autonomy or self-management, capacity for self-organisation and for making decisions.

- The wholeness of the person, beyond their professional dimension. In addition to the rational dimension, value is placed on intuition, the emotional and the spiritual dimensions. This is absolutely connected with the need to imbue with meaning what is done, and how and why it is done.

- The purpose: teal organisations are oriented towards changing, dynamic and evolving purposes. That living being, that organism knows where it is going, unlike a cog turning impervious with millimetric precision in a machine.

In reality Laloux recovers notions and analogies already proposed by the early sociologists (Spencer, Durkheim),[1] [2] with the difference that they talk about the system without taking into account the individual agency, while Laloux talks about resilient “organisms” connected to a greater purpose. But let’s go back to those windows. They were born and continue to be pure amber: maximum hierarchy, a high degree of specialisation and absolute disconnection between the parts. The time has come to dye the administrations, setting a course for flexible, distributed spaces with a shared purpose and meaning.

By way of example

Although a priori it may seem complicated, we have identified inspiring examples within the public sector. The driving forces for change are motivations, in many cases similar to those we find in the private sector. Understanding the starting point is important because it explains the commitment with the transformation process.

The service vocation of public organisations – a fundamental purpose – is experiencing a crisis of confidence on the part of society. Some institutions have decided to face up to this challenge and are working to recover their functional DNA. This is the case of the Municipal Music Conservatory of Barcelona which, led by David Martí, the manager of this organism over the last 20 years who today considers himself to be “a man without a position”, has given birth to “Bruc Obert”. This is a programme that opens the doors of the conservatory to “give back” the music to citizens, from the profound knowledge that musical practise is inherent to every human being.

Another important challenge, a consequence of rigidity, is the slow pace with which public organisations deal with change. Now that the pace of social change is accelerating, the equation between obsolescence and usefulness is dizzily increasing the distance. Arriving late (or never) at determined innovations condemns them to a loss of meaning. When the structure is not obliging, the solution begins with people. For example, training members of the organisation to learn to work in a collaborative way. To look no further, for the last ten years the Public Health Agency of Catalonia (ASPCAT) – followed and inspired by the model of the Catalan Government’s Department of Justice – has consolidated a knowledge-management model based on communities of practice (CoP). These work on specific problems in the work environment through a collaborative process of collective intelligence that requires passion and generosity from participants, so that ideas and solutions can be generated that are easily applicable to their reality. In ten years they have created more than 70 CoPs where over 800 people have worked creating knowledge products that have solved common recurring problems in the different professional groups of the ASPCAT (veterinarians, pharmacists, nurses, doctors, psychologists, anthropologists, etc.).

Along these same lines, in 2014 the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC) began the programme Nexus 24, through which all Administration and Services staff are offered an environment for learning and collaborative work practice applied to cross-departmental projects that help to improve the university’s functioning. The purpose of this programme is that, by 2024, working in collaborative teams is the norm at the UPC. In three years they have launched four editions in which 180 people have been trained in collaborative practices, resulting in 20 innovation projects, 17 new support services for collaborative innovation and 1 research project on the very transformation that they themselves are experiencing. And most important of all, the staff who have participated have recovered the meaning of their work, their motivation and they want to continue working in collaborative spaces.

The more advanced version is committed to making a break with bunkers (departments that function as closed, vertical compartments that are disconnected from the rest), shaking up the organisational structure and giving a much greater margin to autonomy. This is the case of the European Union Agency, an agency of the European Commission charged with supporting SME to carry out disruptive innovations in the market. In 2014, they organised one unit of the agency (there are over 60) into three areas, oriented towards user service. Each area has a leader who acts as a team coach, and whose mission is to help team members to define the pathway of what they are doing. The three teams work independently and are responsible for the personal development of the staff who form part of them.

So then, where to begin?

In the transition towards teal in the examples mentioned, there are various common and essential elements involved:

- Behind each story lies a vision that is sustained by at least one person and with which that person manages to infect a first group of enthusiasts charged with putting it into practice. These visionaries do not necessarily occupy posts in the senior management (although they always have a coordination position), therefore the change is proposed as a long-distance race with small victories that lead to the next step.

- The key to success of this route is in demonstrating tangible results and in not neglecting those who do not understand the new practices.

- These teal patches generate new forms of relations between the members of the organisations that form part of the experiment, creating a coexistence between the formal hierarchical structure that already exists and the new structure that has just emerged. An important role for the leader promoting this initiative is to hold up what Laloux calls the “shit umbrella“, to protect the promotion team and enable it to carry out its experimentation.

- The transition generates change in people and promotes their personal development. This is very significant as it marks a point of no return; “going back to the old way” means putting a blindfold on after having experienced how to grow and develop while working. Although the institutions are immovable and impassive, the people that form part of them need purpose and meaning.

- In many of the examples mentioned, the teal route is accompanied by practises geared towards wholeness and they have common schools, such as the Art of Hosting, Non-Violent Communication, etc. Surprisingly, many begin with Laloux, but as a catalyst rather than a guide.

- In reality, the service vocation is a purpose is constantly changing by nature, but the administrations that apply active listening could evolve with and for citizens.

The good news is that to start to be dyed teal, a 180º turnaround is not needed. It is possible to start with a few cracks, especially if there are leaders with the possibility of generating a project outside of the formal structure. Organisations themselves, depending on the person, the process or the point of the project may be in different colours. It may even be that your own organisation is already a rainbow.

[1] Spencer, H. (1898). The Principles of Sociology. New York: D. Appleton and Company. Vol. I-III.

[2] Durkheim, É. (1893). De la division du travail social. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. PhD thesis.

Leave a comment