Beryl Booker Trio. New York, 1946 | Bunky’s pickle

The concept of “the public” is going through the same changes as that of feminism: just as feminism has become “feminisms”, the public has been replaced by “publics”. In terms of the cultural world, this means that now more than ever it is necessary to identify different audiences, to analyse their distinctive features and their dissimilar behaviour. Given that women seem to make up the majority of cultural audiences, they must be taken into account. Women queue up for exhibitions, enrol in courses, take part in guided tours…. But do they see themselves reflected in the content of cultural programming, or are they treated like second-class audiences? The fact is that in spite of their large numbers, they function as minorities, like what Nancy Fraser dubbed “subaltern counterpublics”

This article is not an example of data journalism because there is an alarming lack of audience data broken down by gender – a trend that needs to be reversed. If we dive into the websites of some of Spain’s major cultural centres, we find data such as: in 2012, the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía received 2,572,414 visitors (to its various spaces), and some exhibitions were seen by up to 300,000 people. In the same period, the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona received 710,447 visitors. MNCARS breaks down its figures according to whether visitors are Spanish or foreign, but not by gender; and MACBA collects data on whether visitors fall under the categories of general public, families, schools, and experts and/or university students, but does not make a distinction by gender.

In Paris, the Centre Georges Pompidou received 3,791,479 visitors this year, and offers a breakdown including categories such as under-35s and liberal professionals, as well as people who visit in a group and those who see the exhibitions with or without a guide. And it also collects the information that interests us here: 56% of visitors to the Centre Pompidou were women. The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York goes further, and its website also includes answers to questions such as “How many women have exhibited at MoMA?” and “Who was the first to do so?” (Therese Bonney).

In Spain, our major public cultural centres – which have a privileged position as prescribers and disseminators of culture both in terms of their budget and their scope – are obviously not too interested in this apparent majority of female users. We don’t need to know how many women go and stand before Picasso’s Guernica each day, but some basic figures on gender would help to put together programmes that meet the cultural interests of the people they are genuinely intended for, which is not cultural managers but audiences, including the female audience. If we had that information, then we could do data journalism.

The origins of the public

Although in The Republic Plato argued that education should be compulsory for both sexes, women were not present in Classical Greece – or rather, they were present, but they weren’t entitled to participate in the Agoras of what we now call the public sphere. Classical Greek society had a category of free citizens (politai), and although ‘pariahs’ (foreigners and slaves) could earn the right to become part of it, women were banned from moving up in the world: without voice or vote, they didn’t count in politics or, obviously, in culture. And although the Greek polis is now far behind us, the predominance of the male voice remains, regardless of the fact that cultural spaces are overflowing with skirts, high heels and make-up: but always in the audience.

The public sphere was political, and being part of the public was a reserved for men, as reflected in the etymology of the word: it was initially derived from the Latin poplicus (people) and evolved to become publicus, in connection to pubes, in the sense of adult men, linking what Michael Warner calls “public membership” to pubic or sexual maturity. A perverse alliance between etymology and history in which the public realm became male, and the private realm female. This was the two-sided space that the second wave of feminism tried break down, with at least partial success.

The traumatic occupation of the public sphere

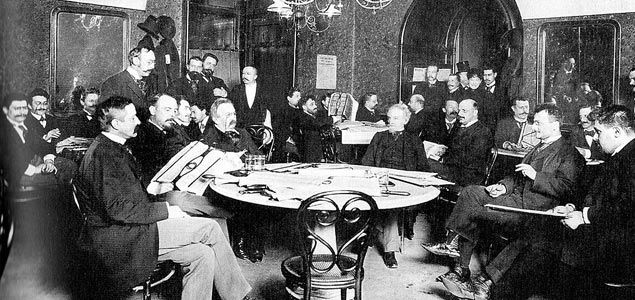

The external appearance of the public sphere, traditionally occupied by men, has changed a great deal in the last hundred years: one great step forward was the invention of the moveable-type printing press (way back in the fifteenth century) although it was undoubtedly film that “democratised” culture. In the early twentieth century, there were still cafés that were frequented almost exclusively by men (particularly the ‘cultural’ cafés of the time, such as El Café Gijón in Madrid). These kinds of images have now been relegated to photographic archives, and the public sphere is now the living image of life on the streets, including cultural spaces in which men and women freely indulge in the wholesome exercise of consuming culture.

El antiguo Café Griensteidl, punto de reunión de los miembros del grupo “Joven Viena”. Source: Wikipedia.

Partly due to having being denied it for so long, culture has always enjoyed great prestige among female publics, urged by their curiosity and multiple skills (to quote Amartya Sen). More recently, several factors have come together to increase the presence of women in a range of face-to-face and virtual forums, such as the reinvention of the public sphere and the start of a new cycle based on different dynamics that are already starting to make themselves felt (football, for example, and its audiences that are tending to become less male-dominated).

But the fact that women’s conquest of public space has made them resilient patients blurs reality somewhat. Because instead of throwing themselves into conquering their legitimate right to become active agents of culture as well, they resigned themselves to the role of attentive listeners of radio programmes and television talk shows, appreciative spectators of theatre productions, devoted followers of media-friendly gurus, diligent students of creative writing courses…

The path from not existing – in political-cultural terms – to participating in politics and culture on equal terms has been so arduous, that even if the scars of that long pilgrimage are not visible to the naked eye, they are there, and they are visible to sociology. This is why, given that women have in a sense only recently joined the ranks of consumers of culture, their role as audience or audiences deserves to be specifically taken into account. This late and traumatic incorporation into the public sphere has made women a “counterpublic”, or in other words, a public that does not fit the dominant paradigm, and is defined by its tension in relation to a larger public (in this case the male audience, which is not larger in numbers but in terms of its social importance).

Cultural consumption today

In the last two decades in Spain, the existing cultural facilities that survived (mainly because of their artistic real estate value) have been joined by big new cultural centres that are intended to be storehouses of art and culture: contemporary art museums in ground-breaking buildings, cultural centres that look like factories, and ingenious artefacts designed to house innovative projects that can keep up with the fast pace of the contemporary world.

The nineties saw the emergence of new audiences that had already started to show up at events such as festivals (particularly music festivals such as Canet Rock…), which suddenly had spanking new spaces to occupy: buildings specifically conceived to shape them as consumers of culture. So just as they threw themselves headlong into consuming in general, new generations also threw themselves into consuming culture, becoming something like a captive audience.

The 50% of women who were part of these new generations, which had grown up in the shared space, were also channelled into a kind of cultural consumption that was not determined by social classes, or by purchasing power, but simply by interests and curiosity. This was how the stages of culture were filled by an eminently female audience, to the point that we don’t blink an eye when we see more women than men at a concert, at the theatre, or listening to a lecture (nobody would dream of mistaking them for a Tupperware party), although we are surprised if the opposite occurs: a hall in which most of the audience is male is bound to make us think of a rifle association meeting or a conclave, at the very least.

The fallacy of mixed publics

The fact that Spain was the last Western European country to allow women to enrol at universities will obviously have left its mark in the evolution of cultural audiences from inexperience to maturity. Indeed, as the National Statistics Institute confirms, more female than male candidates sit for university entrance exams, and the majority of students in all but technical degrees are women. Similarly, women outperform men by 10% at the undergraduate and Masters levels. Even so, women make up less than 20% of professors.

By the same token, women are still banned from full access as creators of culture, which is why it is unfortunate that, as audiences, we don’t always find the mirror that reflects us as it should. Not because of the quality of cultural content itself, but due to the frequent underrepresentation of female voices that we can identify with, which is what ultimately encourages cultural consumption: culture engages us when it talks about us, regardless of how.

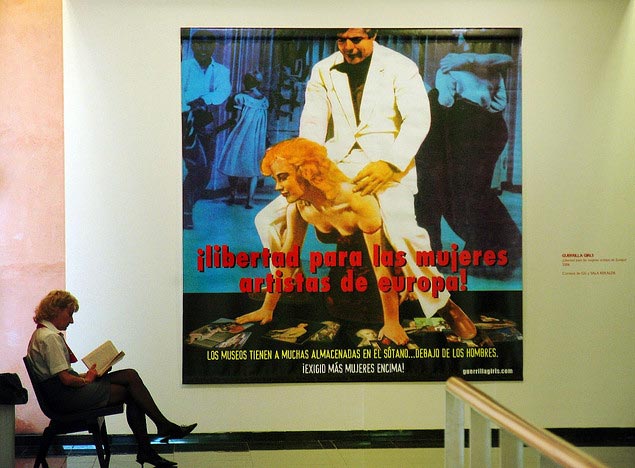

Source: jd (A).

This creates a divide between female publics – women as consumers of culture (readers, museum visitors, etc.) – and the low numbers of women who generate cultural content (writers, theatre directors, solo violinists, visual artists…), which inevitably sets up a gap between male and female audiences, to the detriment of the latter.

Because if an audience is a kind of alliance between strangers, the strangers who come together in female audiences have a lot more in common with each other than other subgroups, such as their status as a counterpublic for example. This leads us to deduce that mixed audiences are not really mixed, or at least not on equal terms. It is depressing enough to have been a minority – in spite of the numbers – subject to flagrant injustices in the past, but it is even worse to still be suffering the consequences of that grievance well into the twenty-first century.

Even though Hannah Arendt argued that the private dissolved into the social realm in the modern world, it seems to be turning out to be difficult for us women to totally dissolve our privacy in it. This is why our situation as audiences so closely fits the situation that Nancy Fraser expresses so well when she writes about subordinate social groups in reference to subgroups (women, ethnic minorities, gays, etc) who “have no space for deliberation among themselves about their needs, objectives, and strategies” and as such become alternative publics which she dubs “subaltern counterpublics”.

The fact that the largest public in numerical terms should also be a subaltern counterpublic can only be interpreted as a social anomaly, a shameful burden of the patriarchy. Women become a public/counterpublic that is forced to reformulate everything that it is offered culturally, like a gay teenager who is forced to read books or see films that focus on the heterosexual experience in the light of his homosexual experience. The small number of women among the prescribers of culture, the few stage productions created by women, and the stereotypical, unnuanced image of women in films, novels, and other artefacts of fiction, are unlikely to fulfil our “interests and needs” (as Fraser puts it).

How many female classical music fans have never seen a female orchestra director? How hard is it to see a film directed by a woman in cinemas outside of the major cities? The female audience is subaltern, this late in the game, while the male audience is dominant in the sense that it is closely connected to what takes place on stage, which is still governed by what Claude Lévi-Strauss called tribal rules.

Sharing culture in the global era

Culture is also legitimised in newspapers and on radio and television stations; on stages and on screens; in auditoriums and in museums. It is legitimised in the programming of the major cultural centres and in that of the more modest satellites that follow their orbits in various fields, at different scales and with different objectives. Culture is legitimised if it generates interlocutors rather than clients, if it encourages debate rather than silence. Hence the importance of “collective world-making through publics of sex and gender” (Warner).

But how can we aspire to a shared culture in the face of the obvious inequality pointed out by the female visual artists association MAV, for example? In its Report number 12 (March 2014), this group details the underrepresentation of women artists in some major cultural centres in Spain between 2010 and 2013. Here are some of the figures included in the report: IVAM (13.23%), Fundació Tàpies (13. 63%), CAC (17.9%), MACBA (19%), Artium (25%)… Given this scenario, we must develop a critical culture that also encompasses gender in order to treat audiences on an equal basis.

And there is another element that tends to be regressive, but is rarely taken into account when we consider the slow progress towards equality in the cultural sector. As Mario Vargas Llosa reminds us in La civilización del espectáculo, unlike the field of science (where a discovery overrules the ones that came before), a substantial part of what we call “culture” (letters and the arts) does not progress: “they do not wipe out the past, they build on it, they fuel it and they are fuelled by it.”

So we can spend hundreds of years reproducing the myth of Oedipus in a thousand variants, for example, or revisiting La Gioconda, quoting Virginia Woolf, or reformulating dance based on the foundations laid by Isadora Duncan and Pina Bausch. This said, and without downplaying the rereading of the classics, so strongly championed by Italo Calvino, something is going wrong today if more equal audiences are being created at the expense of less equality in other areas. And it seems unlikely that the insistence of reproducing the Greek model where men talk and women listen is going to be a contributing factor to change.

Technologies are altering cultural consumption habits: people who didn’t go to movie theatres now watch films on the Internet; when it rains and you can’t be bothered to go out you can watch a debate via streaming; museums offer virtual tours and YouTube has become a huge cultural media library. All of these changes are bound to herald changes in audience profiles, and it is a good idea to flow with them so that the relationship between culture and cultural audiences can become increasingly fluid. If women are to stop being considered a counterpublic, we must understand the mechanisms by which women are incorporated into this being fully public. This will also allow the spaces of culture to become today’s Agoras, places of that public discussion that Habermas considered such a useful tool for repairing democratic shortfalls.

Bibliography

Hannah Arendt: “The Public and the Private Realm”, in The Human Condition (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1958)

Jürgen Habermas: Historia y crítica de la opinión pública. La transformación estructural de la vida pública (Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 2004)

Nancy Fraser: “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy”, in Craig Calhoun (comp.), Habermas and the Public Sphere (Cambridge, MIT Press, 1992)

Mario Vargas Llosa: La civilización del espectáculo (Madrid, Alfaguara, 2012)

Michael Warner: Publics and Counterpublics (Cambridge, MIT Press, 2002)

carmemix | 13 August 2015

Hola CCCBLab, heu retirat el botó sharing d’impressió? La veritat és que era molt pràctic i còmode oider imprimir els textos tan interessants que editeu i llegir-los amb calma. Pregaria que us ho repensessiu. Salut i gràcies!

Equip CCCB LAB | 14 August 2015

Hola Carmemix! Ho comprovem i intentem arreglar-ho tan aviat com sigui possible, ja que es tracta d’un error. Moltes gràcies per avisar-nos i pels afalags.

Més salutaciones per a tu!

Leave a comment