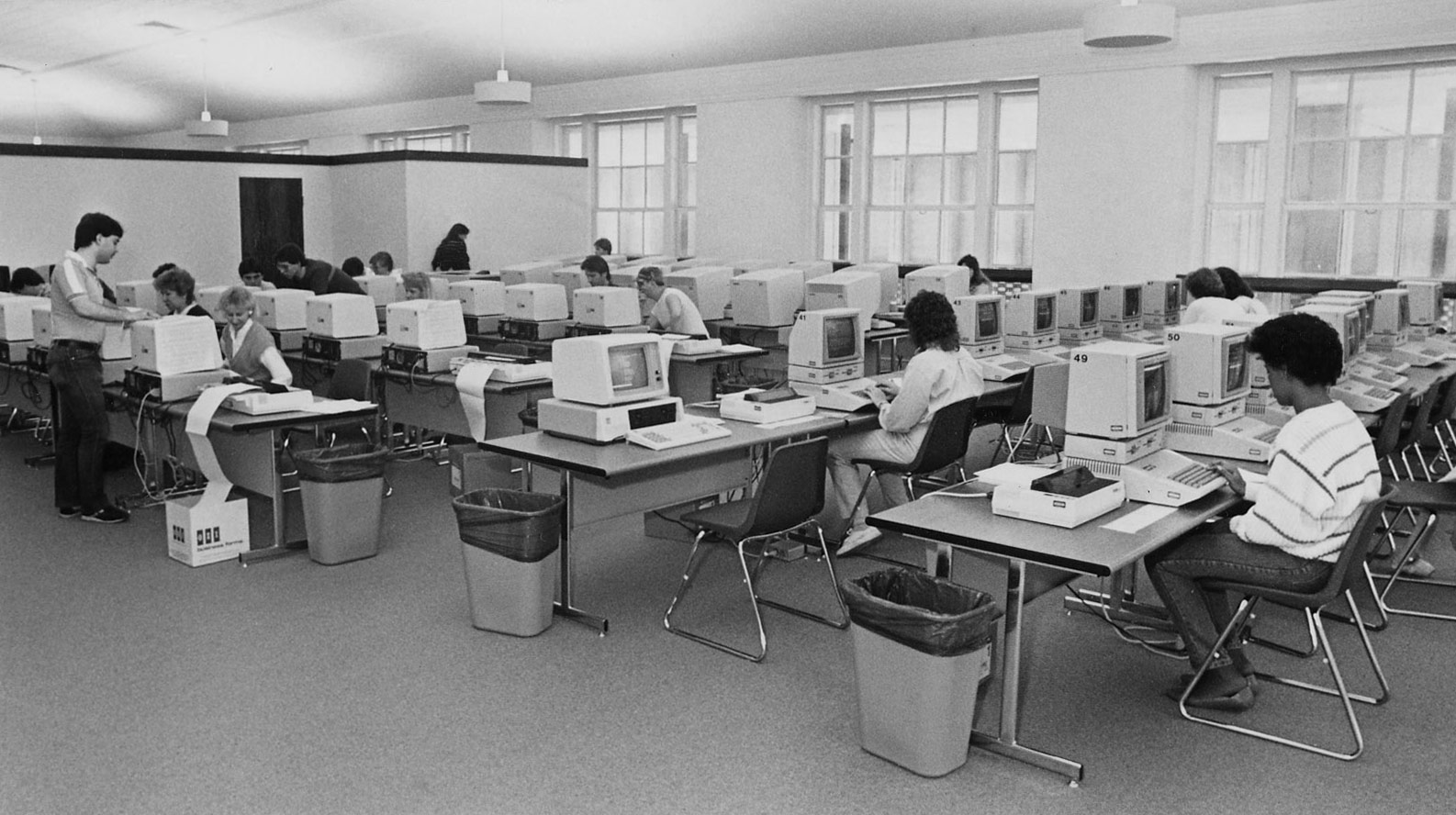

Computer Lab on campus of Southeast Missouri State College, Cape Girardeau | Missouri State Archives | Public Domain

For some time the debate on digital technologies has been present in the educational environment. However, the true challenge is not whether to use technology or not, but to rethink education with it. Today’s technologies define a new learning environment that modifies our relationship with contents, requires new forms of teaching-learning, and blurs the boundaries between classroom and home, formal and informal education. In this sense, it it not only a case of developing a set of skills and abilities of a technical nature, but a combination of behaviours, specialised and technical knowledge, working habits, arrangements and critical thinking. Talking today about digital education is, therefore, something more than just talking about training in digital literacy.

The digital transformation is blurring the distinction between the real and the virtual; between the natural, the human and the artificial. “There is not a single instant in people’s lives that is not modelled, contaminated or controlled by some device”, argues Giorgio Agamben. We have forever changed the way in which we communicate, inform, work, relate with each other, love and protest, said Manuel Castells a few years back. Rather than changing between an online or offline state it is increasingly clear that we are living in a permanent onlife status. We live hyper-connected lives, says Jordi Jubany.

“Any technology creates a new environment”, affirmed Marshall McLuhan back in around 1962. Technology is not just a set of tools. It is not neutral. It is, argues Luciano Floridi, an environmental, anthropological, social and interpretative force that is affecting our conception of ourselves (who we are), our interaction with others (how we socialise), how we interpret reality (our metaphysics) and interactions with that reality (our actions). Technological objects are thoroughly enmeshed in society (Sheila Jasanoff). They influence and give form to our actions, in the same measure in which our actions give form to technological objects. Not only do they change what we do, but also what we are. When we design them, we promote and amplify certain behaviours and limit and reduce others. They define new forms of doing and new social and economic relations. And also, of course, new forms of learning and of teaching.

We have been lacking in profoundness and complexity when it comes to thinking about the impact of technology on our lives. We have fallen too easily into simplistic and highly polarised positions. We have shown ourselves to be deeply utopian, while unfurling the flag of the most radical technological Luddism. Avoiding this sterile dualism, says Neil Postman, involves making technology the subject of research, problematizing its acceptance and use, as well as its rejection and ignorance. We need new metaphors that help us to tackle new situations. We need other ways of imagining and articulating relations between individuals, their tools and society. We need digitally critical and reflective citizens (DigCom 2.1). We need citizens who, as Iván Illich suggested, are in control of their tools.

Rethinking and developing new forms of education are some of the most important challenges of our times. The challenge is not whether to use technology or not, but rethinking education with it. Obtaining the best of technologies means, as Neil Selwyn argues, being prepared to think about the worst, but also being capable of imagining the best.

Technology has always been important in education. Our current schooling organisation owes a great deal to the most efficient educational technology of all time: the textbook. It is important, therefore, not to allow ourselves to be carried away by the usual educational amnesia and remember that a close relationship has always existed between education and technology, but also, that the history of educational technology is full of futures that have never been presents.

Technologies entered education some time ago but on the majority of occasions did so in an unequal, fragmented way from a restricted and limited conception of them, barely modifying teaching processes. We find technologies in the offices and in the classrooms, in administrative processes and in communication with families. Teachers increasingly use technologies to prepare their lessons and students to search for information and produce their work. However, in the majority of cases, they continue to remain outside the pedagogical project at the centre and of the central core of the teaching-learning process. Technology remains on the periphery. It is still very much a pending issue to develop a pedagogy with, for and on the internet.

Confirming that educational change through technology has turned out, to date, to be an unfulfilled promise, should not lead us to be pessimistic about the transforming potential of technology in education nor, of course, to abandon the idea of educating with and in technologies. All the more so when, as we said, today’s technologies, far from simply constituting a toolkit, define a new learning environment that, among other consequences, is expanding the concept of literacy training, modifying our relationship with contents, demanding new forms of learning-teaching and blurring the boundaries between the classroom and the home, the formal and the informal.

They constitute a new environment that must be mastered by students and teachers. The solution does not involve banning them. The gap between social (informal) use and school (formal) use has to be closed. “Technology is part of our lives, expanding them and at the same time generating its own complexities. Educating for life is the school’s mission and what we have, whether we like it or not, is a life with technology with its lights and shadows. Ignoring it is not an option, but nor is adopting it without any critical spirit” (Tíscar Lara).

Preparing for life in this new digital environment means developing, among other things, the necessary competencies for understanding and making use of digital technologies, not only as a set of skills and abilities of a technical nature, but as a combination of behaviours, specialised knowledge, technical knowledge, work habits, arrangements and critical thinking.

We are neither digital natives nor digital immigrants. Nor are children digital natives who need, therefore, little support to get the best out of the digital media. There really are very few children who receive sufficient guidance at school or at home and many, in contrast, who lack the necessary abilities for making any creative use of technology. Rather than access to technologies, our main problem now is the use that we are capable of making of them. Today, the digital divide is what separates those who are capable of using technology in a reflective, active, creative and critical way from others that use it in a passive, consumerist and non-reflexive way. A divide that is not new and that reproduces, and even expands, the traditional and still existing educational inequalities caused by cultural, social and economic capital. We continue lacking reflective, critical and didactic competencies related with technologies. We need students, teachers, education centres and citizens trained in digital literacy.

Lucélia Ribeiro | CC BY-SA

Talking today about digital education is, therefore, something more than talking about training in digital literacy. It is understanding, as we said, that the new context in which we are living affects all the parameters of the teaching/learning process: the where, when, with whom and from whom, how, what and even for what people learn. It means assuming that changes must occur simultaneously in the curriculum, assessment, teaching and learning practices, school organisation, leadership, infrastructures, spaces, times and professional development for teachers. Talking about digital education is talking about digital citizenship and about the empowerment of students. About the active participation of students in learning (ABP, Flipped Classroom, Gamification, Maker Movement) and connections with the “real” world (learning communities, service learning, etc.). About digital pedagogies and about teachers sharing practices online (aulablog). About computational thinking (IBI) and technological disobedience (Cristóbal Cobo). About creativity and knowledge production. About innovation and collaboration. About making with technologies, but also about making technologies. About thinking with technologies and thinking about technologies.

Talking about digital education means talking about the digital competence of education centres (the European Union’s DigComOrg; MOOC Intef DigCompOrg), about digital teaching competences (the European Union’s DigCompEdu, Marco Común of Competencia Digital Docente-INTEF) and about the digital competences and skills of students (ISTE 2016, Digital Skills for Life and Work. UNESCO. 2017).

In recent years, we have started to see detailed approaches about how to develop digital competence in the curriculum (Desarrollo de las competencias informacional y digital. Gobierno de Aragón, Modelo Competencia Digital de Gales). Instruments have been published, such as the Portfolio de la Competencia Digital Docente by INTEF, to measure the digital competence of teaching staff and tools for helping education centres to reflect on the implementation of digital technologies in their educational self-assessment practices such as SELFIE. The traditional divide between theory and practice is starting to close. It will be completely closed when we stop talking about digital education to talk only of education. Resolving the challenge of the integration of technology into education means resolving the challenge of education.

Technologies represent an opportunity to transit, finally, from purely transmission-based teaching models to active learning models. They are a second opportunity for progressive pedagogies (Seymour Papert). They can serve to encourage experiential learning, active pedagogies, cooperative learning and interactive pedagogies. They can serve to form critical, inquisitive and participative citizens, even annoying citizens, and not simply students who change from one year to the next, pass exams and achieve good marks.

The major opportunity that technologies offer puts us before the responsibility of understanding them and making use of them correctly. An approach that, at the same time, permits us to imagine and build an inclusive information society that encourages equality, participation and human wellbeing. Education has an important responsibility in the development of our capacity to think independently and criticises our use of digital technology and the digitalisation of society.

The digital transformation can lead us to many places. It can take us along highly dystopian pathways or the complete opposite. Where we will reach, both in the educational field and in society in general, will largely depend on us. It will depend, ultimately, on our capacity to construct brave, coherent, inspiring and realistic future visions. On our capacity to think, construct and inhabit this new environment not as a space for competitiveness and individualism but as an own place that must be preserved for the benefit of all. The question that we have to ask ourselves, paraphrasing Richard Rorty, is whether our future could be made better than our present, and what we can do to make things better.

Silvina Sala | 11 January 2018

Impecable artículo! Una claridad absoluta en los conceptos y tan bien documentado. El desafío de educar para esta sociedad actual con tecno por doquier, y todas las posibilidades que implica. Siendo bibliotecaria siempre atenta al lugar primordial que considero ocupan los contenidos de calidad más allá del formato en que se presenten. Sldos desde Buenos Aires.

Roser | 12 January 2018

Discrepo, com sempre, en l’afirmació que els alumnes NO són nadius digitals. És com si afirméssim que un alumne que no sap compondre un poema o extreure informació de qualsevol tipus de text, no és un català nadiu, per molt que hagi nascut a Catalunya dins d’una família catalanoparlant.

Els alumnes són nadius digitals, però som l’escola els qui els hem d’ensenyar a utilitzar aquesta eina, que s’han trobat a les mans des del dia que van néixer, per créixer com a persones. Com els ensenyem a manegar les emocions, expressar-se literàriament, a fer operacions complexes o a observar el món amb ulls (i esperit) de científic. Tots saben parlar, emprar un mòbil, tots tenen sentiments i tots són capaços de crear teories sobre el funcionament del món que els envolta, però és feina de l’escola convertir-ho tot plegat en quelcom útil.

Que ells siguin nadius digitals no ens eximeix dels nostres deures docents: el guiatge, la bastida, l’acompanyament.

Rubén Darío | 07 July 2021

La alfabetización digital tiene como recurso el lenguaje visual; que ha ido complemento del camino y desarrollo de lenguajes interactivos e informáticos. Ha sido necesario a priori que se reconozca lo que aquí afirman, pero también sostener que esa brecha generacional-actual con pilares que fueron y han sido mayor referencia en este tema.

Leave a comment