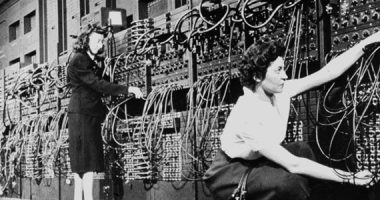

Kids Hacker Camp, iHub Nairobi. Source: iHubNairobi.

There is an Africa that is in tune with technology: this is not a hypothesis, it is an affirmation. There is such a thing as a technological Africa; a digital Africa; an Africa 2.0; a connected Africa. There is an Africa that innovates and looks to ICTs as a means to solve its problems, and that is determined, in spite of its shortcomings and difficulties, to ensure that it seizes the opportunity of the information society to get on the train that it was forced to miss in the industrial revolution, for example. In short, there is an Africa that wants to take control of its future on many different levels through a citizen-led process.

A billion people live in Sub-Saharan Africa, half of them young people below the age of twenty-five. Up until the start of the 20st Century, Africa has been extremely deficient in technology and infrastructure in general, but what will happen from this point onwards? A process of democratisation and increased access to technology is taking place all over the world, and Africa is no exception. Sure, it’s lagging behind other countries, and the process is slower than on other continents. But the shortfalls, problems, and obstacles that had to be negotiated in Africa are precisely why the implementation of the information society has certain specific characteristics in African countries. One of these characteristics is the fact that citizens have placed themselves at the centre of the process. Civil society and individual initiatives in Africa are much braver, more cutting-edge, and more constructive than those of the governments of countries that are a step behind communities of connected citizens.

Less than ten years ago, in 2005, barely two percent of Africans (including North Africans) were connected to the Internet; today, nineteen percent venture online. This percentage is clearly still much lower than the worldwide average of 40.4 %, but it’s just as clear that the gap is closing at a dizzying pace. The number of African internet users this decade has increased by more than a thousand percent. The internet penetration rate worldwide is twice that of Africa, but ten years ago it was seven times greater.

This connected Africa is a multifaceted prism. ICTs are used in the agricultural, cattle and fishing industries (not just for marketing products), and in health and education, for example, and the first tentative e-government initiatives are starting to emerge. In addition, technological innovation is becoming an economic sector in itself, one that is governed by different laws than those that regulate the exploitation of raw materials and as such opens the door to different types of commercial and financial relationships. But above all, web 2.0 tools are providing civil society with a means by which to develop their interests, promote social and political participation, denounce democratic deficits, supervise election processes and governments, draw attention to abuses: in short, to shame those in power and to become catalysts for change.

Digital Africa is a complex ecosystem, both within the 53 countries that make up the continent and among them. A huge number of actors are involved, from governments to transnational corporations; from individual internet users to civil society groups that are colonising the virtual environment; from creative entrepreneurs to companies from other sectors that seek technologies tailored to their needs. All the different initiatives are interconnected: they fuel and inspire each other and awaken new interests, and the actors interact and generate new realities. The points of contact between all these elements multiply, increasing the complexity of the ecosystem. At the same time it grows, attracting new actors and new initiatives in a dynamic of expanding connections that constantly exceed the established limits. Notwithstanding the fact that every situation is different, and that it is always dangerously to start talking about “Africa” in general terms, there are some recurring elements that appear to characterise this phenomenon :

It is an urban phenomenon that is becoming less restrictive

The difference between the rural and urban worlds is almost the norm all over Sub-Saharan Africa. Infrastructures have grown considerably in most cities, while in rural areas they remain bogged down. The urbanisation of the continent is taking place at a dizzying rate, almost as fast as the implementation of ICTs. At the moment, around 40% of the African population lives in cities, but forecasts suggest that one of every two Africans will live in urban centres by 2035, rising to almost 60% (more specifically, 58%) in 2050. But we don’t need to look that far ahead: by 2015 three African cities –Lagos, Cairo, and Kinshasa– will have a population of more than ten million, while only thirty years ago the figures were 3.5 million for Lagos and 2.7 million for Kinshasa.

In the most major African cities, fifty percent of the population has internet access. (while the average for the continent, as mentioned earlier, stands at 19%). And the majority of university-educated young Africans –who match the profile of the most common internet user– live in these urban centres. In spite of these differences, many initiatives are aimed at bringing internet access to rural environments. Internet activists themselves believe that expanding into the countryside is one of the basic challenges for the democratisation of the internet, and increased mobile bandwidth is turning out to be their main ally.

A hackathon at the iHub in Nairobi to find technological solutions to natural disasters and crises. Source: Erick (HASH) Hersman.

Appropriation of technology, reuse, recycling, and adaptation

The potential uses of ICTs in Africa have grown exponentially because the main actors rarely stop at the prescribed uses for pre-existing tools. Adapting technology to specific needs has become the main concern of users (at least those who are most actively involved), either by designing and making new devices, adapting existing tools or, at the very least, devising uses other than the ones they were designed for. At one end of the spectrum, there are many initiatives that try to breathe new life into electronic waste through ingenious, creative recycling, in an attempt to avoid the terrible fate of becoming the dumping ground of the information society.

Cyberactivism and technological innovation

Two particularly striking phenomena have emerged in the expansion of the African digital ecosystem. On one hand there is cyberactivism, by which civil society takes action in order to secure a greater role in social and political processes through the use of ICTs. On the other, there is technological innovation, which has found its ultimate expression in the emergence of tech labs o tech hubs: co-working spaces and business incubators, which are the ideal breeding ground for technological social entrepreneurship and developing start-ups based on social awareness. These two phenomena overlap, interact and feed off each other, in a complementary and collaborative spirit.

Transnational relations

The small scale of local communities probably helped to make it easier for users to get to know each other and develop interpersonal relationships. As the communities grew larger, these bonds made the connections grow stronger. In the current situation, these connections have led to joint initiatives: users are aware that other actors in the ecosystem (such as transnational corporations) cross borders, and that some of the challenges that they are facing involve more than just one country. So the most natural thing to do is to join forces in a virtual space without borders to meet those challenges.

The transforming spiral

As the development of the African digital ecosystem is recent, we can trace its evolution. One of the recurring triggers was a response to political crises, which led to a desire for social participation. This in turn gave way to direct solidarity, which then grew into civic activism. The most recent territory colonised by cyberactivists is environmental activism.

Users of a cybercafe in Kampala (Uganda). Source: Arne Hoel/World Bank.

A business, for better or worse

It is beyond question that technology is an important sector in the world economy, and that Africa is a rapidly developing market. On one hand, it is a territory in which transnational corporations (including telephone companies, internet providers, and hardware manufacturers) are eagerly trying to position themselves. However, the presence of companies such as Samsung, Microsoft and Google in Africa is not only linked to their desire to sell their phones, distribute their software, and get people to use their “services”. The fact that they are also setting up development labs and approaching tech hubs as innovative spaces, shows that they are trying to make the most of the creative potential that African users have shown in a very short time. And that’s without counting the increasing impact of the internet on business and on the GDP in Africa, directly or indirectly. Curiously, none of the countries that are getting the most out of the virtual environment are what are considered the major economic powers, which until now had been economies with natural resources to exploit.

Future challenges and threats

In these early stages of the implementation of ICTs in Africa, citizens have overtaken governments. Communities of activists and innovators have proven to be much quicker, more flexible, and more creative than the authorities. Nonetheless, the fundamental future challenge is to make the internet more generally accessible. And this is not just a question of infrastructures and materials, it is also about continuing to work on education and digital skills, and to fill the net with content that makes Africans to feel at home. The current situation also contains the risk of the creation of a technological elite –a vanguard that could take advantage of their greater access to resources in order to accumulate power. But for now, the promoters of the major initiatives have not shown a tendency to hoard privileges. Instead, they are driven by a desire to work towards democratisation and social change. While a potential danger exists, the real experiences are all along this path.

Leave a comment