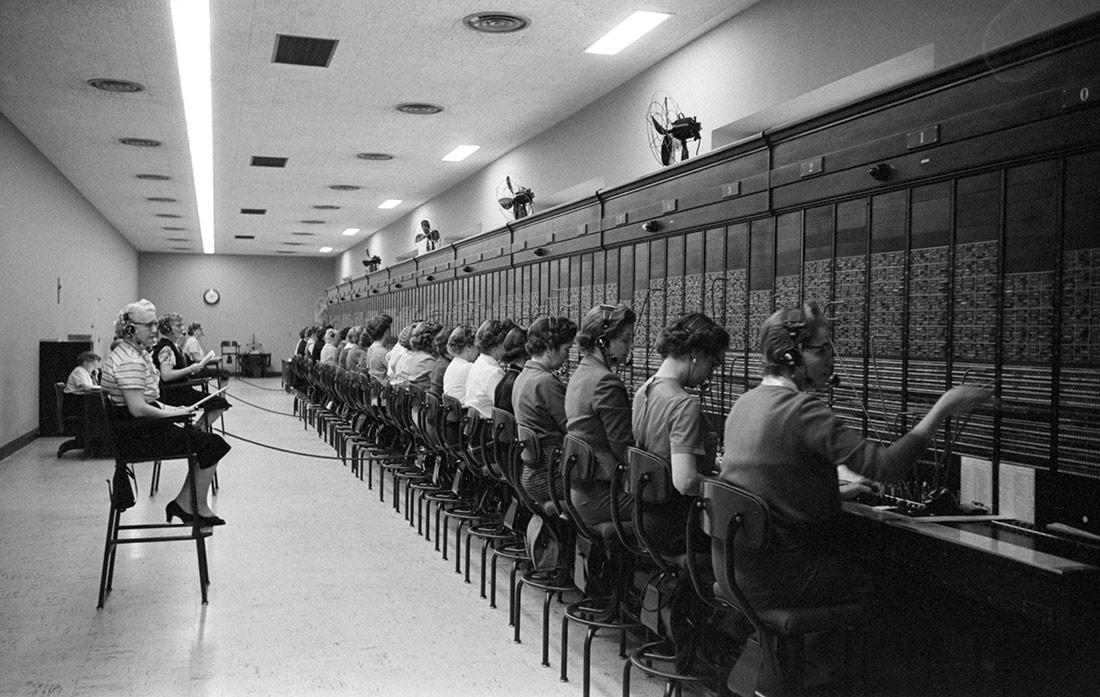

Women working at the U.S. Capitol switchboard. Washington, D.C. 1959 | Marion S Trikosko, Library of Congress | No known restrictions on publication

Far from offering a place for meeting and genuine exchange between two parties, the call centre seems designed to thwart any attempt at communication. Its logic forces us to renounce dialogue and submit to strict connective protocols. In this sense, the call centre is a prime example of what Franco “Bifo” Berardi has described as a “displacement of conjunction towards connection”.

“What exemplifies the failure of the neoliberal world to live up to its own PR better than the call centre?” asks Mark Fisher in Capitalist Realism. Is There No Alternative? (Zero Books, 2009): “The closest that most of us come to a direct experience of the centrelessness of capitalism is an encounter with the call centre, […] you increasingly exist in two, distinct realities: the one in which the services are provided without hitch, and another reality entirely, […] a world without memory, where cause and effect connect together in mysterious, unfathomable ways, where it is a miracle that anything ever happens, and you lose hope of ever passing back over to the other side.”

Fisher strikes a parallel between the call centre and the sinister telephone system that Kafka describes in The Castle. “There is no specific telephone connection with the castle”, the warden explains to the character in the novel; “no exchange that puts our calls through; when you call someone in the castle from here, it rings on all the telephones in the lowest departments there, or rather it would ring on all of them were it not for the fact, which I know for certain, that on nearly all of them the bell is switched off. […] And that’s very understandable, after all. Who has any right to ring in about his private little troubles in the middle of the most important jobs, which are invariably being done in a tearing hurry?”

The telephone system that, in principle, should serve to communicate with the administrative authorities of the castle turns out to be a device designed to thwart any attempt at communication. Something very similar happens when we enter the labyrinth of some call centres. Because, to paraphrase the castle warden, who considers themselves entitled to make a complaint or try to clarify some minor detail to the company that provides a service? Who dares to interrupt the tearing hurry of a big corporation with complaints or questions of any kind at all?

“The call centre experience,” maintains Fisher, “distils the political phenomenology of late capitalism: the boredom and frustration punctuated by cheerily piped PR, the repeating of the same dreary details many times to different poorly trained and badly informed operatives […] Anger can only be a matter of venting; it is aggression in a vacuum, directed at someone who is a fellow victim of the system but with whom there is no possibility of communality.”

ABSA Bank Call center. Johannesburg, 2008 | CC BY-SA Media Club

This lack of communality, so characteristic of the call centre, is a perfect example of the anthropological transformation that Franco “Bifo” Berardi describes in And: Phenomenology of the End (Semiotext(e), 2015). The consequence of this mutation, resulting from the current technological transition, is none other than “the dissolution of the modern conception of humanity and the extinction of the humanist man or woman”.

But what exactly is this mutation? Ultimately, it is an inability to empathize and a loss of “the ability to perceive the other’s body as a living extension of my own body”. Berardi attributes this neutralization of empathy and the affective to a “displacement of conjunction towards connection”. Whereas conjunction is “a concatenation of bodies and machines that can generate meaning without following a pre-ordained design, nor obeying any inner law or finality”, connection, conversely, is “a concatenation of bodies and machines that can generate meaning only following a human-made intrinsic design, only obeying precise rules of behaviour and functioning”. Conjunction, writes Berardi, “entails a semantic criterion of interpretation. (…) Connection instead requires a criterion of interpretation that is purely syntactic.” In other words, conjunction is empathic, whereas connection is purely operational.

This is why the labyrinth of the call centre becomes even more Kafkaesque and desperate when our call is answered by an automatic voice recognition system. When this happens, we have to adjust our words to a strictly coded communication, and the possibility of solving our problem depends exclusively on whether or not, on the other end of the line, it is considered a real problem. As Berardi points out, it is the empathy of the conjunctive plane that enables the appearance of a previously non-existent meaning. In the connective mode, conversely, “each element remains distinct and interacts only functionally”.

Unable truly to listen and understand us, the virtual agent of the call centre can only answer a limited number of questions and incidents, so if the reason for our call does not correspond precisely to any of them, the communication may be terminated regardless of whether or not our problem has been resolved. This is what Éric Sadin, in his book L’Intelligence artificielle ou l’enjeu du siècle: Anatomie d’un antihumanisme radical (Éditions L’Échappée, 2018), calls the “menacing power of technology”. Increasingly, writes Sadin, we bend to “protocols designed to bring about inflections in each of our acts” and submit to the equations of a series of artefacts that have the “primary objective of responding to private interests and establishing an organization of society based on primarily utilitarian criteria”.

The call centre continues to be one of the main testing fields for the predictive and interpretive capabilities of artificial intelligence. If, as Fisher suggests, public relations represent “the point of view of neoliberalism”, the robotization of the call centre implies precisely the dehumanization of the meeting place between salesperson and customer (or, if you prefer, to use a terminology more in keeping with the times, between provider and user). Public relations were traditionally based on a form of conjunctive, empathic communication between two parties; now, however, with the proliferation of systems such as speech recognition, they seem to work increasingly according to the rules of a connective mode and for strictly functional purposes.

On the other end of the line

However, the connective nightmare of the call centre is not just about the experience of the person making the call—far from it. When it is not a machine that answers the call, the voice we hear on the other end of the line is that of a person who is much more subjected than we are to the strict connective protocols that govern the operation of telephone service switchboards. That person, or the one sitting next to them, could be the same person who called us yesterday afternoon on behalf of some other company to offer us a service. It is likely that, on that occasion, the call was ended rather abruptly on our part. This fact highlights the perverse way the voice circulates at the call centre and explains why it so often becomes a place of misunderstanding and frustration at both ends of the lines.

Although Mark Fisher refers to the people who work in the call centre as “fellow victims”, it is important to realise that it is precisely these people who bear the brunt of this submission to a form of strictly connective communication. After all, nothing can be more dehumanizing than being forced to abandon empathy in order to function in a non-human way comparable to that of a virtual assistant. A few years after the publication of Capitalist Realism. Is there No Alternative?, in his compilation of articles Ghost of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Zero Books, 2013), Fisher compared the call centre worker to a “banal cyborg, punished whenever they unplug from the communicative matrix”.

“Somehow you become an appendage of the computer, but with a voice” writes an anonymous call centre worker in the pages of ¿Quién habla? Lucha contra la esclavitud del alma en los call centres (Tinta Limón, 2006). Published by Colectivo Situaciones, this book brings together the testimonies of various call centre workers in Argentina and takes an inside look at the dark reality of these workplaces that continue to proliferate around the world. As Jamie Woodcock and Enda Brophy analyse in detail in their respective books Working the Phones: Control and Resistance in Call Centres (Pluto Press, 2017) and Language Put to Work. The Making of the Global Call Centre Workforce (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), the call centre is a paradigm example of new forms of work that promote neoliberal business formulas typical of platform and/or surveillance capitalism.

Beyond the connective discipline to which their employees are subjected, call centres are also spaces of precariousness and exploitation. During the worst moments of the coronavirus pandemic, the call services not only didn’t stop working, they had to function at full capacity, becoming major focuses of contagion. The call centre represents the dark side (or, rather, one of the many dark sides) of digital economic expansionism. It is a photograph of a call centre that illustrates the cover of Ursula Huws’s book Labor in the Global Digital Economy: The Cybertariat Comes of Age (NYU Press, 2014). Here, the author examines the notion of “cybertariat” and the “destruction of occupational identity” within the framework of an economic model based on information and knowledge.

Converted into linguistic cogs in the “communicative matrix” of “iCapitalism” (Huws), call centre employees are the closest thing to production line workers in the post-Fordist era, constantly monitored by supervisors who, though remotely and silently, play the role of the factory foremen. Unlike the phone system that Kafka describes in The Castle, the call centre lines are always connected. If we get past the dissuasive preambles with which each call begins (the unbearable hold music, recordings about services or offers we don’t need, lists of options that don’t correspond to our problem or the classic passing of our call from one department to another), we end up talking to a person who most likely works under enormous psychological pressure to try to meet a series of unattainable objectives in exchange for meagre bonuses.

If, as Fisher writes, the call centre experience reveals the failure of neoliberalism, it is precisely because of its twofold collateral effect at both ends of the telephone line. Both the caller and the person who answers the call are condemned to give up empathy, typical of conjunctive communication, and submit to the rules of strictly syntactic, connective communication. The impossibility of “getting through” is reciprocal and invariably leads to a complete disempowerment of voice and word. In this sense, the call centre is the absolute reverse of what Brandon LaBelle, in his book Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance (MIT Press, 2018), calls “sonic agency”—that is, the possibility of establishing relationships between subjects and bodies with the aim of creating new forms of resistance and negotiation of reality using listening, voice and sound. Perhaps the most convenient option at this point (bearing in mind the depth and interest of the notion proposed by LaBelle) would be to address this issue more specifically on another occasion.

Leave a comment