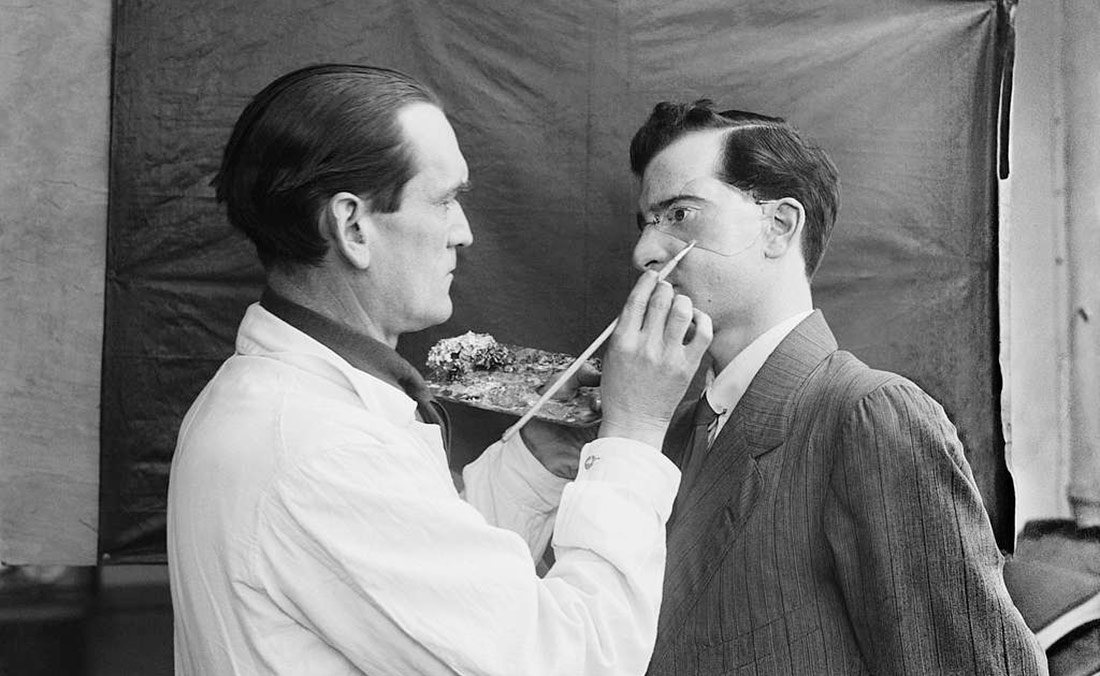

The development of reconstructive plastic surgery during the First World War | Horace Nicholls | © Imperial War Museums

The face is an important part of the body for our personal, social and even institutional lives. Control over facial recognition technologies gives those who wield it a level of power that may threaten many rights and freedoms. This has led to growing opposition to these systems in recent years, generating a public debate on the need to regulate them.

At the end of 2021, Madrid and Barcelona airports began testing a facial recognition system that allows passengers to check in, pass through security control and board their plane without having to show their ID card or boarding pass. The system, some media outlets enthusiastically announced, is so accurate that it can even identify the faces of people wearing masks. The influence of corporate marketing in how the news was presented was evidence that, as Henry David Thoreau criticised of his contemporaries, “there are some who, if they were tied to a whipping-post, and could but get one hand free, would use it to ring the bells and fire the cannons to celebrate their liberty”.

Everyone can see that facial recognition technology is a controversial tool by nature, given its ability to automate civic control on a scale and at a speed previously unimaginable. Its use is spreading through both public and private initiatives, championed by authoritarian governments such as China’s and by large companies such as Apple, Mastercard and Facebook, which for years have been using systems of this type in security functions and photo tagging.

From the laboratory to the archive

Although facial recognition technology is relatively new, its philosophical and political implications go back centuries. Prior to the digital age, various efforts were made to turn the human face into an object from which information could be systematically extracted. The oldest of these was physiognomy, the earliest efforts in which date back to classical Greece but which was developed especially in the second half of the 18th century. This discipline aimed to draw conclusions about character and personality from facial shapes and expressions. Also in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, phrenology was born, which considered that the shape of the skull was a reflection of the brain and that it could be studied to predict behaviours such as an inclination towards marriage, poetry and kindness, or also theft and crime, to give but a few examples.

However, if there is one discipline that is linked directly to contemporary facial recognition technology, it is that of police records management. The first system of criminal identification cards appeared in France in 1833, and in the following decades, other industrial societies became interested in analysing crime on a regional scale. As the image theorist Hans Belting points out, “the authorities wanted to protect themselves from the faceless threat posed by criminals, over whom they had lost control in the big cities, and so they feverishly developed appropriate methods of facial control”. This need resulted in the project to create an archive of faces, with photography as the tool that would guarantee the reliability of such an inventory. The aim was to have a census of all the anonymous people who blended into the masses, and this urgency was heightened by revolts such as that of the Paris Commune, when the authorities began a wave of repression that took in not just common criminals but also those convicted of political insurrection.

All these disciplines, however, soon revealed their limitations. Alphonse Bertillon himself, the architect of forensic policing, recognised in 1885 that photography was not a reliable tool for identifying criminals. As arrests were made in different places and at different times and the portraits were taken by different police officers, the images were subject to too many changes to guarantee their veracity.

A technology of exclusion

The problems of 19th-century control techniques were solved, paradoxically, when it was no longer necessary to observe. Facial recognition technology extracts the details of facial features and checks whether or not they are listed in a database. This means that, even using images as the raw material, the machine does not interpret them, but merely converts them into information.

This processing without a human eye to interpret and understand the context has led to widely known and decried errors. Machine learning works by looking for patterns in the real world, but to do so it must first use “training data”, which in many cases reflects and perpetuates the biases of the people who provide it. In 2018, a now-classic study by MIT and Stanford showed that the margin of error in facial recognition systems was higher for women than men, and even higher for black people than white people. In a demonstration of the problem that speaks for itself, the African-American researcher Joy Buolamwini showed that some algorithms failed to recognise her face, even though they did recognise an expressionless white plastic mask.

Although some companies have tried to correct these biases, the problem is a difficult one to solve, especially in terms of the predictive capacity of some algorithms. In addressing the discrimination within their systems, research centres have found that justice and fairness are ambiguous concepts that are hard to translate into mathematical formulas, meaning it is not always easy to program software that guarantees impartiality.

The art of camouflage

The threat posed by facial recognition to certain rights has stirred up concern not only among many groups of activists but also among artists who, over the course of the last decade, have looked for ways to circumvent this technology. Of those leading the way, the most prolific is Adam Harvey, whose work focuses on research and criticism of surveillance. A decade ago, this Berlin-based American gained a certain amount of notoriety with CV Dazzle, a project that leverages fashion as a tool to outwit facial detection mechanisms. The concept is based on the use of make-up and other things such as asymmetrical haircuts that, styled in the right way, confuse algorithms and prevent them from working.

Since 2010, the initiative has branched out into other concepts such as Stealth Wear, a collection inspired by traditional Islamic clothing and the use of drones as a weapon of war, and which uses reflective fabric to prevent tracking by thermal surveillance systems. Another related project is HyperFace, a pattern-generating system still in the prototype phase that, instead of confusing the algorithm by stopping it from recognising faces, satisfies its need for identification by providing it with false faces.

Following a different approach, the artist Zach Blas studies the consequences of this technology on those groups of people subject to the greatest inequalities and those who fall outside of cultural canons. One of his most notorious projects is Facial Weaponization Suite, which creates “collective masks” from the aggregated facial data of people from excluded sectors of society. Fag Face Mask, for example, was generated from images of queer men, but similar objects have been made to represent the invisibilisation of women, the criminalisation of black men, and border surveillance between Mexico and the United States. The resulting masks attempt to represent these identities in a single amorphous head that algorithms are unable to identify.

Another project by Blas related to discriminated groups is Face Cages, in which the artist works using the geometric diagrams generated by facial identification software. The project brings together four queer artists to generate biometric graphics of their own faces, which are then fabricated as three-dimensional metal objects. When in place, the masks resemble cages or meshes of bars, and could be mistaken for some form of medieval torture device. In museum settings, the work is shown with videos of the artists themselves wearing this kind of armour on their faces, although as they are all performance artists, the masks are also used in public interventions and performances.

A third approach worth mentioning is that of the American Sterling Crispin, who between 2013-2015 developed Data Masks, a work that aims not to block facial recognition, but to mirror it. The project is based on reverse engineering, whereby the algorithms themselves create face-like shapes. Taking the results of this process, the artist produces a series of 3D printed masks which he describes as “shadows of human beings as seen by the minds-eye of the machine-organism”. As he explains in the information on the project, the aim of the masks is not to confuse the algorithm, but to hold a mirror up to it, so that the machine works according to its own rules and conventions.

The work of these three artists has a common link: the purpose of the masks is not to hide from the camera, but to confuse it, to trick it. In this sense, their works can be understood as tools for vindication, as weapons of war. This characteristic makes them similar to camouflage, a military tactic – often developed in collaboration with artists – which does not always aim to make the subject disappear, but also to make it difficult for the enemy to see. A classic example is dazzle camouflage painting on ships, which was used during World War I to adorn ships with bold stripes and cubist shapes that would confuse the opposing fleet, who would then be unable to estimate the size or the direction of the vessels. Similarly, the works of Harvey, Blas and Crispin do not aim to make the wearer disappear. Designed for public use in demonstrations, their purpose is to voice a highly visible condemnation of the dominant forms of surveillance and control.

An anti-facial recognition movement

In 2014, journalist Joseph Cox wrote about “the rise of the anti-facial recognition movement”. Looking back, it was perhaps premature to speak of a “movement”, but it can be said that critical design experiments in this area have been multiplying. Some projects continue the work with masks, but the techniques now include jewellery, t-shirts, face projectors, glasses with LED lights, pixelated balaclavas and scarves with faces printed on them, to give but a few examples.

None of these camouflage techniques are effective all of the time. In fact, some of them only work for specific algorithms or for versions of software that existed years ago. What is more, walking around with your face covered or with outlandish garments looks neither comfortable nor elegant, so research on how to thwart facial recognition technology still has some ground to cover. In any case, the initiatives of these artists and activists serve to raise public awareness and interest, something that will ultimately have an impact on public and legislative debate. There are already many governments around the world, both at both the local and state levels, that are proposing to regulate these algorithms. The outcome of these decisions will add extra weight to the ever-fragile balance between security and freedom.

Leave a comment