A workshop organised as part of I+C+i offered Zemos98 an excuse to reflect on the relationship between the media, production and the 2.0 world. This paper provides an interesting analysis of the role of cultural activism – collective, individual or institutional – confronting or working with the media, and of participatory approaches as a means of developing new cultural innovation strategies. Digital tools are crucial, but so are the concepts of collective intelligence, digital identity, and the commons, which have such a strong presence in cultural projects today. Zemos98 invites us to come to terms with a series of key points: the dangers of misinformation, the need for critical thought, and collective responsibility in regard to information.

To complement a micro-workshop that we imparted at CCCB Lab, we decided to release our “source code” in relation to our communication approach. In this article, we explain how we believe that cultural agents should operate online, and we also share some of the ideas that emerged in the course of the micro-workshop.

As with many other small projects that focus on very specific areas within the field of culture, we have had to put up with the effects of the production processes of mainstream media: having an activity ignored in the press because on that particular day some celebrity decides to have tapas in downtown Seville; attracting the media to a press conference because some high-level politician is participating, and being unable to prevent the conversation from being sidetracked to issues that have nothing to do with the work being presented; having to answer questions that are more about the interests of the journalist interviewing you; misinformation, haste, lack of rigour; being dumfounded to discover that a TV station has sent a camera crew to the only activity in which it makes no sense for them to be there: a screening…

And so to avoid playing the role of eternal complainers, last year we decided to tackle the issue from a different perspective. Twelve months ago, we decided to organise what we called a “press conference, 2.0”. The main premises were clear: we would not rely on the institutional context, we would allow anybody to take on the role of a journalist, and we would include off-site participants through video streaming and a specific hashtag on twitter. The result was our best and toughest press conference to date, and it led us to develop and share ideas in an article that we called Beta Communication.

We are now convinced that communication should not be thought of in isolation, by a single department: it is an aspect that cuts right across projects of all types. So perhaps the question that we need to find answers for is the one posed by Edge magazine:

How is the Internet changing our way of feeling, thinking, working and creating?

The socio-cultural context

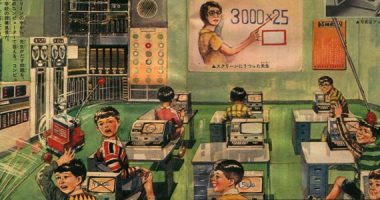

- From atoms to bits. The metaphor proposed by Nicolas Negroponte in Being Digital is still valid. Digital technology has transformed, and continues to transform, notions that cut across our entire lives, affecting our thoughts, feelings, careers, and so on. When VHS technology became widespread, we could start to watch the same film over and over. Now that the Internet has taken hold, people don’t just watch films, they download them, remix them, and put them back into the great multimedia flow.

- Cultural convergence. In 1998, a boy called Dino Ignacio created a website featuring a series of manipulated images entitled “Bert is Evil”, showing the Sesame Street character Bert consorting with figures such as Bin Laden, the Ku Klux Klan, and so on. In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, these images were used in a pro-bin Laden collage put together by an editor in Bangladesh who was not familiar with Sesame Street or the Bert character. The collage was printed and used in mass protests. That hellish image reached CNN and the owners of Sesame Street, who could never have imagined their innocent origins. This curious anecdote, which Henry Jenkins discusses in Convergence Culture, supports his thesis that old media do not disappear, but instead, everything converges in a chaotic, constantly changing media flow.

- Multiple identity. Paul D. Miller aka DJ Spooky explains this notion in his book Rhythm Science: “Jazz great Charles Mingus moved beyond Dubois’s dualities at the beginning of his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, to a form of triple consciousness: ‘In other words, I am three. One man stands forever in the middle, unconcerned, unmoved, watching, waiting to be allowed to express what he sees to the other two. Where Dubois saw duality and Mingus imagined a trinity, I would say that the twenty-first-century self is so fully immersed in and defined by the data that surrounds it, we are entering an era of multiplex consciousness (…). There’s so much information about who you should be or what you should be that you’re left with the option of trying to create a mix of your very self.” And this is what we’re doing when we sequence our selves in asynchronous narratives through social networks: creating multiple identities.

- Collective intelligence. Pierre Levy defined this concept as “the ability of virtual communities to leverage the combined expertise of their members.” In Convergence Culture, Henry Jenkins introduced the idea of “the expert paradigm” into the discussion, explaining that “our traditional assumptions about expertise are breaking down, or at least being transformed, by the more open-ended processes of communication in cyberspace. The expert paradigm requires a bounded body of knowledge, which an individual can master. The types of questions that thrive in a collective intelligence, however, are open ended and profoundly interdisciplinary; they slip and slide across borders and draw on the combined knowledge of a more diverse community.” Peter Walsh critically commented on this in his insightful article “The Withered Paradigm”: “the expert paradigm creates an ‘exterior’ an ‘interior’; there are some people who know things and others who don’t. A collective intelligence, on the other hand, assumes that each person has something to contribute, even if they will only be called upon on an ad hoc basis.” We are all producers and consumers at the same time; we all engage in Do It Yourself (or Do It Together), we are all semi-professionals in some field or other with the help of others… collective intelligence is the key.

- The long tail theory. This idea, developed by Chris Anderson, explains how factors such as reduced storage costs mean that online businesses do not need to focus all their efforts on a small range of products in order to turn a profit. There are two types of markets: one that seeks very high sales of a few products (which is were the mass media would fit in) and another based on the sum or accumulation of low sales of many different products, which can equal or exceed the first. In communication terms, relevance no longer lies in a small number of places, or in impersonal messages and communications; it lies in the sum of conversations that take place in the spaces where users gather.

- The commons. New social interaction between communication and culture is redefining the concept of the public domain. This space of shared, socialised belonging is the commons: a place that we take ideas from, and into which we must put things back in one way or another. The protectionist fixation of royalties management societies, of the obsolete cultural industries and of international intellectual property lobbies are blocking a change that is bound to eventually take place no matter what they do: the realisation that it is possible to combine a cultural model that protects the remuneration of artists but does not criminalize social practices such as remix, appropriation, etc.

This video by Henry Jenkins explains and summarises some of these ideas. In social terms, audiovisual and digital culture skills are not the exclusive property of a particular group: they are skills for the future of all citizens.

Communication and philosophy 2.0

Here will outline what we consider to be the key concepts that come into play in the communication of cultural projects in the network society.

- Critical utopia. The famous video of the “angry German kid” that went viral shows that the Internet is no panacea (read the true story; perhaps we were crazy to call him crazy). Disinformation, as an example of the atavistic problem pertaining to communication, still persists and always will. For this reason, we position ourselves as critical utopians. In other words: we think that the Internet can bring about a better society, but we also think that it is important to be critical, that the “2.0 hype” is misleading, that we cannot generate the sense of constantly being behind the times, that there is a need to provide education for the areas and individuals who remain “outside” of this change…

- Attitude rather than technology. The biggest change taking place is not about technology, it’s about attitude. 2.0 does not come about by installing a technical software, but a mental software. Technology can help us to understand and create more open communication processes, but sometimes the solutions are right under our noses, and they can be as simple as sitting down to talk. We can take advantage of this context to examine our dictates on communication, and to ensure that technology works in our interests. Not all organisations need the same thing.

- In beta. “In beta” became a popular way of referring to the non-definitive versions of many online social media sites when these began to proliferate. It was a means of participating in the creative process, of exposing it to collective intelligence, and of taking advantage of the synergy to attain the longed-for “alpha” version. But people began to realise that this final version would never come. That life itself is like an ongoing draft cobbled together through trial and error, so why would a new, changing medium be any different? Just about nobody has amazing formulas in digital matters, because we’re all playing at becoming professionals in beta mode. Because we all have to come to grips with the fact that the big challenge is not to attain the final version of our idea, work, service, or whatever; the big challenge is to learn to live with an identity that is constantly being challenged and remixed, a multiple identity in beta.

- Transparency. In this context, processes are becoming more important, and results are increasingly relative. Honesty becomes crucial, and entails a greater awareness of oneself, one’s place in the network of agents that operate around us, and so on. But this notion is also full of contradictions, and raises questions such as: What is actually shared in a production process? How does this idea of transparency affect the internal communication of a team of co-workers? How do you publicly explain an error?

- Community. Just having an online presence is not enough, you have to actually “be” there. We are part of communities of shared interests, and we benefit from looking after these communities. It is worth making efforts to integrate and actively involve our most loyal users, because they are usually the ones who help us to improve, who are on the lookout for errors, for changes, for omissions. And because we would be nothing without them.

- Communication is content. In online social media, everybody sells themselves. But everybody also shares knowledge. We have to find a balance that allows us to meet our communication goals while at the same time enriching the commons with our knowledge. Similarly, we have to realise that when we help to disseminate activities with content that interests us, organised by like-minded agents who are part of our community, we are strengthening our connections and the potential reach of both parties.

- Produ-communication. Production processes have to work closely with communication processes. This approach will give greater coherence to the way we project who we are in relation to what we do. Communicating and sharing production processes can provide a great boost to a project. This does not mean that everybody should publicise everything they do, or that everybody else should be forced to read it. As we said above, balance is the key.

- Expanded education. In two senses, we can see how communication and education are inextricably linked in all of our professional roles: internally, because in a context with as many uncertainties and changes as this one we have to rely on others to improve and learn how to use technological tools, to be self-critical, to find coherent solutions… and there’s no better way to do this than to turn to the community that we form part of with our co-workers, and the mutual learning processes that have always taken place informally, and that now have to take on a more central role; and externally, we have to consider that communication is more than just content: it can also be education. Projects, like people, are living organisms. Organisms that learn, that make mistakes, that improve… that educate and are educated, anytime and anywhere. (More on expanded education).

- We, the media. As Dan Gillmor said in his famous book We, the Media, we shouldn’t allow others to tell our story. If anything has made this paradigm change possible, it is the fact that we are becoming our own medium. We choose what we communicate, how we do it, etc.

We hope these reflections have been thought-provoking. Until next time!

Liliana | 16 June 2014

La diversidad de culturas o diversidad cultural se refiere al grado de variación cultural, tanto a nivel mundial como en ciertas áreas, en las que existe interacción de diferentes culturas coexistentes (en pocas palabras diferentes y diversas culturas). Muchos estados y organizaciones consideran que la diversidad de culturas es parte del patrimonio común de la humanidad y tienen políticas o actitudes favorables a ella. Las acciones en favor de la diversidad cultural usualmente comprenden la preservación y promoción de culturas existenteLa Declaración Universal de la UNESCO sobre la Diversidad Cultural, adoptada por UNESCO en noviembre de 2001, se refiere a la diversidad cultural en una amplia variedad de contextos y el proyecto de Convención sobre la Diversidad Cultural elaborado por la Red Internacional de Políticas Culturales prevé la cooperación entre las partes en un número de esos asuntos.

La diversidad cultural refleja la multiplicidad e interacción de las culturas que coexisten en el mundo y que, por ende, forman parte del patrimonio común de la humanidad. Según la UNESCO, la diversidad cultural es “para el género humano, tan necesaria como la diversidad biológica para los organismos vivos”.

Leave a comment