“The sandpit”. Unknown author (c. 1920). Source: pellethepoet.

The scope of the term ‘co-creation’ has broadened to include areas that extend beyond its original sources. In this article we discuss co-creation in connection to production and learning, and examine its potential opportunities at the interface between cultural institutions and different types of groups. We describe some of the projects in which we have explored these two poles and look at the pros and cons of different approaches to co-creation.

Our first co-creation students in the Innovation and Design Thinking Masters thought that co-creation referred to two companies joining forces to create new consumer products. As an example, they suggested a ‘cool’ special offer to sell in supermarkets: a bottle of gin and a bottle of tonic packaged together, keeping the labels of the two different brands. This was an eye-opener for us. We had arrived at co-creation with a different vision. We had given it another meaning, our own. However, as the example of the gin and tonic shows, co-creation has many different origins and possible interpretations. I can’t remember when the word ‘co-creation’ first came up in the workshops we run with CCCB-Lab, I just know that co-creation was suddenly everywhere. And as we’re all co-creating now, it seems useful to ask what each of us means by the term ‘co-creation’, why we use it, and to what ends. In this post we will share our journey through co-creation, in the hope that others may find it useful.

Where we come from: design, social technology and contemporary dance.

At La Mandarina de Newtown we became interested in co-creation because we like the mix of ideas, disciplines and individuals that takes place when people collaborate to create something new. In collaborative processes we learn together and provoke change in the different fields involved – science, art, culture, design, or a relaxed mix of them all. At first we found it useful to turn to the metaphors of participatory design (Schuler), user-centred design, and user-led design. We were also inspired by the collaborative creation practices of the hacker world. A bit later, it was contemporary dance. But let’s take it step by step.

From the design field

The roots of participatory design go way back to designers who assumed that it would be a good idea to include users in the early stages of a design process (for a product, a service, a computer system, …) in order to ensure that the end result met their needs as closely as possible. Participatory design saw itself as a way of ensuring the effective appropriation of a design, and increasing the chances of it being transformed into social and cultural capital by the target community. Many low-tech methods for shared conception and modelling by experts (such as designers) and non-experts were developed. Prototyping is the best known of these. It allows designers to invite groups of people to physically interact with their own ideas –if we can put it this way– given that they express them in the form of objects that then become the means for invention, communication and discussion with the other participants. The prototypes are then gradually fine-tuned, eventually resulting in the definitive system. For example, in Talentlab, a project that we carried out with the CSIC, researchers and teachers co-created prototypes for new educational resources to explain cutting-edge scientific concepts. The results were very varied, precisely because of the interaction among different groups: from role games in which players experience artificial intelligence concepts to videogames that question aspects of space travel.

The prototyping process changes the knowledge, skills and points of view of the participants. And it also affects the types and the quality of their interactions. Learning and transformation apply at both the individual and the collective level. But does learning always take place? If not, what conditions favour it? How is it linked to production? When we investigated the design process, we were struck by the fact that design professionals did not necessarily connect co-creation to learning by the majority of participants. Only designers who were very closely connected to social innovation or meta-design (more on this later), tended to consider learning and its connection to shared production. It was time to look at other environments in which this took place.

Working groups, EXPOLAB Workshop. Photo: Miquel Taverna, CCCB.

Shared technological production

Working at the crossroads of technology and social innovation, we had front-row seats to the evolution of open source projects. This led us to adopt some of its practices in other types of projects that were not strictly software developments. For example, in the project Breakout Escape From the Office! (Forlano,2010), first in New York and then in Barcelona, we used several approaches to the conception and subsequent production of new uses for public space. The specific style of the sessions (Jams, Jellys, Breakouts, Hackathons…) influenced the type of production and integration of code and public space. The co-creation process in these types of projects highlights some significant key aspects of hacker culture. For example, the invitation to work collaboratively involves two factors: firstly, the learning processes of non-experts and of the group as a whole, and the actual production. In other words, participants learn by developing code, and the integration of new arrivals adds new possibilities. But this same process entails a clear distinction between experts and non-experts, and very strict requirements for moving from one category to the other. Generally speaking, this aspect of co-creation needs to be emphasised. It is very useful to include non-experts in the ideas stage, because they can contribute views that are not contaminated by experience. But non-experts have to evolve if they want to remain part of the production stage, otherwise they can slow the project down without making any clear contributions to the quality of the end product. This introduces a hierarchical aspect into group organisation, which ranks the importance of each person within the decision making process, as I already discussed in an earlier article on the spaces of the democratisation of technology (Sangüesa, 2011), which also opened a debate and proposed some very interesting alternatives in regard to the shared group ownership of developments, as can be seen in the creation of creative commons and similar licences.

At this point, it is useful to go back to an overview of co-creation in general. The following quote from Elizabeth Sanders defines co-creation from the perspective of design.

“We define co-creation as any act of collective creativity that is experienced jointly by two or more people. It is a special case of collaboration where the intent is to create something that is not known in advance”Elizabeth Sanders

In response to this invitation to embrace the uncertainty of the unknown –the contingency of future results– we turned to contemporary dance in order to see whether it could provide some additional support.

Uncertainty and dance

Irene Lapuente from the La Mandarina de Newton team has always been involved in dance. When she made the move from classical ballet to contemporary dance, it was a real revelation. The rigid instructions that had controlled her actions as a dancer gave way to other, more open patterns. She could evolve and create, with others, an immaterial and transitory object – choreography – in which it was not necessary to pre-define every movement. Instead of a rigid scheme defined by others, she found that there was scope for her to make her own contribution. (You can see how Irene connects these ideas to learning in her TEDxRamblas talk) Some techniques are part of the ‘improv’ field (Buckwalter), while others (Lepecki) go further and work with systematic processes in order to generate new movements. An example is ‘contact improvisation’, a kind of dance that is open to non-experts. But there is also a certain resistance in professional dancers in terms of the speed and quality of works when non-experts who have not learnt and evolved remain in the group.

Choreographers such as Trisha Brown and Twyla Tharp have done some very important work in the field of co-creation and dance. In Barcelona, dancers like Cecilia Cloacae also work on co-creation strategies in dance. We shouldn’t lose sight of the intention that lies behind these processes: the aim is to generate something, without knowing what it will be like. In this sense, collaborative dance projects have something in common with the generative prototyping that Elizabeth Sanders talks about. Twyla Tharp wrote about individual creativity (Creative Habit) and collaborative creativity (Collaborative Habit), and her ideas can be adapted to co-creation beyond the field of dance.

The hybridisation of methods

The crossovers between co-creation processes in dance and design are also interesting. The role of the group and the role of physical experience in the creation of knowledge are two of the most obvious examples. There is a lot of tacit knowledge in the bodies of dancers, in the prototyped object, in the hands of the prototypists (Sangüesa, Lapuente, 2010), and so on. The body is the repository and the memory of this knowledge. Other analogies refer to the idea of opening up towards the future, or the role of the body in design methodologies such as ‘bodystorming’. Or to fields such as contemporary dance, which use the structure of process as an open scaffolding rather than a rigid prison. The openness of the structure is crucial in creativity and in generative processes such as games (gamestorming). This can be seen in the processes of open code development, which have clear regulations but also allow for a great variability of paths (through the ‘forking’, for example).

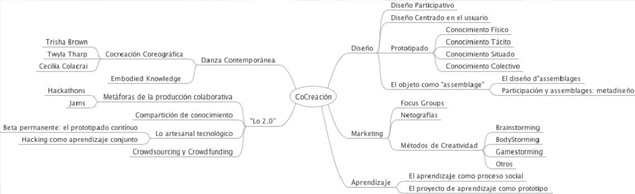

Some of the characteristics and variants of co-creation can be summarised as follows:

- Co-creation as joint conception/brainstorming

- Co-creation as joint production

- Co-creation as part of a collaborative design process (co-design)

- Co-creation as a conception and production process that generates learning

- The tension between production and learning: the integration of non-experts is useful in the conception stage, problematic in the production stage.

- The dialectic between co-creation, horizontal structures and the hierarchy of experts

- Experience, skill and decision-making in projects

But all of this reflects our vision of co-creation. It is not the only one.

Other genealogies

The path that led us to co-creation had also included experience in collaborative social and business innovation projects, in which we used other techniques or adapted the ones we’ve already mentioned. It is useful to compare them to other notions of co-creation in fields in which learning through joint production is less decisive. In marketing, for example, users are asked to contribute their opinions (in their role as future buyers of the idea for a product already thought up by the company) but the group is not expected to learn. Even so, the term co-creation is used. This leads us to wonder how the context in which co-creation takes place influences the values it transmits, the values it adopts, and its scope.

What do we co-create? Objects and processes. Metadesign.

In the scope of design can expand to include immaterial objects, services, processes and organisations, etc. It is thus useful to design processes that in turn generate design processes: to metadesign. Metadesign is inherently participatory and aims to transform the group via learning.

At this point, new challenges come up: representation, ownership of the process and the results, how the decisions that guide the metadesign are made, etc. A group that decides to design itself must face all of these issues. In our first workshops on new collaborative practices for the cultural sector we strove to emphasise this point. We had to work hard to draw attention away from the thing that was then identified with all things collaborative and co-creative: the 2.0 world as just technology. We insisted on the fact that these new tools affect the objectives and organisation of cultural institutions. A door was opening that allowed them to transform their relationship with what they had been calling ‘their’ audience. And to do so, they had to grasp co-creation as the pillar of the collaborative co-design of the core and the interface of the institutions themselves. It was possible to embark on this re-design through co-creation and mutual learning, through prototyping and community involvement. For example, the project we carried out with Kukuxumusu, Kukuxumusu Relocated included an artistic action that consisted of taking the whole company, with all its day-to-day activities, into an art gallery. In other words, all the staff worked in the gallery and became an art object. This process was suggested as a prototype to the people who worked in the company, as a means of reflecting on their working methods. It was the start of a process of co-creation and organisational co-design based on the idea that it is possible to co-create ourselves, to re-design ourselves and create a new organisation that includes us in the process itself. And the participants learnt a great deal about their company and its potential.

Final coda: cultural institutions and co-creation

The way we see it, what these institutions find most disturbing about co-creation is the fact that it is focuses on processes of joint production and activities with audiences, rather than on predefined results. It is clear, for example, that once these premises are accepted new species appear in the institutional ecosystem. For example, by focusing on production processes and co-creation it becomes possible to see libraries as a totally different kind of cultural space –as ‘makerspaces’ where information can be consulted and produced according to the needs that arise during co-creation (3D printers and makerspaces).

Nonetheless, institutions offer an opportunity that seems possible and obvious. Institutions have resources, experience and networks, and staff. They can initiate projects with other groups and contribute skills and experience where required. There are endless possible variations. To give an example, when we carried out the project From Contemplation to Participation and Beyond, the platforms and the technicians at the Tech Museum allowed the project to develop in ways that would not have been possible otherwise. Likewise, the participation of professional designers allowed a high-quality finish. The learning process was common and shared by myriad different people. So there learning and production took place, and different communities were involved, with a certain degree of overlap.

In short, the desire for co-creation can take many different forms, which require greater or lesser involvement by cultural institutions; different opportunities to initiate a project or to bring other agents in, or to join projects proposed by external groups; they can offer their network or their resources, and take the role of “apprentices” in some aspects and “experts” in others. Institutions can take very different paths in their approach to designing a meaningful co-creation strategy.

To back up this idea of a “productive turn”, a “co- turn”, we would like to end with a quote from Vicente Todolí, former Director of the Tate Modern. He is talking about museums, but he could have been referring to other institutions. It gives us some sense of how institutional co-creation could be approached.

“A museum is not the building and not even the collection, even though the DNA of many museums is its works; a museum is an activity for citizens, which can be carried out anywhere.”

Todolí puts the emphasis on the activity. He challenges the usual spaces. He still talks about working “for” rather than “with” citizens. But we like to think that he wouldn’t see co-creation in or of an institution as a process for creating “cultural gin and tonics”. Just imagine if co-creation ended up leading to “gin and tonic institutions”!

References and links

Participatory design

Schuler, D., & Namioka, A. (1993). Participatory design: principles and practices. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

User-centred design

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User-centered_design

Co-creation in design

Elizabeth B.-N. Sanders & Pieter Jan Stappers. (2008) Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign: International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts. Volume 4, Issue 1. Special Issue: Design Participation(‐s)

Co-Creation in technology and social innovation

Breakout! Escape from the office.

Co-Creation and contemporary dance

A. Lepecki (2012). Dance. MIT Press.

Tharp, T.; Reiter, M. (2006).The Creative Habit. Simon & Schuster.

Tharp, T.; Kornbluth, J. (2013).The Collaborative Habit. Simon & Schuster.

Sangüesa, R., Lapuente, I. (2010) Matèria de reflexió, matèria d’exposició. Pensar amb les mans pròpies i dels altres. A Matèria. Noves fronteres de la ciencia, l’art i el pensament. Arts Santa Monica Ciència. Barcelona.

BuckWalter, M. (2010). Composing while dancing. An improviser’s companion. The University of Wisconsin Press.

Metadesign

Giaccardi, E. (2005).”Metadesign as an Emergent Design Culture”. Leonardo, 38:2.

Games

Gray, D; Brown, S; Macanufo, J. (2010). Gamestorming. A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers . O’Reilly Media. ISBN-13: 978-0596804176

Ferran Adrià, “No se puede ser creativo sin una buena organización” Ferran Adrià en Adrià, A; Adrià, F.; Soler, J. (2010). Cómo funciona el Bulli. las ideas, los métodos y la creatividad de Ferran Adrià. Phaidon Press.

Leave a comment