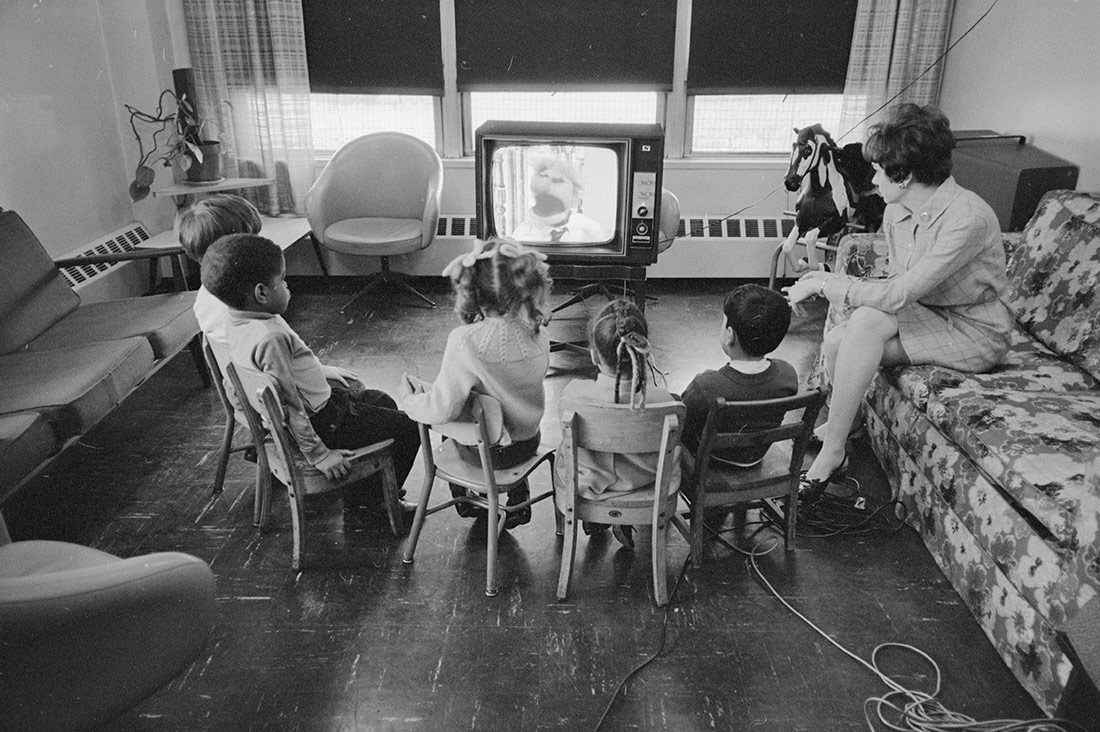

Mother with her son watching television. Saint Louis, Missouri, 1965 | Library of Congress | No known copyright restrictions

Cultural production is constantly on the increase, with an ever wider and more diverse range of offerings. Despite the instant and unlimited access, songs, books and films don’t seem to make an impression like they used to. Immersed in the apathy of scrolling through the algorithm, we dream about regaining our lost sensibility.

I recently read the latest book by a French philosopher and felt infinitely weary. The philosopher analysed the state of culture from a place of deaf pessimism. He threw out cliches left and right, devoid of his previously characteristic discursive elegance. The conclusion was predictable: an anti-intellectual mass made up of “neofeminists” and “anti-racists” is destroying culture with its fanatical hate of ambiguity, hierarchy and beauty in all its forms. Culture, concluded the philosopher, has lost its ability to shape the souls of the future, which are only interested in the banal immediacy of egalitarian slogans and safe spaces. The wonderful ambivalence of the great works of art, of literature with a capital letter, is, to them, anathema.

When we become excessively fatalistic about the current times, I thought as I read the philosopher, we are often just projecting a personal gripe. Other people are able to perceive such gripes quite clearly; they become more and more evident as we grow older and understand less of the world around us. If we let our gripes guide our relationship with the world, we end up succumbing, like the French philosopher, to their facile logic. Before we realise it, we have turned into the old man that yells at clouds.

I just wanted to get that out there and bear it in mind before I admit that for some time now, I have had an unsettling feeling: all cultural products – films, books, audiovisuals of whatever type – seem to me to be exactly the same.

It doesn’t take much thinking to see that the above statement is quite absurd, but even so the feeling remains. I should clarify that I’m not talking about a drop in the quality, the originality or the profundity of cultural products. Quite the contrary. If I pick a book up from the new releases table, I’m sure to find a fresh, bold and lucid voice; I get the feeling that there have never been so many people who know how to write well. It’s the same with films, series and documentaries. There is an incessant and varied flow of exciting new releases; infinite possibilities for entertainment and spiritual nourishment. For those of us who easily succumb to the hype and FOMO whipped up by the cultural industries, the task of keeping up to date is happily never-ending.

I have a friend who refuses to pay for Spotify, even though he earns a good wage, because he likes the ads in between songs. If he knows that sooner or later a loud advert will cut in, he enjoys the music even more intensely. Immediate and unlimited access, meanwhile, cheapens and worsens his listening experience. When he told me about it, I thought he was completely mad, that a long stint in a dark northern country had completely frazzled his brain. But the other day I finished watching a very fine film that took an exquisitely sensitive look at the limits of friendship and the dynamics that perpetuate civil conflicts, and the only thing I felt was slight impatience as I skimmed through the other titles in the catalogue. My brain had already classified the film (“end of friendship/civil war”) and now it wanted something new to chew on.

Woman and children watching television. 1969 | Library of Congress | No known copyright restrictions

My head has become home to a highly efficient bureaucrat who sorts everything into folders and then files them away forever. The bureaucrat appears with his filing cabinet as soon as I start playing the first episode of The Last of Us: “Dystopia/climate change”. He pops out after the first few minutes of Lullaby: “woes of motherhood”. He stops me from enjoying Tár: “cancel culture”. He rapidly neutralises Triangle of Sadness, The White Lotus and The Menu: “ridiculous rich people on holiday”. He sticks on a lot of the labels without hardly looking, yawning while he plays solitaire with his left hand: “book/film/series about #metoo”. “Book/film about threatened rural life”. “Book/article/podcast about the insecurity, self-exploitation and dissatisfaction of millennials”.

I’ll put it another way, then. It’s not so much that all cultural products are the same, as that they all slide over the surface without sinking in – it’s like being at a plentiful and delicious banquet full of tempting dishes from around the world, but with a case of long-covid that has robbed me of my sense of taste.

Last March, the New York Times film critic A. O. Scott walked out after twenty-three years on the job. His explanation was that he didn’t see the point in analysing films that had lost the ability to make an impact. He put his disillusionment down, firstly, to the growth of film franchises, a totalitarian entertainment model that is immune to criticism, and then to the emergence of streaming platforms in the film industry. He said that by financing major directors like Baumbach or Cuarón, and then offering the films online, these platforms have diminished the “cultural presence” of film. As if they were picking up the critic’s baton, the magazine Vulture explained a little while ago why all recent documentaries seem identical, and the New Yorker looked at the consequences of Netflix’s global expansion. The availability and the fact that the algorithm chooses for the viewer engender a kind of passivity; an apathy that is incompatible with the aspirational quality of the seventh art.

The New York Times critic had spent his teenage years watching old Hollywood films in cinemas in Paris. He knew what it was to walk out onto the street with dreamy eyes, drunk on the significance and aesthetic possibilities. It’s tempting to conclude that all he’s yearning after is a feeling of being young again and bearing witness to something mysterious, magical and out of reach. It resembles the disenchantment described by Annie Ernaux in The Years, her generational autobiography of twentieth-century France. The technological advances of the 1980s made the “great home-cinema dream come true”, although the initial excitement rapidly dissolved into an indifferent mansuetude:

Now we were free at last to do everything at home – no need to ask anyone for anything […] The sense of surprise was fading. People forgot there’d been a time when they never thought they’d see the like. But there it was. One saw. And then, nothing.

Perhaps my condition is not the result of Netflix’s malevolent strategies, but rather the echo of a cyclical disenchantment. Or I might have been infected with a generational pessimism about the capacity of culture to leave a mark, both on societies and on people; the dismal feeling that, as creators, we can only hope to contribute a fleeting drop to the tsunami of content that that we surf day and night.

A writer recently pondered the question of what point there will be in reading fiction written by humans once AI is able to write as insightfully and poignantly as people. His conclusion was that no one will be interested in literature written by bots. The beauty of losing yourself in a text is that you get a fleeting glimpse into another human mind, a privileged peek into how they have dealt with envy, love, loss, ambition, inevitable disappointment; and that, during this brief glimpse, you feel a little less alone in the tragic enterprise of life.

As a person who makes his living from writing, this author is desperately invested in thinking this way. And I am right. In times of uncertainty, everyone must erect their own particular pantheon. On the other hand, I suspect that these issues must seem rather less urgent outside the echo chamber and ambitions of people of culture. It’s never too late to look for alternatives. I have a friend who was part of this sphere and has now been rehabilitated: now he only watches old westerns and spends his afternoons pottering in the garden or feeding the squirrels.

As for me, lamentations aside, I’m still hopeful that I may one day recover my lost sensibility. Even people recovering from covid wake up one morning, days or months or years after they first fell ill, and cry with joy when they smell the coffee.

Eulàlia Bullich | 02 May 2023

Crec que insensibilitzen dues coses, una, la individualització del consum del producte i, dos, quan el producte et ve, quan no l’has anat a buscar perquè et respongui alguna pregunta.

Quan pots compartir interessos amb altres, quan tens ganes de compartir lectures, idees… de contrastar-les, de construir pensament, no hi ha aquesta sensació i, quan estàs actiu, quan tens preguntes i neguits i els poses a dialogar amb els productes culturals per analitzar-los, et situes en un procés viu

Eulàlia Bullich | 02 May 2023

Gràcies per l’article!

Leave a comment