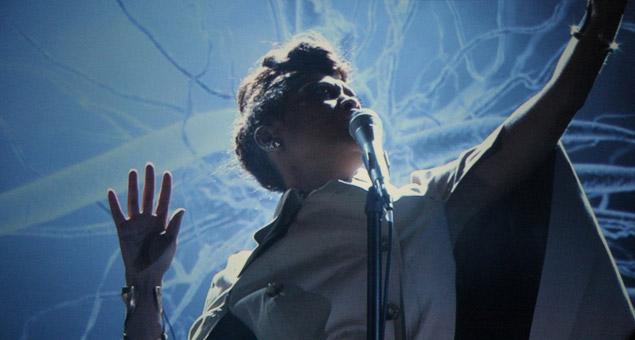

The funk group Parliament, 1976. CC BY-SA. Wikimedia Commons.

The Western view of Africa and of the African diaspora is riddled with clichés such as poverty, segregation, war, and more recently, terrorism. Breaking stereotypes, Afrofuturism is an artistic and cultural movement that has been calling for a new identity for decades through the science fiction and historical fantasy genres. In conjunction with the CCCB exhibition ‘Making Africa’, which takes a new creative approach to the African continent, we look at a genre that recovers pre-colonial roots and projects them onto possible futures.

Flying pyramids and alien pharaohs coexist harmoniously in Afrofuturism, an aesthetic tendency that questions the stereotypes (positive and negative) associated with African identity. Using elements of science fiction, non-Western cosmologies and technology, the genre draws on the past in order to critique the present and imagine alternative futures, all from an Afrocentric cultural perspective.

Although the term was first used by Mark Dery in his 1994 article “Black to the Future”, its expressions can be traced back to the start of the twentieth-century, particularly in the United States. An early instance can be found in the short stories by American civil rights activist and Pan-Africanist W.E.B. Du Bois. In one of his first works of fiction, “Princess Steel” (1908), an African-American sociologist invents a machine that allows him to see across time and space and he discovers an African princess made out of steel who has been kidnapped and separated from her mother: a metaphor of the colonisation and exploitation of Africa.

Like science fiction in general, Afrofuturism expanded after World War II, particularly in the sixties and seventies with authors such as Jewelle Gomez, Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany. Nonetheless, the genre really took off when it found its place in another mass cultural form, American pop music.

The undisputed pioneer of Afrofuturism in the music field is jazz artist Sun Ra, whose artistic persona in the sixties was based on elements from ancient Egypt and science fiction. Sun Ra claimed that he had travelled to Saturn when he was young, and that alien beings there had told him to leave college. Almost his entire repertoire is littered with references to space travel and pre-colonial mythology. Other jazz figures who adopted aspects of Afrofuturism include John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Alice Coltrane.

Sun Ra’s eccentric iconography was picked up in the seventies by funk pioneer George Clinton, who referred to his music as the “home of the extraterrestrial brothers”, made a papier maché spaceship land during his concerts, and recreated a space age driven by African Americans. From the eighties onwards, with the spread of hip hop and electronic music, groups and DJs such as Afrika Bambaataa, Public Enemy, Deltron 3030, and DJ Spooky kept the legacy alive. From 2000 to the present, a multitude of musicians have embraced elements of Afrofuturism, notably Janelle Monáe and Erykah Badu, who we will return to later.A colourful video about California

Muhsinah – Yiy (Music Video). By Phetogo Tshepo Mahasha.

Aliens in an inhuman world

Some theorists have interpreted Afrofuturism’s identification with the extraterrestrial archetype as an allegory of the African diaspora, with the slave trade as a tragic metaphor of alien abduction to other planets. As Kodwo Eshun put it, slavery “means that we have all been living in an alien-nation since the 18th century.” This British-Ghanaian writer argues that the forced uprooting led millions of people to experience the loss of clear, solid points of reference typical of postmodernity, but 300 years before the concept was coined.

American cultural studies teacher and writer Marlo David agrees with this idea of the loss of the modern condition in Afrofuturism. She argues that it reflects the failure of the white Western humanist project, given that the slave trade, colonisation, and racism made this utopia and its values unacceptable to the African population. Against this backdrop, science fiction offers new possible subjectivities such as that of the alien and the android, which can be both corporeal and incorporeal, human and post-human.

From ‘black pride’ to a fluid identity

Afrofuturism is framed within the field of African identity, which was shaped gradually over decades, particularly in the second half of the twentieth century. A good example is the changing meaning of the term “black”, which was a derogatory term for any non-white in colonial cities, but began to be used with positive connotations all over the world from the sixties onwards in parallel with the fight for civil rights and decolonisation processes. Being black ceased to be an insult, and became something to be proud of. In the late eighties, however, academics such as Stuart Hall questioned the adjective, because it meant assigning people an essential identity based only on skin colour, which is a characteristic without a biological basis.

Afrofuturism clearly reflects this evolving identity, given that in the words of Daylenne English and Alvin Kim it imagines a “less constrained black subjectivity in the future and (…) a profound critique of current social, racial and economic orders.” Their perspective coincides with Marlo David’s idea that in a “post-human universe governed by zeroes and ones, the body ceases to matter, thereby fracturing and finally dissolving ties to a racialized subjectivity”. Adding a different perspective, Ytasha Womack points out that one of the roles of Afrofuturism is to dismantle the idea of “race as technology”, which is to say the construction of the myth of biological differences among humans as a tool at the service of European colonialism and American slavery.

Erykah Badu, at Umbria Jazz, 2012. CC BY-SA SunOfErat. Wikipedia.

Erykah Badu: “Analog girl in a digital world”

A good example of all of the above is the case of neo-soul artist Erykah Badu, a key figure in today’s Afrofuturism. As the name suggests, neo-soul is a music genre that recovers the legacy of 1960s and 1970s American soul and, in a sense, its cultural context too: the civil rights struggle and the idealisation of African-American community life. However, Badu combines the recovery of the past with a constant questioning and reinvention of her identity.

Both aspects are apparent in her two latest releases, New Amerykah Part One (2008) and New Amerykah Part Two (2010). The first is full of social criticism and references to the problems of the African-American community in the United States today, against the backdrop of the dream of a black humanism. The second, in which the lyrics revolve around personal relations, explores the private realm and identity, rather than the social dimension, and plays with the iconography of a robotic Erykah Badu living in a dream-like fantasy world. Together, the two albums create a sound diptych which perfectly illustrates the flexible coexistence between the past and the future that characterises Afrofuturism, which, instead of offering the hope for a better future, cerates an identity outside of a specific time and space, and gives a leading role to those who did not have one.

Ruth | 09 June 2020

Genial (L) Una corriente de la que debería hablarse mucho más.

Pedro Petrucci | 31 August 2022

Excelente texto, muy claro y bien estructurado. Gracias por los referentes en música y en literatura afro futurista

Así se vivirá el AFROFUTURISMO en el Negro Fest 2023 – NegroFest | 09 May 2023

[…] Fuente 1 – Fuente 2 […]

Leave a comment