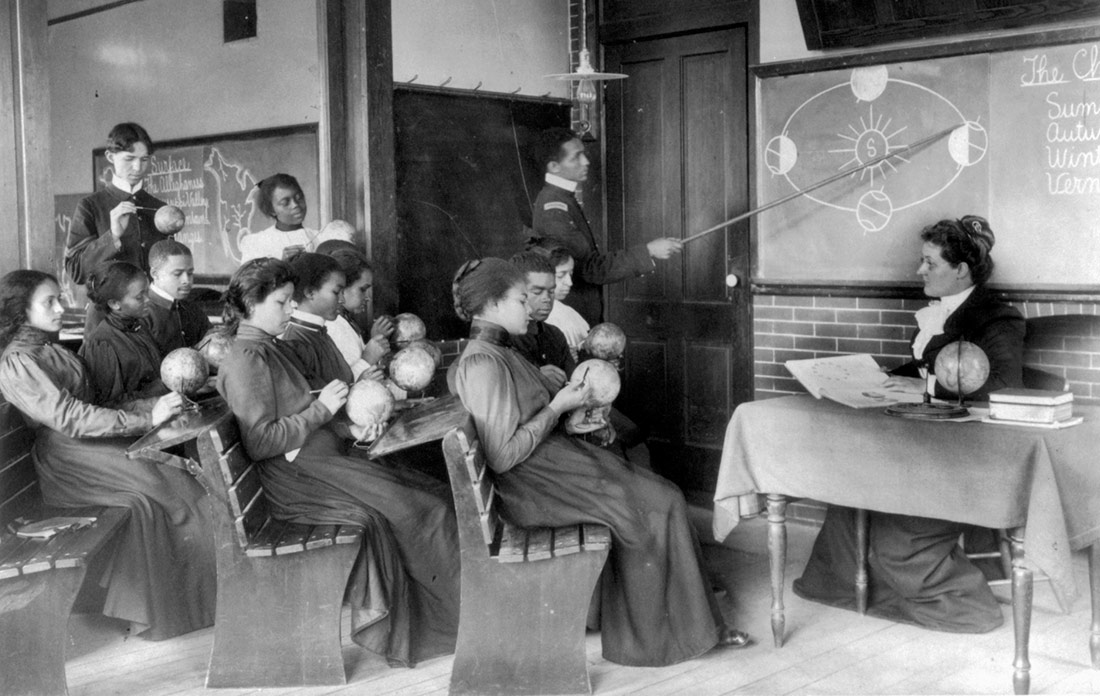

A class in mathematical geography studying earth’s rotation around the sun, Hampton Institute. Hampton Virginia, 1899 | Frances Benjamin Johnston, Library of Congress | Public Domain

In the late 1990s, Microsoft creator Bill Gates and an Australian history teacher, David Christian, launched a free online project to teach high school pupils history. Not in the way they had studied this subject up until then, but by merging disciplines: astronomy, physics, biology, evolution and social sciences. This is the genesis of Big History, a subject that is taught in secondary schools around the planet, for which even universities like Yale have a MOOC, and that has as many defenders as it does detractors.

“Big History is the first class I can actually say I’ve enjoyed history in”; “I really enjoy the discussion that we have”; “it’s the history of everything, on a very broad scale”. For a teenager to leave a history class so motivated is not that usual. Those of us with greying hair can all remember the never-ending hours packed with facts, dates, names and disconnected data in biology, history of art, literature or physics classes that we swallowed before the exam and then, inevitably, forgot. We went through secondary school without having joined the dots that would have allowed us to form a global image.

This is what makes the promise made by David Christian, an Australian History lecturer at Macquarie University, so attractive; “By the end of this course, you’ll have surveyed the whole history of the universe, and you’ll know how you fit into it”, he says.

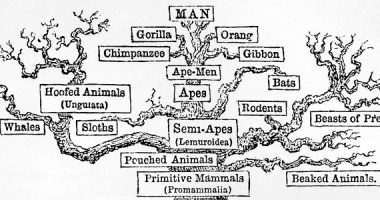

Four decades ago, Christian was tired of seeing bored students in history classes; he didn’t understand why the hard sciences were taught apart from the social sciences. So he began to blur boundaries between subjects to create a new one that blends knowledge of history, but also of biology, chemistry, astronomy and other fields. This was the start of Big History, which sets out to explain “the integrated history of the cosmos, the Earth, life and humankind using scientific methods and the best empirical evidence available”. A Big History of everything that begins with the birth of time and the universe, 13,800 million years ago, and narrates everything that came afterwards. Including us, humans.

That it has become a global movement surely has a lot to do with the fact that Bill Gates took an interest in the project in 1998, when he heard a series of Christian’s talks. “Those videos made me think that I’d have liked to have studied Big History when I was young, because it would have allowed me to shape everything we learned at school and the reading that followed. In particular—says Gates—it positions science in an interesting historical context and explains how to apply it to many contemporary problems.”

Together, Gates—who invested $10 million of his personal fortune in the project—and Christian created a team to achieve their goal: for Big History to reach as many students as possible all over the planet; instead of studying separate periods, they learn narratives spanning millions of years.

For example, a class about the Big Bang begins with a theocentric view of the universe, introduces Ptolemy and his conception of the Earth, then reviews the heliocentric versions of thinkers like Copernicus and Galileo, before coming to the Hubble Space Telescope and the expanding universe. When talking about how stars were formed, they study Einstein and the hydrogen bomb; and, if they explore the origin of life, Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey appear.

This initiative, which has replaced all the books with highly attractive online materials, currently has millions of enthusiasts and advocates worldwide. It is taught in institutes in the United States, Australia, South Korea and the Netherlands. There are MOOCs at universities, the Khan Academy includes it on its syllabus, as does the University of Amsterdam and even Yale. However, this rather epic way of explaining history has also gained detractors and critics.

The union of knowledge

The underlying idea of Big History is to achieve a kind of consilience, a concept that refers to the unity of knowledge dreamt of by many scientists and thinkers, such as the Annales School, a group of French historians in the early twentieth century who defended the exploration of history at multiple scales of space and time. Christian recognizes the enormous influence that this School has had on him. He takes this idea and divides history into eight thresholds. The first is the Big Bang, another is the origin of Homo sapiens, supposing the appearance of the powerful force of collective learning, and another is the emergence of agriculture.

“It’s a story in which humans play an astonishing and creative role, but it also contains warnings: collective learning is a very powerful force and it is not clear that we humans are in charge of it”, says this Australian in a TED talk that has over 11 million views and in which he manages to explain the history of the world in 18 minutes. “We believe that Big History will be a vital intellectual tool for new generations as they face the challenges and the opportunities ahead of them”, says Christian.

For Marco Madella, ICREA research professor in the Humanities Department of the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Barcelona, “Big History allows us to extend the scale with which we regard our species, life on this planet”. For this researcher, the appeal of this approach is that not only the perspective but also the methodology is broader and more transversal.

Transversality, the crossover of disciplines, is one of the most attractive aspects of this project. “Crossing boundaries, domains that are considered complete but have gaps, is extremely interesting, and this is what I try to do in my work”, says Saskia Sassen, Professor of Sociology at Columbia University, an opinion shared by Ricard Solé, ICREA research professor at the UPF. “The most interesting research happens where disciplines overlap, so it would be fantastic to be able to transfer this to education.”

“This goal of unifying all the knowledge of humanity was attempted by the eighteenth century Enlightenment and more recently by Edward O. Wilson (US biologist), who was the first to call for a return to a humanistic, scientific enlightenment; Jared Diamond has been trying for years to integrate biology and history, not to mention Yuval Harari”, says Juan Luis Arsuaga, co-director of Atapuerca Archaeological Site.

“Big History uses the Anglo-Saxon concept of story, telling a tale. Its proponents speak of creating a new myth, in the sense of narrating the origins of everything, of the world, of humanity”, explains Xavier Roqué, lecturer at the History of Science Centre (CEHIC) of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and member of the Philosophy Department.

A new creation myth

“It is very tempting to try to tell epic stories at the grand scale, stories with a narrative hook, and to use this appeal to change the way we explain history. At universities, too, teachers of different disciplines work together but without trying to produce a single, unique storyline.” Because, the physicist and historian Xavier Roqué continues, “history is so complex and diverse, and there are so many approaches that trying to create a master narrative is doomed to failure. There is no single truth, and Big History is not transparent as to its intentions, agenda and ideology”.

For some critics of the concept of Big History, one of the main problems is the loss of nuance. For Roqué, “it is a tempting idea to integrate a scientific view into how we study historical events, but the problem is that, the way history is constructed, it is incredibly rich. I don’t know to what extent we have to sacrifice the detail of how the various historical events occur.”

“History is continually being redefined, raising new issues that previous generations didn’t know about. Big History homogenizes humanity, which appears at the end of the history of the universe. From this viewpoint, human being is one. But the differences, which on that scale may be irrelevant, on the scale on which we live are crucial”, maintains Roqué.

Loss of voices and nuances

“The Big Bang narrative is presented as absolute truth, when the truth is that, from the Big Bang to the present moment, there are all manner of scientific controversies, debates and disagreements about what happened and how that don’t appear in the narrative but do help to foster critical capacity. The seductive aesthetic of Big History has an anesthetizing effect; it doesn’t prepare kids to develop a critical mindset with which to face the challenges of the future”, says Clara Florensa, physicist, biologist and science historian, and lecturer at the Gimbernat University Schools, attached to the UAB.

By telling a story designed to thrill, with a strong plot and a seductive treatment, Big History presents a very powerful narrative in which, if the story of the cosmos lasted 18 minutes, the chapter for humans would take just a few seconds. “Who decides what is explained in those seconds? Who values the human stories that are told?” asks Roqué.

How to revolutionize history classes

Despite the weak points than many historians find in Big History, it is clear that it manages to motivate kids, still a pending issue in history classes (and many others, something that the Escola Nova 21 movement is now trying to remedy), but one which, slowly, is changing. For Madella, one of the problems of how history is traditionally taught in many cases is that it falls into the trap of a “certain particularism”, where the important thing is to know a date, or a battle, “but the global image escapes us—why these things happen”. Here, Big History “offers a global vision that helps children to learn not just facts, but also the broader dynamics of the planet”.

For Solé, an interesting way of harnessing the appeal of Big History without sacrificing the depth of themes, the diversity of visions, a critical approach and nuance would be to ask “‘What if…? What if Hitler hadn’t died? It might seem like a game, but it forces you to know the real story, to have a deep knowledge of the context and all the actors involved, and, above all, to think.”

“The revolution in education is not teaching Big History, it’s applying a view of history that introduces controversy and disagreement, and that breaks down the processes of consensus building—inseparable from the historical context in which they occur—because scientific practice is basically that. It is much more enriching to present kids with different viewpoints, what happens behind the scenes in the production of scientific knowledge, and to foster in them a spirit of inquiry and criticism than to give them a version carved in stone that they don’t even have to think about. We have to show them that the process is also important, and this is, ultimately, what is lost with Big History”, says Florensa.

Leave a comment