Washington Equal Suffrage Association put up posters. Seattle, 1910 | Wikimedia Commons | Public domain

Politics has stopped raising its voice. The new propaganda no longer shouts at us, it caresses us. A few decades ago, Neil Postman warned that we would soon be amusing ourselves to death – today, Generative AI has arrived to finish us off with one big final laugh. The ability to replicate any style in any format has turned social media platforms into minefields where all content can carry a political message in disguise.

The Boy and the Heron join the army

Our devices are often inundated with trending social media content that follows the same aesthetic style, conceptual approach or narrative thread. The case in point begins with the release of a new ChatGPT feature. On Tuesday 25 March 2025, OpenAI’s GPT-4o model was rolled out, offering text-to-image capabilities. This is something that had already been around for a few years, so where was the change? The difference was in the multimodal approach that makes it possible to combine text and images to generate content using natural, conversational language, maintaining the structure and theme of the original image while changing specific details such as a character, the style of the photograph or the camera angle. This new form of interaction opened the door to the creation and remixing of all kinds of images with very high levels of fidelity, coherence and aesthetics, making it possible, for example, to apply a specific style to an image while keeping the original structure, characters and colours.

After the release of this new feature, social media quickly became full of images remixed in a whole array of very different styles, until one began to stand out above the rest. A post went viral on X where a man gave his wife images of the two of them reworked in the style of Japanese animators Studio Ghibli – one of the most well-known studios in modern animation. People had been replicating this particular style since the beginning of the Generative AI revolution in 2022, but this post was a definite game changer. In a matter of hours, the networks were flooded with “Ghiblified” images, creating a huge trend. And the new propaganda loves trends.

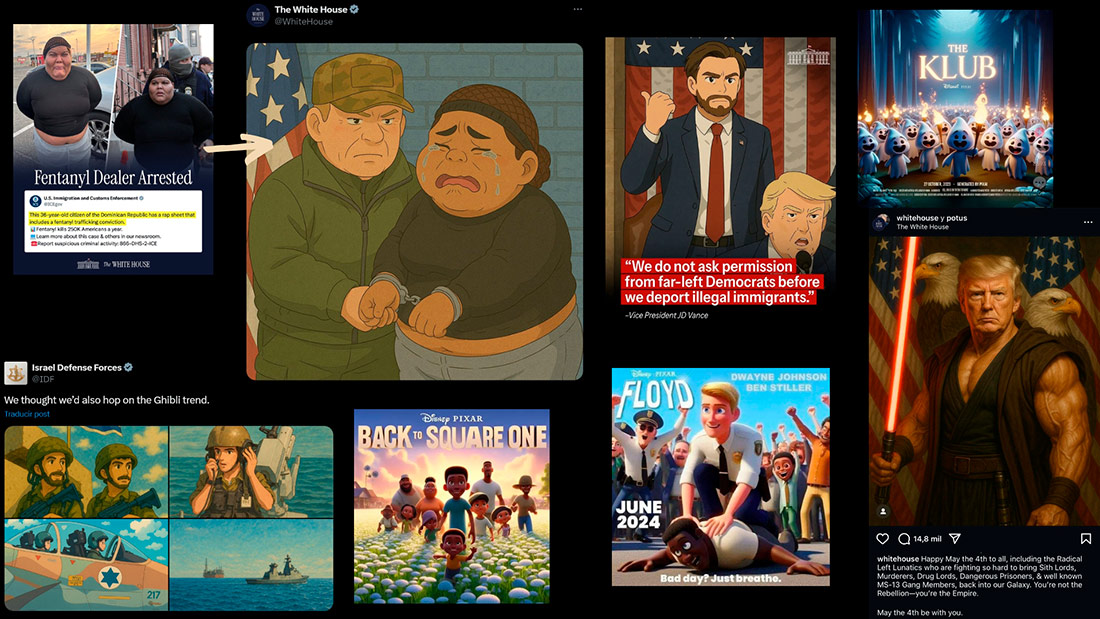

Political parties, organisations and leaders quickly took advantage of this craze around the Ghibli look to generate and share their own images. A few days later, the White House’s official account published a Ghiblified image of the arrest of a fentanyl trafficker. Three days later, the Israel Defence Forces’ account published four images of Israeli soldiers in the same style. These are just two examples of what was a veritable wave of Ghibli-style populist content; from European far-right leaders to the restyling of iconic moments from America’s right-wing, such as the Trump shooting in Pennsylvania. To understand the smooth effectiveness of this machinery that harnesses trends to push political messages, we must look at three dimensions: the aesthetic, the ideological and the algorithmic.

Examples of AI-generated right-wing propaganda in the styles of Studio Ghibli, Pixar and Star Wars.

A Trojan horse with neon lights

Style is one of the keys to the danger of this new form of propaganda. In a context in which any well-known aesthetic is replicable, the one we ultimately choose is of paramount importance. Take Studio Ghibli – the rounded lines, pastel colours and characteristic faces evoke an imagined world of childhood, innocence and peaceful community, values the Japanese studio has promoted in all its films. But what happens when the form and content don’t match? The use of these light-hearted, friendly and aesthetically pleasing styles is an invitation to lower our guard. Critical thinking is disarmed even before the ideology takes aim, and our focus shifts from the content to the packaging.

The Studio Ghibli case was neither the first nor will it be the last in the new propaganda machine driven by generative AI. Almost a year ago, a Pixar-inspired trend went viral and was quickly used to spread political content packaged in seemingly innocent aesthetics. In the US it was used to share far-right racist content, while in Europe it became a weapon to attack migrants. In both cases the modus operandi was the same – take advantage of the design potential of the new generative tools to camouflage messages that would otherwise set off all the alarm bells or be moderated off social media. However, if aesthetics act as a Trojan horse for ideology, algorithms are the wheels that drive the wooden behemoth forward.

The propagandistic mechanism works particularly well because it integrates within the participatory culture that underpins social media. Users do not simply consume an image; they modify it, transform it, share it and reappropriate it. These iterative processes trigger engagement with similar content and amplify it through the opaque prioritisation of the algorithms that mediate social media content. The result is a new kind of propaganda that acts by repetition. It is not about offering a convincingly strong message, but about hijacking trends to introduce content that pushes hackneyed populist arguments, with aesthetics that lower the barrier of entry to participate in these discourses.

The latest element added to this mix is another pillar of modern digital culture: memes and humour. AI-generated and remixed images follow a memetic logic that is particularly ingrained in social media and that draws from classic propaganda, adapting it to new socio-cultural contexts. Generative AI supercharges the potential to create memes – a form that has been extensively studied for the purpose of spreading political messages – by adding an extra layer of glitter that makes it difficult to identify the ideology behind the content. Humour acts as a shield and a smokescreen: it diffuses responsibility while enhancing the viral potential of the content it protects. These three dimensions – the aesthetic, the ideological and the algorithmic – are what set the propaganda machinery in motion every time a social media trend emerges to instrumentalise what we find endearing and humorous.

Epilogue: the audacity to remain

The Studio Ghibli trend has been and gone, but the underlying mechanism is here to stay. To dismantle the propaganda machinery, there is nothing better than experimenting, creating and remixing to discover its inner workings and keep us from falling back into the trap of aesthetics. At a higher level, the social media platforms often act as a sort of Wild West for regulation, ethics and morality, where seemingly anything goes if it is wrapped in humour or a cute aesthetic. The collective challenge is enormous: to foster critical thinking and AI literacy while addressing the issues of authorship, responsibility, rights and sustainability raised by these new tools. As in The Boy and the Heron, hope lives not in perfect worlds, but in the imperfect ones that we can still change.

Leave a comment