Kids making books of comic strips. San Augustine, Texas, 1939 | Russell Lee, Library of Congress | Public domain

The stories and characters of Chris Ware have shaped the artistic careers of countless authors. Gabri Molist recounts how he discovered Ware during his formative years and how the American artist’s style influenced his own professional direction. From there, Molist muses on experimentation in graphic storytelling and the craft of drawing comics.

Sequence 1

“Characters’ conflicts create fiction,” I think to myself as I begin typing the lines of this text, glancing distractedly at the space that I call my workshop – two tables, a second-hand armchair, a small microwave and a bookcase are what make up this small space in the Schaarbeek neighbourhood of Brussels. I stare at the bookshelf, where my eyes pick out an old, worn copy of Building Stories. It’s the comic book in a box in which Chris Ware presents fourteen stories featuring a woman who spends three decades living in an apartment block in the Oak Parks neighbourhood on the outskirts of Chicago. My mind leaves Brussels, where I’m writing, and takes me to Chicago. Or what I think is Chicago, since it’s a city I only know through Chris Ware’s comics. Who lives there? What must life be like? What do its inhabitants dream of? What conflicts do they have?

Characters’ conflicts create fiction. That’s what they say. Chris Ware’s characters overrun my mental Chicago: Rusty Brown, Jimmy Corrigan, Jason Lint and the female protagonist of Building Stories. They are introverted people, normal people, but with complex personalities. Their narrative arcs all follow the same direction: mundane, sometimes sad, with touches of humour, far removed from the rigid narrative arcs of mainstream fiction. In a clear attempt to imitate the rhythms of human life, I feel that Chris Ware’s characters depict inconsequential lives, empty of heroic or remarkable events. Lives, however, that are interconnected – between workers and students at the same high school (Rusty Brown), between residents of the same apartment block (Building Stories) or between members of the same family (Jimmy Corrigan).

Still in my mental Chicago, I tell myself that I could stay here a little longer, as I reflect on how Chris Ware has featured in my personal life and how the influence of his work, but also his life, shaped my early years as an artist, as if he were a character from a past life. Similarly, I think of my past self as just another character. Encounters and re-encounters. Isn’t this an example of a mundane life that goes by, but that always appears interconnected?

Sequence 2

If you are a cartoonist, illustrator or comic book fan, I think this is a pertinent question: do you remember the first time Chris Ware came into your life? My answer: the arrival of Chris Ware in my life could be described as an explosion. I think I remember the moment. I was about twenty-one at the time and studying at the Massana School in Barcelona. I wanted to be an illustrator – to make posters for bands I admired, to draw ideas from critics and journalists in magazines… oh, young dreams! During an exchange programme in Belgium in 2014, I discovered a type of comic that I had never seen before – the work of Belgian artists such as Brecht Evens, Olivier Schrauwen, Brecht Vandenbroucke and Nina Van Denbempt turned my (fragile) professional plans upside down. If what they were doing in Belgium was comic, then I wanted to be a comic artist!

When I returned to Barcelona, hungry for more artists who could follow the trail of that Belgian star, two people saved me from my post-Erasmus blues: Arnal Ballester and Cristina Daura. One was my final research project tutor and the other is an illustrator who was then working on a comic (which I think, unfortunately, never saw the light of day) with a panel layout that had never been seen before. While I was telling Arnal that I wanted to do research on formal experimentation in graphic narrative, and interviewed Cristina for the school magazine, the two of them pointed me in the same direction – Chris Ware. Kapow!

Sequence 3

I begin writing this text two days after the opening of the exhibition Drawing is Thinking at the CCCB, dedicated to the American comic book artist. Now in Brussels, I look covetously at the social media posts, videos and stories about the opening and the talk between the artist and the writer Laura Fernández. One Instagram post, however, stands out from the rest. Chris Ware in the garden of the Finestres bookshop with three other comic book legends: Craig Thompson, Richard McGuire and Max. My mind travels quickly – to Ghent, Belgium, 2017. I’m drawing in my school workshop while I listen to a filmed talk by Max. The Catalan cartoonist is giving a talk to some students at Madrid’s Complutense University in 2010. Towards the end of the interview, a student asks him to talk about his relationship with Chris Ware, and Max responds with a wonderful anecdote. Apparently, when Max asked Chris Ware if he wanted to publish some pages in Spain (for the first time) for the magazine Nosotros Somos Los Muertos, he said yes. But he had one question: “Who will letter my stories?” Max replied that he would do it himself, and Ware answered, “I’ll send you the nibs I use, so you can do it the same way.” A few days later, the transatlantic package arrived at Max’s house. Max opened the package and found an envelope of nibs… that was completely empty.

Sequence 4

In an interview from 2001, Marnie Ware, Chris Ware’s wife, said: “It’s funny, because his characters often look like the same character dressed up differently.” [1] What if it were true? What if, behind each of Chris Ware’s iconic characters (Jimmy Corrigan, Rusty Brown, Jason Lint, etc.), there were the same hominid? A chubby, bald, pink baby?[2] And what if all these characters came from an even more embryonic hominid? It would be logical to deduce that all of Chris Ware’s characters came from that same place. But what if (what if!) all these Chris Wareian characters came from higher up (or lower down?). I imagine a pink ball emitting comic characters for all those cartoonists who request them. Would it act as a kind of oracle that cartoonists could visit when they needed? Where on the planet would it be?

Sequence 5

For ten years, I’ve been travelling from Barcelona to Brussels with a large red suitcase. Two weeks ago, with great sadness, I decided to lay to rest this suitcase after so many comings and goings. Building Stories was the largest and heaviest book the red suitcase had ever carried.

Sequence 6

“All the unhappiness of man stems from one thing only: that he is incapable of staying quietly in his room.”[3] A couple of months ago, I read this quote by the thinker Blaise Pascal in a book by Paul Auster. I think Chris Ware knows this quote as well as any other cartoonist. From his studio in Chicago, I imagine Ware doing everything he can not to leave this interior space where, week after week, he creates pages and pages of books that explore the chronic unhappiness of humankind.

Sequence 7

Sequence 8

Winter 2024. A not-so-young-anymore Gabri Molist spies on the famous cartoonist’s studio via a YouTube video. The studio is in an attic. Chris Ware works in the attic of his home. As he watches the video with interest, the not-so-young-anymore Gabri thinks about something Ware himself once said: “Cartoonists especially tend to be either attic workers or basement workers, and I’ve had this theory for years that those who work in the basement had trouble with their moms and those who work in the attics had trouble with their dads.”[4]

Back to the video: Chris Ware speaks to the camera and says that each page takes him forty hours of work. Gabri cringes as he looks at the board in his workshop where he has just drawn a page in about three hours: “Not so good,” he thinks as he looks for details here and there that he could add to reach the thirty-seven hours that separate his modest page from the average page by the American cartoonist.

At another point in the video, while Chris Ware plays the piano, the camera pans across a cupboard full of old toys, including Peanuts and Gasoline Alley action figures. The not-so-young-anymore Gabri thinks: perhaps, to learn something about the craft of drawing, I should turn into one of those figures to spy on the master. Becoming a kind of surveillance camera with legs in the shape of a comic book character is the solution to all my personal and professional woes.

Sequence 9

The matter of the appearance and disappearance of the comic character and their role in the narrative framework is one of the questions I ask myself when I draw comics. How does a comic work when the character is absent or can only be sensed? What remains of the character when we erase them from the scene and only the speech bubble is left? Does the speech bubble suspended inside a panel mean that we are dealing with a ghost? I think Ware is an artist who has asked himself similar questions. So, if I ever got to interview Chris Ware, I think my first question would be this:

(I don’t know, to be honest. I’d probably get very nervous and say something stupid. Sorry, Chris.)

Sequence 10

In an interview, Ware explains to the interviewer[5] that, in the 1920s, there was a man who became famous for reading comics on the WGN radio station in Chicago. He did it for the children who couldn’t read them. Over the airwaves, this man, Walter Drew, played Uncle Walt, one of the characters in Gasoline Alley, a comic strip drawn by Frank King, which was very popular at the time (and a source of inspiration for Chris Ware). It turns out that Walter Drew was, in fact, Uncle Walt – Mr Drew was Frank King’s brother-in-law.

Comics are currently experiencing an explosion and expansion: the traditional serialised comic books have coexisted for years with “graphic novels,” which were joined by webcomics about fifteen years ago. The explosion continues with the recent boom in fanzines, small press and self-publishing, but also as comics move into exhibition spaces: installations by artists such as Francesc Ruiz and Stefanie Leinhos are opening up new spaces for mediation and exhibition for comics, as are comic readings – performative readings of comics by cartoonists. Ware reminds us that the further we move towards the unknown, the more we should look at the work of those cartoonists (Frank King, George Herriman, even Schulz) who sparked the original explosion, in a context where the language of comics still consisted of a short story and primary visual and narrative structures.

Sequence 11

Thank you, Chris Ware, for making me appreciate (making us appreciate?) comics in the way that I believe (in my humble interpretation) you appreciate them – deeply and honestly, but with humour.

Sequence 12

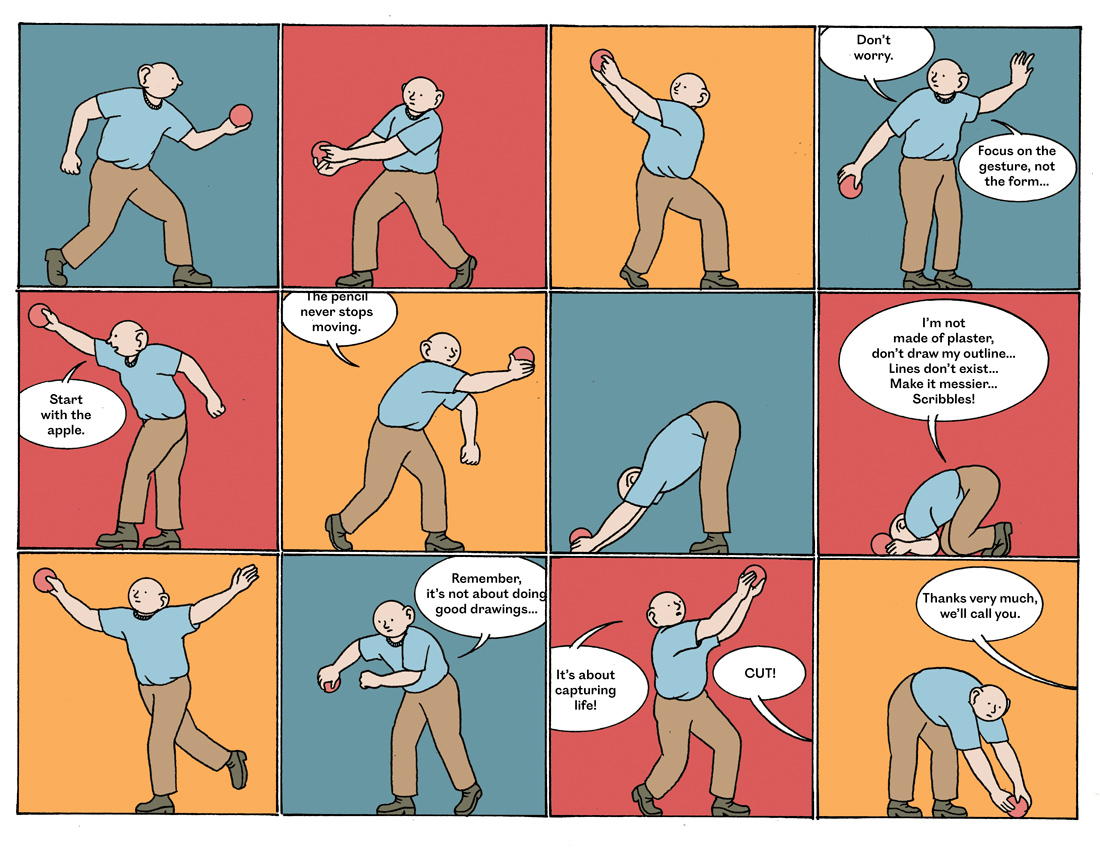

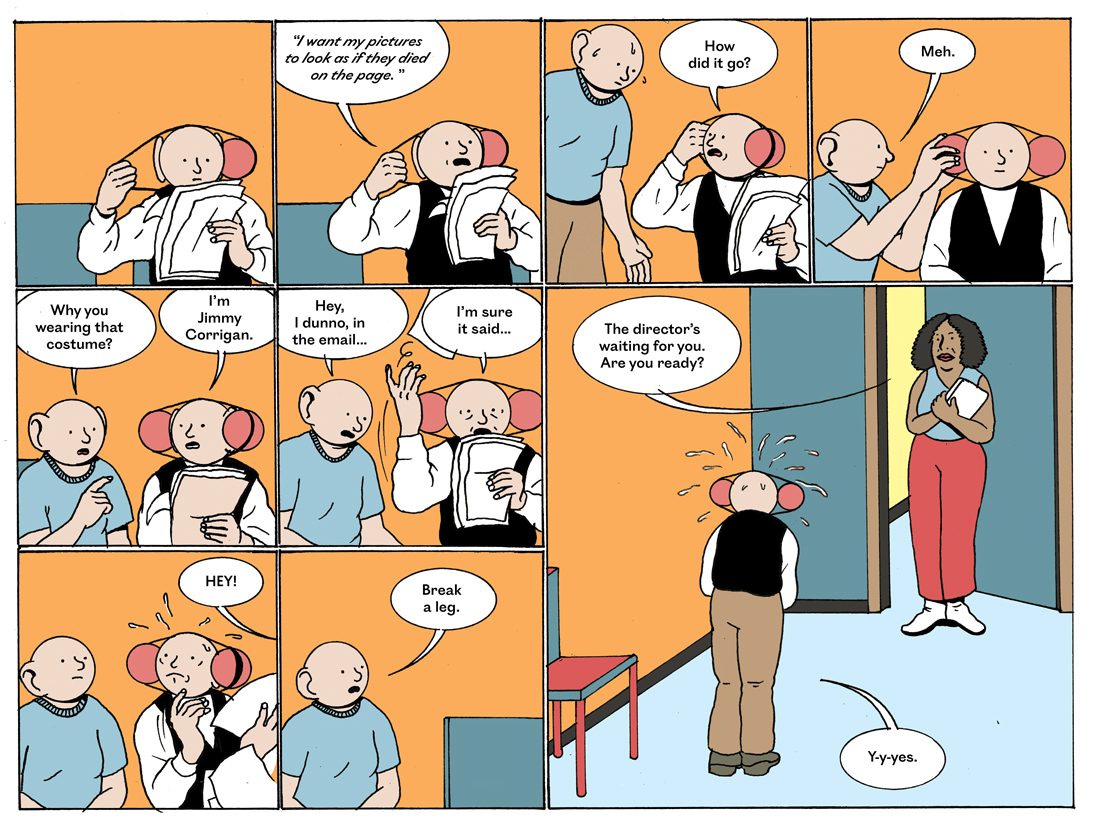

Some other words from the interview with Marnie Ware come to mind: “Inking is kind of a relief he [Chris Ware] gets. He makes a lot of phone calls; he talks while he’s inking. He’s like a teenage girl. (…) He has many friends that he’s never met, and he’s known them for years exclusively through the telephone.”[6] I imagine him talking to other comic book characters, characters created by other artists. If you’re reading this and you’re an artist, put your favourite characters here. I think he could talk to Hey and Hei, a pair of identical characters I’ve been drawing in my comics for a few years now. They’re also round and bald. I don’t know if they’re pink, but why not? I imagine Ware on the phone, talking to both of them at the same time: “I’m thinking about a new comic, and I was thinking of you for one of the roles. But first, you’ll have to come to a little casting. I’ve seen that so far, you’ve only acted for a certain G. Molist, so I want to see if you have the right profile. I’ll put you in touch with the casting director.” Hey and Hei, from Hotel Penumbra, tired of the slow, trudging rhythm of the resort, look at each other and say, “What if we go for it?”

Sequence 13

Sequence 14

Now that I’ve finished this text, still in my mental Chicago, I go back to the idea that Chris Ware is a cartoonist, but also a comic character. “Mr. Brown, the human clown. This is how the kids call him,” thinks Chris Ware, art teacher at the school where W.K. Brown works, as he offers a cigarette to the shy, pathetic character from the latest comic published by the American cartoonist.[7] Back in the book, Chris Ware, the art teacher, looks again at one of the characters in Rusty Brown and says to himself: “And if I was gonna draw him, I guess that’s how I’d do it.”

I think about the possibility of Chris Ware drawing himself again in the future as another character in his stories. This time he could be a music teacher. He who has always preached that comics have an inner music that the artist must know how to detect and potentiate. A rhetorical question that the writer Catherine Taylor asks in her book Image Text Music comes to mind: “If the conjugal relationship of image and text produces a kind of music, what is it? Not just an erotic reverie but an eroticized way of reading and looking?”[8] It would be fantastic to attend the classes where Chris Ware, the music teacher, answers these questions.

With this hope in mind, I return from Chicago to my studio in Schaarbeek. The characters and their fictions. Re-encounters. Time will tell.

[1] Brownstein, C. (2001). “Kiss and Tell: Living with Chris, Dan, Gilbert, and Adrian”, Comics Journal núm. 234.

[2] Tolentino, N. (1998). “Chris Ware of the ACME Novelty Library”, Bunnyhop no. 9.

[3] “La infelicidad del hombre se basa en una sola cosa: que es incapaz de quedarse quieto en una habitación.” Auster, P. (2024[1982]). La invención de la soledad. Barcelona: Planeta, p. 108. English version: The Invention of Solitude. New York: Faber and Faber.

[4] “Cartoonists especially tend to be either attic workers or basement workers, and I’ve had this theory for years that those who work in the basement had trouble with their moms and those who work in the attics had trouble with their dads” (Alec Marsh). Braithwaite, J. (ed). (2017). Chris Ware: Conversations. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, p. 200.

[5] Ibid., pp. 195-196.

[6] “Inking is kind of a relief he [Chris Ware] gets. He makes a lot of phone calls; he talks while he’s inking. He’s like a teen-age girl. (…) He has many friends that he’s never met, and he’s known them for years exclusively through the telephone.” Brownstein, C. (June 2001).

[7] “Mr. Brown, the human clown. This is how the kids call him. And if I was gonna draw him, I guess that’s how I’d do it”. Ware, C. (2019). Rusty Brown. New York: Pantheon Books.

[8] “If the conjugal relationship of image and text produces a kind of music, what is it? Not just an erotic reverie but an eroticized way of reading and looking?” Taylor, C. (2022). Image Text Music. London: SPBH Editions.

Leave a comment