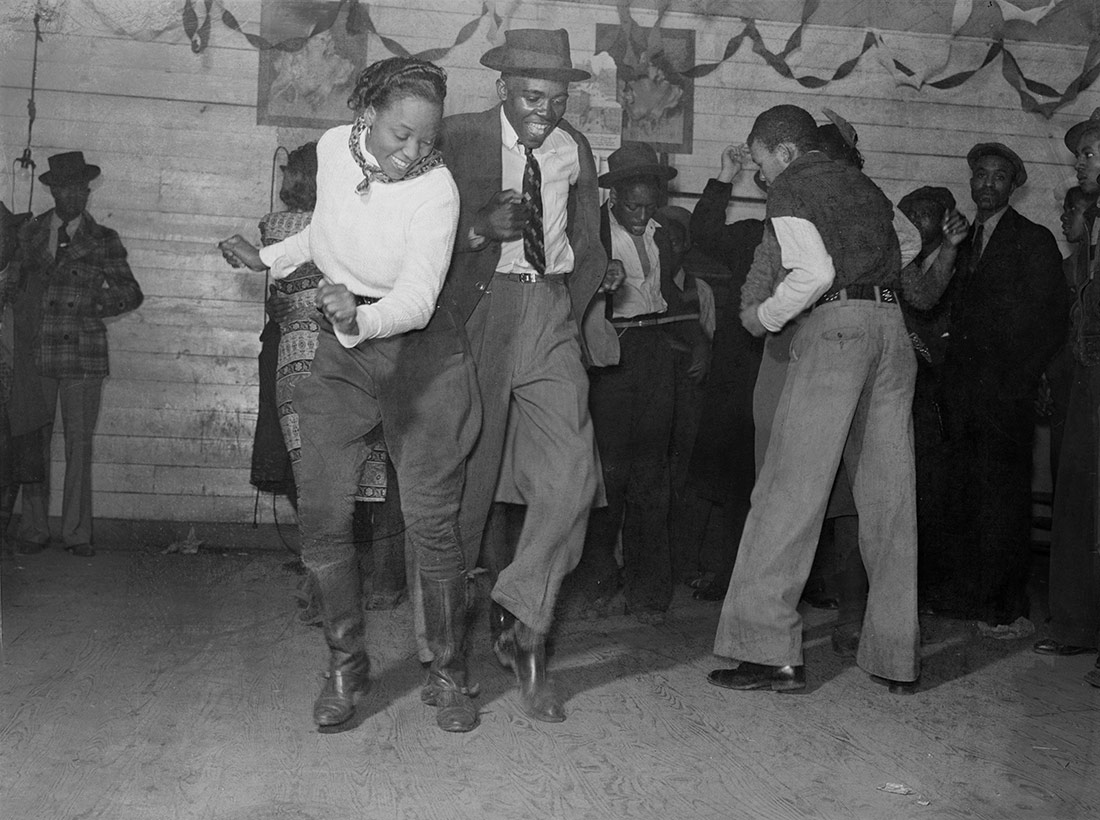

Jitterbugging in Negro juke joint. Mississippi, 1939 | Marion Post Wolcott, Library of Congress | Public domain

Electronic dance music and rave culture are undeniably intertwined with all kinds of liberation movements. But their potential for experimentation with identity and desire is at risk of being co-opted by the market and by fascism.

I had never seen so many Nazis in one place as I did one night at a superclub in my city. Electronic music had recently burst into my life as a force of liberation. Accustomed to spending my free time on more mainstream, commercial pursuits, I had found raves to be a welcoming space – somewhere I could dissolve into strangeness. Over time, though, I began to notice things I didn’t like: the commodification, the bad trips, the guys casually doing Sieg Heils in the middle of the crowd. Initially, I had thought I was getting a firsthand experience of the political potential often talked about by afficionados of electronic dance music. It didn’t take me long to realise that the whole thing was far more complicated.

The story we’ve been told goes like this: the rave movement began as a euphoric explosion of love. After acid house and ecstasy arrived in the UK, the storm of self-organised macro-parties that swept the island in the summer of 1989 began to brew. The result was a never-before-seen dissolution of social divisions into on ongoing festival of communal love. “Thanks to the ecstasy,” explains Simon Reynolds in his book Energy Flash, “all the class and race and sex-preference barriers were getting fluxed up; all sorts of people who might never have exchanged words or glances were being swirled together in a promiscuous chaos.”

In reality, the roots of electronic dance music go directly back to various struggles for liberation. From disco’s associations with sexual and gender fluidity, through the Black and queer scenes of Chicago that gave birth to house music, to the African American producers of Detroit who pioneered techno, electronic dance music was incubated in the safe spaces of minority communities as a force that ramped up experimentation with identity and desire. Even today, any casual observer or participant will see that this relationship with dissidence and the margins of society is still alive.

But it was never that simple. The power of the dancefloor to dissolve and reassemble identities could also be used for other purposes. “Far from the communal dreams of certain factions of rave culture, with the promise of new Dionysian collectives,” writes Benjamin Noys in his article Dance and Die, “the combination of dance music with drugs rendered possible a practical anti-humanism – the disintegration of the ego under the forces and forms of drug and dance induced-states of dissolution.” In other words, rather than a mystical unity, what was unfolding was something close to a sci-fi dystopia – the individual breaking down into the machine.

No philosophical wrapping is needed to see this dark side. It soon became clear in the evolution of raves and large-scale parties in the early nineties. Some clubbing scenes were plagued by a certain death drive, reflected in the ethos of “dance till you drop.” This was the case with the infamous Ruta Destroy (destroy route) in Spain, which the media grabbed upon to stir up a scandal. But the real threat was more concrete – the introduction of the far right into many electronic music scenes, especially in Spain.

Then there is the matter of appropriation and reproduction by the capitalist model. Over the years, through successive speculative bubbles, electronica and party culture have suffered from the market’s abstraction of experience into commodified form. Nowadays, a rave has ceased to be a self-organised party to become just another experience to buy on your event app. None of this erases the singular potential of any particular type of music or event, nor does it reduce participants to mere passive, faceless consumers. But the truth is that all of today’s political and economic forces incentivise this shift, progressively refining the means by which they do so.

A rave is not inherently a door to epiphany or liberation. It is an artifact of complex potential. As Ana Gorostizu explains in her manifest, electronic music is a praxis – something more than a mere activity, but less than a political practice in the strict sense. There are many reasons why it has been closely related to different liberation movements, although these reasons are also limited. Its transformative power – well known and widely preached – can just as easily be inert and useless if it remains closed in on itself. Safe spaces for expression and experimentation with identity and groups are often necessary, but rarely sufficient. The rave is just one of these possible spaces, which is why we should defend it as a practice, but also be wary of its supposed magical potential.

The rave is a liminal space. Like psychedelic drugs, extreme sports or motor racing, the adrenergic appeal lies in experiencing the limits, and in its potential for estrangement. To strip it of this component would be antithetical. To impose rigid parameters of control would be a contradiction – a police-like approach at odds with the spirit of the rave.

But fascism, too, feeds on spaces of rupture and transformation. Its revolution, albeit deliberate, is purely symbolic, which is why it seeks to appropriate the power of aesthetics. No concrete cultural practice, in the abstract, is inherently anti-fascist, nor does it have an innate resistance to being co-opted by reactionary forces, let alone by the market. That is why cultural practice, in general, requires a commitment to anti-fascism in each and every case in which it occurs.

At times, the term “antifascism” is applied far too loosely. Practices that are nothing more than aesthetic have been labelled as anti-fascist, as has the broad and often purely rhetorical defence of liberal institutions. Here, I set out to work with a more concrete definition of antifascism: the practice of preventing the advance and entrenchment of reactionary paramilitary forces. This must not be a merely theoretical exercise – it must be carried out at all times, by all means and in all concrete situations in which the need arises.

One such concrete practice is the rave. We already know from experience that its liberatory and transformative potential is not enough to save it from being captured by reactionary forces. But the usefulness of raves, even the specific need for them, is undeniable. That is why, like any other cultural practice, they must be constantly and consciously defended. The forms that this struggle takes will vary from case to case, and the forces capable of carrying it forward are, unfortunately, scarce. But you must not abandon your rave to the forces of reaction. Defending the liberatory potential of art and rave culture from the grips of fascism is not just an abstract imperative. It is a political mandate – to do everything possible to resist this danger every time it rears its head.

Leave a comment