CC BY Albert Tercero

The video game designer Sid Meier defined games as “a series of interesting decisions”, from which it can be deduced that understanding a game involves, first and foremost, identifying and thinking about the most important dilemmas that it presents to the player. So let’s imagine that contemporary video game culture is a game. What are the “interesting dilemmas” it poses nowadays? In this text, I set out to explore three such dilemmas which, in my opinion, are crucial.

Game/Technology

Games may well be the most paradoxical and contradictory element of digital society: they are both a problem and an antidote in our relationship with new technologies. On the one hand, ‘gamification’, the veneer of entertainment adopted lately by all types of digital technology, from apps to social networks, can favour their consumption and acritical use, making us believe that these and other types of digital technology are really just ‘inoffensive’ entertainment. On the other hand, Miguel Sicart, author of Play Matters (2014), defends certain essential aspects of games, such as creativity, personal expression through play and ‘playful’ exploration of limits as the best manner to relate to the technological world that surrounds us. He proposes this playful-critical attitude towards new technologies as a necessary way to make up for their widespread use for utilitarian and production purposes, and for those video games that point basically and unequivocally to efficiency as the path to success.

It might interest you

Sicart’s theory-come-manifesto stresses ‘play-as-appropriation’, the ideal of a rebellious ‘homo ludens’, play as a carnival-like act: ‘carnivalesque play takes control of the world and gives it to the players for them to explore, challenge or subvert’ (2014: 4). Similarly, in his article ‘At home we play like this’, Víctor Navarro gathers interesting examples of ironic forms of play. For example, a group of players who basically spend their time dancing to Destiny, an online war fantasy game, or Robin Burkinshaw’s ‘project’ of playing as living as a homeless person in The Sims and blogging about his experience. As Navarro says, this is ‘a crossover between the subversive study of some systems devised for Ikea consumerism and TV series narratives (…) The thesis is clear: in our real world we play in easy mode’. A recent example is the case of Claire, a young running enthusiast from New Jersey who always takes routes in the shape of a penis, registering them on a digital map of the city using the app of a sports brand and publishing them on social media. Her routes make a sarcastic point about apps that use a ‘cool’, ‘gamified’ veneer to promote social acceptance of personal data processing and surveillance algorithms.

The work of Sicart and Navarro shows the value of and need for a playful culture of resistance against certain aspects of digital society: of defending the flexibility and emotionality of games against functionality and mechanical logic; creativity and personal expression against hyper-efficiency and technological determinism; and users’ critical awareness in their relationship with new gaming and gamified technologies.

‘At stake is more than our culture of leisure, or the ideal of people’s empowerment; at stake is the idea that technology is not a servant or a master, but a source of expression, a way of being (…). In the age of computing machinery, we need to see play as both playing systems and playing with systems, as appropriation and resistance of systems’ (Sicart, 2014: 33 i 98).

CC BY Albert Tercero

Escapism/Empathy

‘That’s the thing about video games, they can give you experiences that you can’t have in real life, that you haven’t had, so it can be, hopefully, an experience that can add to someone’s conception of how people are in the world’. Karla Zimonja (video game creator, co-founder of the company Fullbright; in: Muriel & Crawford, 2018: 127)

It might interest you

In a media that has historically been criticised for ‘escapism’, in recent years different creators have explored and strengthened the potential of video games for social empathy. As suggested by Muriel and Crawford in their recent book ‘Video games as culture’ (Routledge, 2018), video games, understood as a designed experience, have huge potential for putting us in other people’s shoes, making the gaming experience an experience of someone else’s perspective, helping us to understand it. These don’t have to be ‘educational games’ in the strict or conventional sense. To the contrary, the main ‘empathy games’ around today are closer to the idea of an ‘indie video game’: for example, ‘Gone Home’ (Fullbright, 2013), which narrates the main character’s teenage crisis – the discovery that he is gay and his relationship with his parents; ‘This War of Mine’ (11 bit studios, 2014), which places the player in the shoes of a group of civilians who are the victims of war, showing the harsh reality of their day-to-day lives (instead of the usual ‘soldier’ avatar offering); or ‘Koral’ by Carlos Coronado (2019), a poetic experience of ocean scuba diving that promotes environmental awareness and the conservation of nature.

However, the independent designer Anna Anthropy has warned of a ‘problem’ with empathy games: the risk that they be used as a ‘shortcut’, an easy, quick and pleasant (playful) gesture of empathy for players, which ‘calms’ their conscience without promoting a deep understanding of the problem or true commitment to understanding and helping others in real life (Muriel and Crawford, 2018: 136).

However, the interest in the ‘new wave’ of empathy video games should not lead us to a negative or reductionist understanding of video games based on fantasy and escapism: ‘travelling’ to fantasy or science-fiction worlds has always stimulated the imagination and creativity and invited us to practice the healthy art of breaking away from our cognitive and sensory routines to explore other worlds with a fresh outlook. This does not run contrary to the ability to empathise – quite the opposite. Fantasy or science-fiction video games can also be empathetic, or at least they have the potential to be, even though this may be in a different way to the most well-known empathy games.

Indeed, the contradiction between escapism and empathy in contemporary video games is a false or misleading dilemma, but one that is worth bearing in mind in order to understand the present and future of video games as a means of expression.

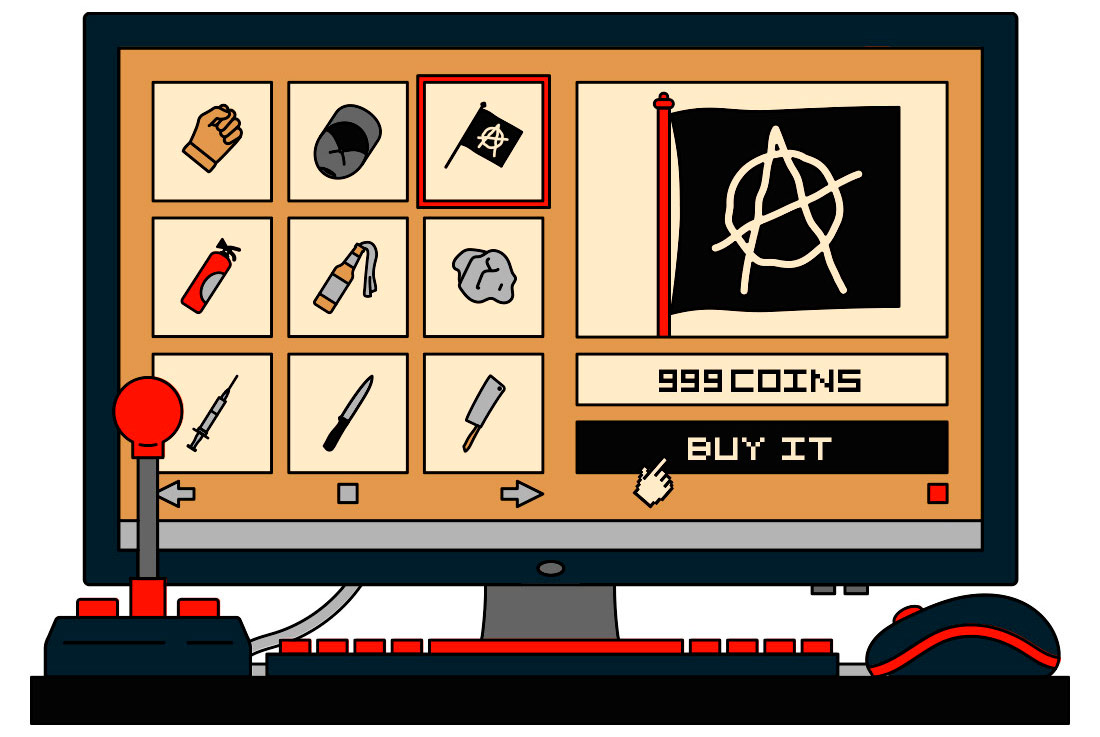

CC BY Albert Tercero

Participative culture/Digital playbour

Ready Player One, the latest Steven Spielberg film based on the novel of the same name by Ernst Cline, deals, albeit latently, with the key elements of the third area of conflict we want to look at in contemporary video game culture: the conflict between participative culture and digital playbour.

The story (to give a brief synopsis) takes place in a dystopian future in which the world is in the thralls of a chronic energy crisis resulting from the abuse of the planet’s resources in preceding decades. It is within this context that a massively multiplayer online role-playing game called OASIS becomes the sole life motivation for many young people. The owner of OASIS, the billionaire James Halliday, announces that he is about to die and that he will create a final challenge for players. The first player to successfully complete Halliday’s ‘Greatest Challenge’ will inherit his fortune and become the new owner of OASIS. For Wade Watts and his friends – the film’s heroes – this challenge gives their lives new meaning. Enter the baddy: a company named Innovative Online Industries that has put together an ‘army’ of gamers to try and take control of OASIS whatever it takes, without the slightest concern for fair play. From this point on, the story turns into a kind of allegorical confrontation between young rebels and a perverse incarnation of digital capitalism (IOI). But are Wade and his friends really ‘young rebels’? The ideological deconstruction of Ready Player One gives food for thought in this regard, although we need to include a brief ‘flashback’.

It might interest you

In the mid-to-late 90s and the noughties, the optimistic narrative of ‘participative culture’ (led, in the academic sphere, by Henry Jenkins) was widely accepted. This discourse celebrated the demographic made up of gamers and fans, considered to be ‘prosumers’ (consumers of popular culture who are also creators or, at least, co-authors of content), aligned with the ideals of collective intelligence and participative democracy. Even though it hasn’t lost all its relevance, this narrative has gradually lost strength in parallel with the growth in ‘platform capitalism’ (Nick Snirceck, 2016) and the debate around ‘digital playbour’ (Kücklich, 2005). As is well known, platform capitalism is underpinned by the action of individuals creating services (for Airbnb or BlaBlaCar) or content (for Facebook or Youtube) which are then monetised by tech companies. Online video games are part of this logic: fans of online games such as World of Warcraft, Minecraft or League of Legends feed inputs into these online platforms in what for many is more than a simple hobby: they help to improve the game experience, create content (sometimes ‘mods’ to the original game), guide new players, report any users displaying inappropriate behaviour, etc. This is what Kücklich termed ‘digital playbour’ in reference to the ambiguous mix of play and work, pleasure (the user’s) and productivity (the company’s). The most recent area to use ‘playbour’ is e-sports – professional video game competitions – currently one of the industry’s most lucrative sectors. It’s an area with both a positive and a dark side: although in the most important competitions the players tend to have contracts, it is also true that the fervour amongst players and their desire to become the next Messi of the video game world means they often end up accepting unclear or unsuitable employment conditions.

Having said all this, the answer to the question we asked above (are Wade and his friends really ‘young rebels’ opposed to the capitalism symbolised by IOI?) should have become more complex… In the story they obviously rebel against IOI, but at the same time they implicitly embody the ideal consumer of digital capitalism: young players with an extraordinary passion and dedication to OASIS, to a large extent disinterested (they were already huge fans of Halliday and OASIS before the Greatest Challenge), obsessively knowledgeable about the history and each nook and cranny of the virtual world, content creators who act as role models and guides for other players… while also projecting a certain romantic vision of young e-sports competitors. Basically, they are not simple consumers, they are ‘prosumers’ and ‘pro-gamers’. But, unlike in the Cline/Spielberg cyberpunk fairy tale, in the real world it isn’t so clear whether this offers any guarantee of social change.

CC BY Albert Tercero

Leave a comment