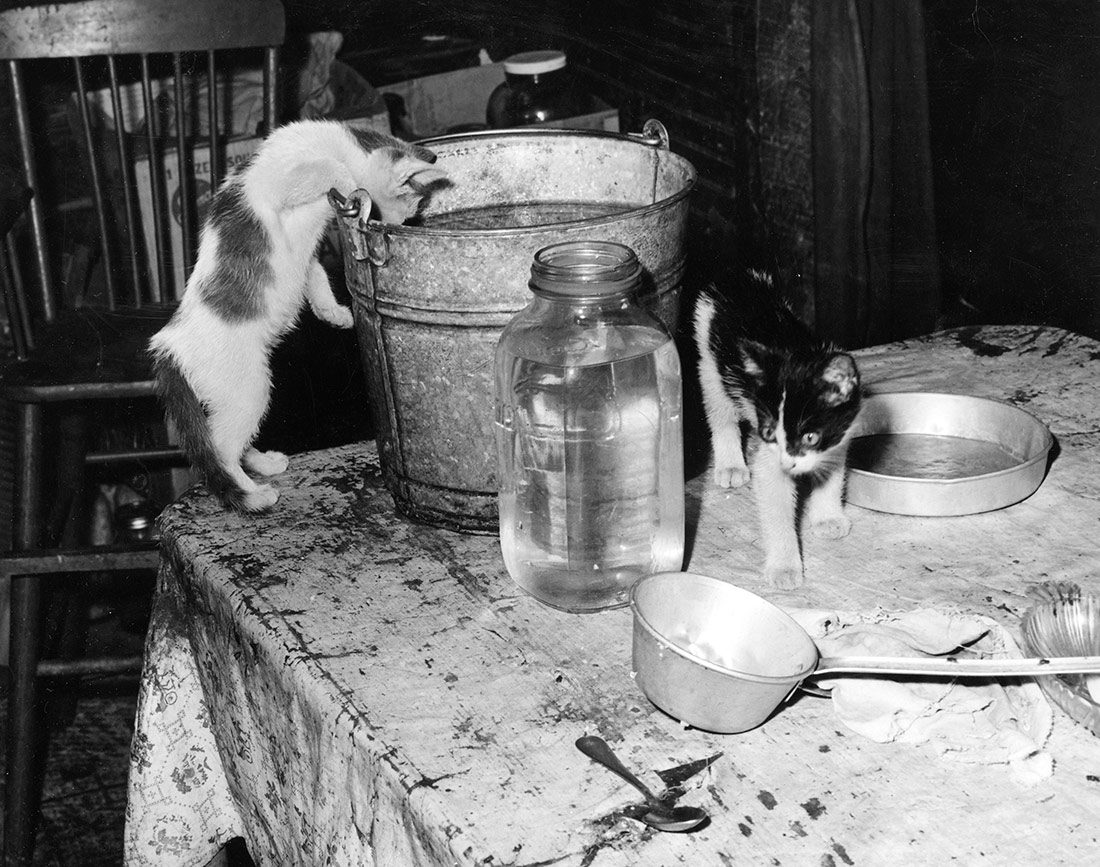

Kitchen in a miner’s home. Kentucky, 1946 | Russell Lee, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration | Public Domain

Thoughts on the creation of Canto jo i la muntanya balla and on the creative process now that the novel has been written and finished. On how the process of writing accommodates both the omniscient author and the inscrutable creative act. Through the metaphor of “cooking novels”, we delve into the art of creating stories. With the kitchen as a place of alchemy, we talk of ferments and yeasts. Of time and sediments. Of forming and shaping.

I’ve come to talk about cooking. About cooking novels. One novel in particular, called Canto jo i la muntanya balla (which may be translated as “I sing and the mountain dances”). About ingredients and quantities and temperatures, ways of cutting, mixing and waiting, about how many tomatoes and how many handfuls of almonds “like this”[1]. But I realise now that I don’t want to talk about delicious dishes created following a list of more or less precise instructions and tips, in the bright kitchens with clean hobs of happy cottages or TV sets, but the type of creation that is difficult to scrutinise, mysterious, self-sufficient and imprecise, of potions, poisons, ferments and cheeses, in unkempt kitchens and damp caves. Because the process of creating them is so unfettered, so ambiguous, so abstract, and yet so scientific and precise, that it is somehow magical. Magical in the way that rennet and milk combine to make cheese[2].

Some time ago I undertook a project called Notes on a novel (that I am not going to write), or the swimming pool, or the hair, the herb and the bread or the tomato plant, which started off by recounting a true story and a recipe that a young Icelandic man once told me.

The man was called Bjarki, and a few years previously he had been in love with a young woman, who we will call G, and had made some bread for her, so that she might also fall in love with him. To make bread, he had stolen a hair from G’s head and picked a mountain herb whose name he didn’t want to disclose so that I couldn’t follow his recipe. Bjarki then cooked the bread with the herb and the hair in it, and gave it to G, who ate it and fell in love with him. And they would have lived happily ever after had he never told her anything about the trick with the bread. When she found out, she got angry and left and Bjarki never saw her again. In the explanation to the project I added my own note: “Like in the Pyrenees, when you tell a water-woman that she’s a water nymph and she marches off and you never see her again”. At that time, I was already researching into water nymphs before writing what would become Canto jo i la muntanya balla.

An Icelandic kitchen. Silfrastaðir, ca. 1900 | Cornell University Library | Public Domain

The project Notes on a novel… was a non-novel project. A project on seeds that don’t grow or on planting an apple tree and seeing a tomato plant sprout up. In a public Google Drive document I was preparing to write a novel (which I did not intended to write), and I was working with a collection of snippets of text, dialogues, rough sketches of characters, notes, reminders, lists of ideas, transcriptions of conversations, anecdotes, stories and legends that would hopefully allow me to reflect on the interests, stimuli, research, thefts and experiments that go into the process of constructing a novel.

But I won’t go on anymore about a project that is already done and dusted. (Or leave poor Bjarki wondering why, six years later, I’m still ruminating over a story he told me one fine blustery day). Let me just say that what I’m trying to do here today is the opposite of what I did that time. Notes on a novel…studied the before, the present, the process of the creative act. This article looks at Canto jo i la muntanya balla from the other side. Now that the novel has been written and completed. Searching for the doorway into a dark and dirty kitchen, one that is also now empty, into a cave, a hut, an unkempt and cluttered tumbledown house, abandoned and covered in brambles.

To find the way back into this damp cave where we can potter around with the stimuli, the trial and error, the crumbs, tools and leftovers of Canto jo…, as I left no trail of breadcrumbs or white pebbles, I’ve started by opening the document where I wrote up my first research notes. Date: 8 April 2017. The first topic that appears, in capital letters, is THE GOGES (the water nymphs). The second topic of research is WITCHES. And not without some joy, I think that these two interests, these two stimuli, are the embryos, the seeds, the heavy and rusted key, the good fungi of the project. The door. Bingo! The way in is fresh. The research document continues with such subjects as hunting accidents, how animals react before and after a storm and rains of animals.

Very unpleasant weather or The old saying verified: Raining cats, dogs and pitchforks. 1820 | George Cruikshank, National Gallery of Victoria | Public Domain

I walk into the kitchen and look at the black hobs, the soot-covered walls, the cold fireplace, the worktops covered in moss and spiders, and I think how Canto jo i la muntanya balla was created “like this”: I threw a series of interests down onto a dark table (water nymphs, witches, rains of animals, etc.). I researched them, they led me to further enticing discoveries and I gradually began to get a clear glimpse of the stories I wanted to tell and how I wanted to tell them, and I got down to work.

Now that we’re pouring over entrails to decipher how things were rather than how they will be, I also open the document where I wrote the first lines of text. Date: 22 March 2017. Prior to the research document. I’m getting somewhere! It starts off with a list of five words, that read:

“hunter

witch

ghost

animal

itch”

I’d laugh if it weren’t for the fact that I recognise myself in the words. It continues with notes such as: “A lot of people living together in the forest: the water nymphs + Hilari + the witches + the mother, Sió, like a child + the father with his head split open by lightning + republican dead”

And: “the morning Hilari died, the forest and the mountain were sad; not because Hilari had died, but because some mornings simply are sad.”

A Witches’ Kitchen. 1610 | Frans II Francken, Kunsthistorisches Museum | Public Domain

But there is more you need to know before we start talking about recipes for potions. From the very start, I imagined the area, the landscape (this small corner of the world between Camprodon and Prats de Molló, where the novel is set), like a geological stratum. An area covered in layers. Layers of history, tales, legends, footprints of those who had passed through the place or lived there. And I could clearly see that I was interested in all those layers, all those footprints, those left by men and women, but also by animals, clouds, mushrooms, ghosts and water nymphs. There are also some more things I should explain to give a clear picture. For example, a handful (or “almosta”) of inspiring works that I’d already read or was reading during the process: Tony Morrison, La mort i la primavera, Drames rurals, Mariana Enriquez, Verdaguer, my friend Lluís-Lluís, Eggers, Pep Coll’s Muntanyes maleïdes, Lucrecia Martel, Camille Henrot, Mark Dion…

I look at the solitary chair in this kitchen with its broken tiles and weeping wall and I remember how I shut myself away here, in this cave that was mine and that smelled of smoke, and how I worked in here for months, and how I came out only now and then, and sometimes it was noon, and sometimes the moon was waxing and at other times I could hear the roe deer bleating and at others (mostly), I heard the sound of sirens from London police cars, because most of the text, let’s face it, was written at 45 Gunton Road, London.

And I don’t want to make out, or I shouldn’t make out, that I didn’t have a tyrannical, masterful, absolute, cruel and unperturbed authorial control over everything I wrote. But neither can I deny that during the process, or the creative act, things occur that are intangible and difficult to scrutinise and that have to do with ferments and yeasts. With a time and a sediment that you didn’t know you were accumulating. With good fungi from my caves and the caves of other folk. With the enzymes of blindness and potions that you try on instinct. With playfulness and with failure. With the drugs of fun times. With the enjoyment of a certain solitude and the pleasure of occasionally being told stories, getting to tell them or taking someone by the hand.

And now, to finish off, I’d like to transcribe some imprecise recipes from the unkempt hut that may be most useful:

Cow’s milk and rennet, in a dark cave with good fungi, make cheese.

Honey, yeast and water, on the chest of drawers at 45 Gunton Road, make mead.

Flour, water, yeast, an unnamed herb and the hair of a water-woman, make bread for falling in love.

A toad beaten hard with a stick until it puffs up and dies, laserpitium gallicum and arsenic make an ointment to be placed under the armpits to summon up the “the Great He-goat” (aka the devil).

And finally, toads, snakes, frogs, liver and baby lung make a poison that’s right deadly[3].

[1] This winter I asked my mother how to make romesco sauce for the calçots. My mother answered: “It’s very easy – a large head of garlic and three roasted tomatoes, four ñora peppers and a handful of almonds, ‘like this’”. She said “like this” and cupped her hands together to form what in Catalan is called an almosta. “Almosta” is a fantastic word. “Almosta: What a person can hold in their cupped hands”.

[2] I mention milk and cheese as a nod to the research for the novel I’m working on now.

[3] The last two recipes are taken from the real confessions of people accused of witchcraft in Catalonia, which can be found in “La persecució senyorial de la bruixeria al Pallars: un procés contra bruixes i bruixots a la Vall Fosca” (1548) (“The noble persecution of witchcraft in Pallars: a process against witches and warlocks in Vall Fosca” (1548)) and in Orígens i evolució de la cacera de bruixes a Catalunya (segles XV-XVI) (Origins and evolution of the witch-hunts in Catalonia (15th-16th centuries)) by Pau Castell Granados.

Leave a comment