Fly, Caterpillar, Pear and Centipede (fragment) Inside: Mira calligraphiae monumenta (1561-1596). Source: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Getty Open Content Program.

In the face of the social divide triggered by the current crisis, the concept of community has been gaining strength. Even though the term has been misused and distorted, and is all too often used in the consumer market, in the last few years we have seen the emergence of many different attempts to create communal spaces as new autonomous models that offer an alternative to the existing institutional framework. These experiences are the best possible illustration of the potential of community.

The term “community” has become a catch-all concept or strategy in recent years; a category open to the verbal manipulation that allows us to appeal to and challenge different and often antagonistic social devices.

The current crisis and its management are favouring the radical implementation of the neoliberal project, through the gradual dismantling of the welfare state (which is still under construction in most countries southern European countries). The decline of this model leads to a worsening of the social divide, making it necessary to come up with new frameworks in which we can recognise ourselves alongside others in search for an encouraging “us”.

Community, as a space from which to transform the foundations of our everyday reality, becomes a pre-existing lifeline that we can now turn to. But in order to return politically to a community that has always been there, we must also readjust the language that goes with it, starting with the word “community” itself.

The target and the “objective” community

The triumphal discourses around Web 2.0, online marketing and advertising never tire of talking about objectives. Their objective is to reach their target – target market, target audience, target group –, the ideal recipient of each specific campaign, product or service. At the same time, recent market research studies are trying to identify new communities that are basically made up of individualised elements. Communities in which “one and the other act, but none of one acts in the other”[1]. This concept, which was spread principally by the cultural and entertainment industry, has also found its way into public and private institutions, which analyse the logic of “communities” in an attempt to come up with special marketing plans that will increase the share of their product or content.

These are “objective” communities in as far as the links that bind them arise from an interest in third elements (films, comics, TV programmes, clothing labels, music groups, etc), and not from the development of the community by its own means and for its own sake, in accordance with its own interests and growth.

Subjective communities as an alternative form of institution

In contrast to these objective communities designed by the market, many new and old communities are engaged in designing models that oppose power. Communities that spread as a different, disruptive form of institution, and that emerge from the capacity for collective assemblage of the individuals that form them.

We are talking about communities that are forged through the recognition of shared weaknesses and strengths, through the desire to generate small spaces of autonomy with the ability to grow and multiply, based on the intersubjectivity and interdependency that are inherent to us.

Below we look at a few spaces of communal assemblage that offer a new type of institutional framework in the political, economic and cultural fields. A brief overview of the strength of communities that generate alternative value systems based on collective needs, in the face of the external market that surrounds them.

New community spaces

The impact of the crisis and current governments’ lack of political will to curb its effects is leading to progressive social fragmentation. The hardship involved in securing the basic means for a decent life is seriously harming many segments of society. To combat unemployment, public service cutbacks, and the government’s failure to take action relative to mortgage foreclosures, new spaces of production have emerged and started to autonomously generate all types of resources.

El Patio Maravillas. Source: Galex.

Known as Self-Managed Social Centres or Community Social Centres, these new spaces produce a new kind of institutional framework based on counter-hegemonic community production. In Spain, spaces that already have a long history, such as La Invisible in Málaga, El Patio Maravillas in Madrid, and Ateneu Candela in Terrassa, as well as new projects such as the Luis Buñuel Community Social Centre in Zaragoza, are being used by citizens to promote critical thought and social self-organisation. They are a new form of community management that demands a transfer of sovereignty from the public realm to the commons, based on the power of the community to manage matters of common interest such as buildings, infrastructures, educational projects, and so on. These spaces require a new social agent that is outside of the government umbrella; an institution of the commons for communal interests that focus on reproducing a decent life for and from the community.

The value of community

Subjective communities (made up of a shared intersubjectivity) spread in as far as they are able to manage one or more common resources in the face of a hegemonic power that generates scarcity. This communal management of tangible or intangible resources does not rule out earning and income, but the logic of a new institutional model means that these economic projects are far removed from the monopolistic extraction and the profit maximisation of corporations.

The new community economy, focused around a common resource, is able to create sustainable models while also generating returns for its community. As Marga Padilla explains in this article, the idea is to “see how the existence of global commons that are compatible with economic activity (read free software) are a very good means by which to redistribute knowledge and income, because they allow people to set up projects at a very local scale – in this case the neighbourhood – using the global knowledge generated through cooperation, and at the same time nourish and add value (in this case a critical mass of active users).”

Projects such as Softwarealpeso, a store that offers comprehensive free software support at the San Fernando market in Lavapiés, Madrid, illustrate a community economy model based on designing for the community rather than the market, on a commitment to reuse and recycling, the use of standard parts that facilitate replacement, and on opening up the code that allows you to learn to do it yourself.

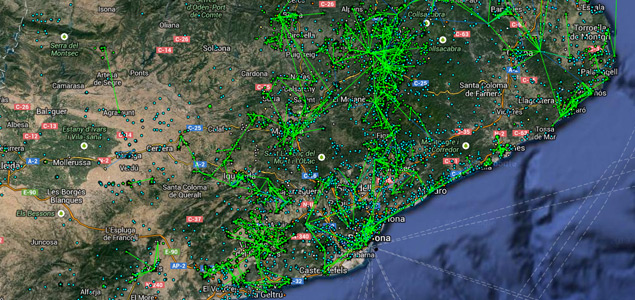

Guifi.net is a paradigmatic community management project that revolves around an important resource: telecommunications networks. The Guifi.net initiative began to develop in 2005 in the region of Osona (Catalonia) as a result of the unwillingness of telecommunications companies to provide connections to small population centres due to the poor economic returns that they entailed.

Finding themselves ignored by the government and telcos, the inhabitants of towns such as Gurb, Calldetenes, Santa Eugenia de Berga and Vic began to build an open, user-managed network that has ended up becoming the most important free, open and neutral telecommunications network in the world. Mostly wireless, guifi.net has over 31,701 nodes, of which more than 20,332 are currently operational.

Parallel culture

“Culture is ordinary, in every society and in every mind” (Raymond Williams). Communities also become subjective by recognising themselves in their ordinary, common cultures, which they identify with and reproduce. This process of self-recognition was slowed down in the course of the 20th century by the audacity of the cultural industries that managed to appropriate, incorporate and domesticate part of that communal cultural production. But the awareness of that ordinary basis of cultural production can sometimes end up generating other, more community-based management models that lie outside industry channels.

If we could name one area in which this self-recognition has been gaining strength in recent years, it would be the field of popular music on the periphery. The resignification of their musical heritage has allowed these communities to develop new music management models that are not those of the music industry and public programmes, and to reappropriate a common, autonomous, symbolic space.

Music initiatives such as La Champeta (Colombia), Tecnobrega (Brazil) and Manele (Romania) have developed innovative social models based on music communities that recognise themselves in an ordinary cultural legacy. Their musical heritage addresses their living conditions, their language, their imaginary and their relationships, which are nothing like the traditional artist-fan model. These projects are about context-based music, made through and for a community.

While Tecnobrega and La Champeta have used the exploded CD-R on MP3 – along with live shows – as their basic medium of dissemination on the informal markets in outlying areas of cities in Brazil and Columbia, the Rumanian project Manele was broadcast through a multitude of community pirate radios (created by the Roma people to share their culture) on the outskirts of Bucharest. The music no longer flowed through the usual channels, and the community found its own way to reproduce and spread its culture without industry censorship or government regulatory restrictions.

Community links

The communal aspect of autonomous spaces, economic projects and cultural contexts irredimebly arises from the links that make us a society, that are part of our reality whether we are aware of them or not. A community becomes subjective and political in as far as its “selves” recognise each other as equals, and decide to grow autonomously through common intersubjectivity, against an antagonistic power that hinders their survival. Fraternity and commitment thus become the foundation for a “collective, tentative power of action that reappropriates our capacities and our possibilities of life.”[2]

[1] p. 123 / Un mundo en común, Marina Garcés.

[2] p. 117 / Un mundo en común, Marina Garcés.

Leave a comment