Kid on a swing. Caldwell, Idaho, 1941 | Russell Lee, Library of Congress | Public Domain

In 2012, the technology journalist Paul Miller went offline for a year. Back then, some of us thought it seemed a little over-the-top: it was the year of the 2.0 boom and growing enthusiasm over collective intelligence. Almost a decade later, we’ve all seen the good and the bad side of the web, while criticism about the darker side of cognitive capitalism and the attention economy is growing. So it is that, inspired by the possibility (or impossibility) of disconnection, we’ve asked eight collaborators to give their opinion on the subject. These texts have been fed into a neural network which has also generated its own answer.

- Living Dead, by Anna Pacheco

- To Be Connected or Disconnect, by Efraín Foglia

- Very Brief Guide to a Healthy Digital Diet, by Felipe G. Gil

- Bird, God, Cloud , by Irene Solà

- Reconnecting, by Jorge Carrión

- B-I, by Libby Heaney

- Des…, by Liliana Arroyo

- The False Weight, by Maria Cabrera Callís

- El Mal Alumne, by Estampa

![]()

Living Dead

Anna Pacheco

What happens when someone who has died leaves a WhatsApp group? What mechanism is activated? What type of sadness (a new type, certainly) is caused by the idea of someone who is no longer here actively leaving a place that only exists on the virtual level? Logically, we might think that a dead person would leave a group when, in the real world, they disconnect his telephone number. And this might take months, until the living get over the shock and the fear of absence of their loved one. In my case they took four months and, when it happened, the impact was huge. We found out when we received that standard text that appears to tell you that so and so has left the group. Most of us didn’t know how to respond or react, neither with worlds nor symbols. Only one person plucked up the courage to respond, by means of an emoji with a tear + a broken heart. It was an understandable thing to do, but the result seemed rather crass. No one else said anything or managed to ameliorate the situation. The moment was pushed out of my head twenty minutes later by some unimportant matter or other. Someone said “I can’t find the keys for my scooter” or something similar. Then someone shared a link to a news piece and an image of a plate of food. This made me feel a new pain. Another more or less natural impulse is to visit all those virtual spaces where the dead person is still alive, in their own way. 450 photos on Instagram, 150 tweets, the conversation on Facebook where the person told you things. I go back to these virtual and now funeral spaces every time I think about the dead person, which is more or less every day. I go back with a renewed faith and the deep sadness of always finding something new, something I’d overlooked, something I didn’t know; I feel the need to gather all the information of someone who no longer creates any. Their public data are valuable because, for me, they offer an immediate connection with someone who is alive.

![]()

To Be Connected or Disconnect

Efraín Foglia

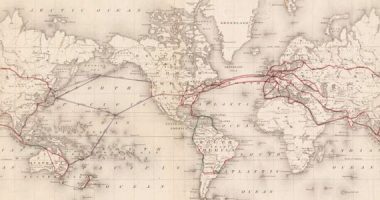

Capitalism is perfecting itself because each connection to the Web produces assets. Each click generates value. The Internet becomes a techno-biological organism that extracts life. The Web shows us its darkness and perversion. Hate multiplies on social media, where racist and supremacist attacks grow. It’s all reason to disconnect. Disconnection from the Internet should be a basic right.

We mustn’t forget that the Web doesn’t belong to them, to those vile netizens. Disconnecting from fear is like losing a city street that you don’t walk down anymore because it’s got too dangerous. It’s a lost corner of the city that no one fought for. There are people who have fought to stop up being excluded from the Web and to make it a more just place. Now, unjust power has disconnected them from life. We have to decide: should we stay connected and resist, or disconnect? “What I love and believe in the most is connection, human connection and the technologies by which that is achieved.” Edward Snowden (2019). #PermanentRecord #FreeAssange

![]()

Very Brief Guide to a Healthy Digital Diet

Felipe G. Gil

There’s a lot of talk about the toxicity of social media and Internet in relation to how we use technology. There are two extremely mundane metaphors that help me to maintain a healthy relationship with the Internet. The first is the metaphor of the knife.

A knife is an essential tool in the kitchen. You need it to cut up food, to make it suitable for eating. But you can get cut by a knife. It can even be used to kill someone. That’s why I think it’s important to differentiate the use we make of a tool from the tool in and of itself. The tool is here, and it’s here to stay. What we need to debate is the use we should make of it. And in this regard, all those uses that serve not to harm others but to make our lives easier, to defend universal values such as equality, diversity, etc. – these are the ones we should be working towards. Internet is a knife that we need to use to cut away racism, sexism, xenophobia, etc.

The other analogy that closely suits my purpose is that of watering. We often think about our relationship with social networks in absolute terms: you’re either connected or you’re not. No one gives a plant more water than it needs each day because this could harm it. The same thing occurs with the Internet and the use we make of technology: a constant drip can be healthier than a complete drought or too much water. We still need to encourage time off and controlled use. But I think we need to find a balance between being hyper connected and allowing our identity to depend completely on social networks and the Internet (too much water) or completely disconnecting and generating what might be an unnatural state of indifference (complete drought).

![]()

Bird, God, Cloud

Irene Solà

One could fiercely defend the problems that come with the possibilities of being practically everywhere, of knowing almost everything, of responding instantly, and also superficially, to any query, of satisfying everyone’s curiosity, of making connections with an infinite number of points. We could talk about the disastrous consequences this might have for our ability to concentrate, our capacity for in-depth understanding, for critical thought, even for empathy. But I haven’t started on this subject with the intention of entering that bramble patch, but to mention that, like someone who picks blackberries without hardly a scratch, on the personal and, above all, creative levels, this all-knowing, all-powerful, undiscriminating, all-linking and unlinking, omnipresent, addictive and besieging tool that is the Internet, with its deeply dark side, is key. Key for some creatives. Not all of us, of course. Important for me, for example. Because nothing I write would be as it is if I weren’t writing it today, in this century, with a computer in front of me which, like an oracle, like a crystal ball, like a reflection in a pool, shows me everything I want to see and quenches my initial thirst with an answer, an image, a sound, a video, the momentary ability to be a bird, god, cloud, to – for a moment – seem understand, know what I don’t know, what I haven’t learnt, what I’ve forgotten, what I haven’t yet seen or experienced. And I realise that if I didn’t use digital methods, it would take me days, weeks to gather together all the information I want to know now, while I’m writing, to go to and from the library or bookshop, to meet certain people, to ask questions out loud, to see with my own eyes how cheese is made or how babies are born (even though, in any case, it would be good if I could do and see and ask all these things eventually). But that without any doubt, I write the way I do due to the possibility of accessing the boundless, instantaneous and jumbled information offered by the Internet.

![]()

Reconnecting

Jorge Carrión

You can leave your telephone on a piece of furniture or charging at home; the watch, wristband and smart clothing are less external, they wrap themselves around you, even most intimately. Meanwhile, the Internet of Things shapes itself into an immersive atmosphere, all enveloping, and the wearable version is designed to be like a second skin. The system of connection pushes out its bubbles: it’s a veritable siege.

Only naked, flying or asleep can we completely disconnect. In the shower, the pool, the sea, on a plane or in bed. Although in time, these spaces will also be assimilated, monitored, converted into data. Because that’s the point: to measure and scan each and every human activity.

To fight, even if only symbolically, against this overwhelming expansion of geolocalised biocontrol, I suppose we will soon start to see the appearance of disconnection protocols, for political reasons and also for wellbeing, for our mental health. At least for a time, while it’s still possible. Because I think the future is quite obviously hybrid: when the sensors are inside our bodies, there will no longer be any way to stop emitting data twenty-four hours a day in any setting, whether urban or natural. Or maybe there will. The history of the future is a series of confirmations that our predictions were wrong.

I realise that between 2007 and 2012 I wrote mainly about the screen (in novels like Los muertos and non-fiction such as Teleshakespeare) and that, conversely, since 2012 I’ve been writing about paper (Librerías; Barcelona. Libro de los pasajes; Contra Amazon). I don’t think it’s any coincidence that this most recent phase has coincided with my becoming a father. Because that’s what it’s about: disconnecting so we can reconnect. With bodies, with the physical world, with newborn skin.

![]()

B-I

Libby Heaney

(All the lines below are things people said to britbot, my online chatbot exploring Britishness, and feature in my B-X book. I chose them because I feel like they resonate with the themes above. The spelling/punctuation/grammar is other people’s)

Because it is less part of society. Bizarre Blokes arguing about women’s bodies, as always. Bonding. By focusing less on naked tits and more on issues like climate change Can I restart?

Colonialism it’s f***** up the entire planet Crappie! Criminal law each to their own yeah Cyber and self harm Decaying place Developing new technologies to benefit our economy. Disconnected. Do you like my algorithms? Do you experience your self? Elementary Equal pay, and equal air time Everyone started getting more knowledge and opportunities. Exactly bro Exhausting Fantastic! Fat LOADS of fat Female For me it doesn’t work. From the start from the very inception of it’s being Generally, ugly Good as new disagreements in general life but it’s not very realistic Good news stories, real life occurences and crowd funding! Good! Got bigger, richer, more equal in some ways. Hard fuckers Hate her! Have no tv He has some foreign language programs shown on Netflix I don’t watch TV anymore. He’s a twit. He was an unrelenting bully. I am bored. I didn’t accuse. I love frsh air and my farts. I suspect you are not listening to me 😉 I think there’s an amazing variety

![]()

Des…

Liliana Arroyo

connect. Turn out the light, turn down the music, climb out of the display case, hide from the noise. Distance yourself to fit together. Don’t look for me, I can’t find myself. Eyes shut to the bombardment. Beep, beep, bop. 1456 notifications and rising. Follow, stop following. Like it, love it. Clap clap. That makes me angry. And I keep going down, further down. It’s never-ending, I think. I keep scrolling, half-heartedly. It goes on forever, I think. Half an hour, an hour, an afternoon… Enough. I’m going to stop looking.

Screen off, dark night. I need to post something. Come on, think. Something people will love. I’ve got it: selfie #52 from the informal session. With filters. Natural ones of course. And this trending hashtag for my original post. Same as the other two million. Shared uniqueness, collection of genuineness. I post, therefore I am. OK, posted. Is that it? Yes. The spiral starts.

I go out, I count to 10. Give it some time… reactions, come on! Seconds in the void. I fill it with fear. Fear of silence. Fear of being invisible. The anxiety of the wait pounds through my head. BA DUM. BA DUM. BA DUM. I breathe, I go in. I want ‘likes’… let’s go. I go in. Notifications, yes! Dopamine rush. I’ve got 10, 30, 50, 200. A flood of ‘likes’. But… Oh no, wait! Where’s my crush?

![]()

The False Weight

Maria Cabrera Callís

The false weight

which increases your sales

shines, above the scales,

like a gold tooth

in a sick mouth.

The false weight that fed the fraudulent sales, that swindled customers who went home poorer, dirtier and diminished by the fear and injustice of knowing nothing about numbers or words, the false weight that shined silently and arrogantly, sitting atop the scales, is today something we create ourselves, through our self-sacrificing work to create the smile sown onto our face and the straw mattress we lie down on, satisfied after the working day, exhausted, docile and actively ignorant, to be warmed up by that iron belly.

Everything that is not here

or that one day was lost

puffs up and grows

like a dead fish

floating on the water

until it becomes

the only possible truth.

The falsa data that grows inside us, tenacious and subcutaneous, blind and stubborn like a mole, digs down until it becomes the only working vein, the only tissue, the only language. The sky must be full of stars, it’s true, but it hangs lower than ever, with a plump belly, close to the ground, in reach of any net. The truth is a bitcoin that no longer jingles in our pocket.

![]()

El Mal Alumne

Estampa

We need to disconnect from social media and disconnect ourselves from the air-conditioned day. Data are published in an immersive, instant and profiling atmosphere. Each click breaks away from the connection. Clicks overwhelm each other and adults start to dissolve into the electricity. But they can take months, they can resist.

Internet, like a dark mirror, has our capacity for concentration and proximity. The web is a datacentre, a place of data, a place or a slide, where personal and collective relationships are created in no time and the system is placed under the table. Internet is a montage of one’s own self: an infinite number of kilometres and more metres of me. And I haven’t completely downloaded.

Silence is a key matter and it’s not very realistic. Silence is an instant and after awareness. A type of silence. A silence that goes from four to two hundred people. A silence, silence. But silence.

A day without internet is anonymity. It has to be done to disconnect. The ceremony begins.

Leave a comment