The Gallery of Lost Art, Tate Gallery.

In May this year, the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona hosted the 2012 MuseumNext Conference, an industry event on the future of museums, new forms of participation and exhibition, and the latest technological innovations being developed in the museum field. On 3 October, a similar event was held in London under the title “Musem Ideas”, where experts discussed the culture of participation.

The conference featured seven presentations by a series of experts from the field of museums in the English-speaking world. Each speaker talked about their recent projects and their current vision of the future of museums. This text summarises some of their ideas.

“What role does the museum play in our society?” Sharon Ament, Director of the Museum of London, explored this question in her presentation Museums in the Era of Participation. Ament believes that museums must be socially committed if they are to recover their importance and centrality. The way to achieve this is by never forgetting the museum’s target audience, the people it wants to engage with. The threat: the autistic tendency of institutions. Ament illustrated her ideas with four examples:

- Bibliotheca Alexandrina, Alexandria, Egypt. During the riots in the Arab Spring protests, volunteers and local residents gathered at the entrance to the library in order to protect its contents. They also wrote thousands of tweets in its defense. The Library is now trying to save the almost 2.5 million tweets that were exchanged during those months.

- Citizens Olympics, another project that collects tweets exchanged by citizens. In this case, the challenge is how “exhibit” and publicise them.

- The Peace Labyrinth, Jerusalem. A site for dialogue between Israelis and Palestinians.

- San Francisco Public Library, USA. As well as a library, the SFPL is also a social centre for disadvantaged persons. A space for active participation

Robert Stein, Deputy Director of the Dallas Museum of Art, and Seb Chan, Director of Digital & Emerging Media at the Smithsonian, Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York, focused their presentation (Bootstrapping Innovation in Museums) around the question: “Is innovation synonymous with more technology?” In their opinion, innovation is synonymous with social change and new cultural aspirations, while technology does not necessarily entail change. They illustrated this with the example of the institutions they work at: the first thing they tried to do is to make information about the collection available to everybody, to all audiences. From the outset, they saw exhibitions as a testing ground for new technologies, and they have tried out a series of different ideas. They believe that “innovation must come from the staff themselves, from the bottom up.” It is difficult to bring about real change and innovation in a museum simply through a directive passed down by management. Furthermore, you can’t have an Innovation Department that operates independently of the overall structure, which is why the Dallas Museum of Art encourages its staff to suggest actions and organises regular meetings to swap ideas and experiences.

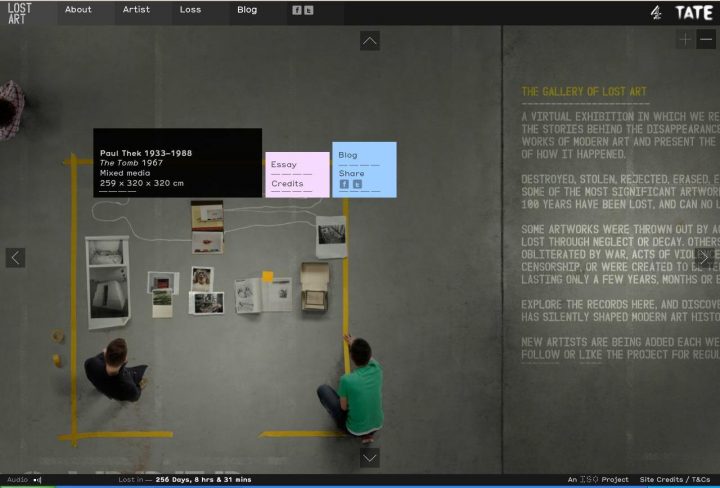

The third presentation was by Jane Burton, Creative Director and Head of Content at Tate Media department at Tate Gallery in London, who talked about some of the initiatives implemented by her department. For example, the Tate Shots project, which produces material for television, the underground, Youtube, etc. It is not educational content, but material that generates awareness, expectations and interest in the Museum’s programme. Much of it is also made available on iTunes, and it has a huge following. Another example is the ‘documentaries’ about artists, the processes of creation behind their works, and other relevant subjects. These are stored in an archive that can be consulted free of charge, such as, for example, Gaza. Norfolk & John Burke. Another Tate project is This is Britain, which invites public figures (artists, comedians, musicians), to see the collection, choose an artwork, and talk about it. For example, a musician plays music in front of his favourite painting; a comedian describes an 18th century painting in an ironic, modern style, etc. Burton also talked about the artistic performances at the BMW Tate Live project; the animated film project for children (Tate movie project) and The Gallery of Lost Art, targeted at a specialist audience of artists and historians who talk about the exhibitions on-site. Although all of these projects have proved to be popular with audiences, the museum faces two challenges: how can we talk about culture to very diverse audiences? (Western debates and expectations are always at the core – but what about Asian or Indian audiences?); and, Is it possible to keep offering free online material and content, given that the museum’s programmes are increasingly dependent on sponsors?

The discussions at the Victoria & Albert, where Louise Shannon is Director of Contemporary Programmes, revolve around strategies to attract audiences to the events programmed at the museum. Since 1999, the V & A runs its Contemporary Programme, which aims to engage young audiences, offer an overall vision (given that the V & A is structured into several departments), and attract new audiences. Shannon discussed four projects: Volume (2004), which activated underused spaces such as the courtyard and the garden; Decode (2009), an online ideas competition around the theme of the exhibition, which was very effective in selling the V&A brand; a series of workshops on robotics linked to The Power of Making (2011), an exhibition that explored this subject and became one of the museum’s most popular projects; and the monthly Friday Late meetings which offer university and post-graduate students the opportunity to participate in V & A projects and join discussions with the museum staff.

Francesca Rosenberg, Director of Community and Access Programs at MoMa, talked about how to engage older audiences, taking into account the fact that aging population in Western countries. She suggested that museums should also target senior citizens (over-65s) who tend to have time, money (they may be potential sponsors), experience and interest. Rosenberg believes that it is also necessary to re-think the concept of ‘family’: it’s time to go beyond just programming for parents and children, and also think about grandparents and grandkids. She gave the example of the Meet Me programme, which addresses Alzheimer’s and people who visit exhibitions on their own, who may be interested in workshops and activities as a way of socialising.

Meanwhile, in his presentation, Adam Rozan, Audience Development Manager at the Oakland Museum of California, compared the future of museums with that of large private companies. “Why does Starbucks attract more customers than small cafes? Why does Barnes thrive while bookshops close down? Why is EdX. The new online education gaining supporters while some Universities are having trouble attracting students? Rozan believes that Museums should be seen as spaces for living, centres for creation and education. But above all, they should be places that offer total experiences, which is why the exhibition areas must be accompanied by cafes, bookshops, and spaces for a range of activities.

Lastly, Lisa Junkin Education Coordinator at Jane Addams Hull-House Museum in Chicago, gave an interesting final presentation, where she talked about “living dangerously” and taking risks: museums must engage their local neighbourhoods, venture outside of the institution and colonise other spaces, so that audiences can become aware that museums are actively related to today’s problems and to their own reality.

View comments0