In “Of Caves and Sybils” Jordi Costa explored the exhibition Kentridge. That Which Is Not Drawn to propose five itineraries. Here, we propose four writers to emerge and table readings and relationships that are not fully explained in it. By means of these insights we reflect on the techniques used by the artist in relation to the current context of digital production, touching on colonial memory and white male privilege, to address contemporary South African film.

- Between the paper and the wall, by Neus Miró

- Art and colonial memory (or forgetting), by Aída Esther Bueno Sarduy

- Being a narrator is not enough, by Lucía Piedra Galarraga

- Filmed diaries of urban South Africa, by Beatriz Leal Riesco

Between the paper and the wall

Neus Miró

CC BY-SA Ciara Quilty-Harper

At a time when digital technologies are globally displacing the analogue, the work of William Kentridge can, in terms of its realization and visualization, be seen as a tribute to everything manual and obsolete, while still being contemporary.

We associate the appearance of digital audiovisual products with a clean, polished, well-defined presentation, and their realization with the drawing directly on screens, then processed by production and editing programs. And while this is necessary in Kentridge’s work, his animations are characterized by their chaotic, unstable, imperfect appearance, where the tactile and manual prevail over the digital and the mechanized.

His animations begin with a piece of paper and charcoal or pastel, white and black predominate, and he occasionally add colours like red and blue if the story requires it. The line comes to life before our eyes, drawing the scene. Instead of being made up of thousands of drawings, as in the traditional practice of animation, Kentridge’s films consist of hundreds of moments in the evolutionary process of a small number of drawings, each of which corresponds to a scene, and each drawing is photographed, to piece together the film.

In the final assembly, before the spectator’s eyes, the drawing grows out of nowhere, fades away and is transformed, and another appears in its place. The process of making it remains visible, introducing a spasmodic effect that enables the viewer to perceive the spatial and temporal dissonances of the drawing instead of creating an illusion of fluid, harmonious movement.

Kentridge’s simple, immediate drawings rebel against the anonymity and homogeneity of contemporary representational languages. His drawings combine with music and subtitles, recalling silent films, while his presentation uses contemporary techniques of video projection and installation.

Kentridge’s cinema contains constant references to the past; in its scenes we see telephones, typewriters and gramophones, but also computers or sophisticated machines, underscoring the feeling of belonging to a kind of cultural “periphery” of Europe.

For those living far from South Africa, Kentridge’s work offers a gateway to the reality and complexity of life in that country, away from the visions offered by the news and the media, and it does so through intimate, personal narratives, combining drawing, movement and music.

Art and colonial memory (or forgetting)

Aída Esther Bueno Sarduy

CC BY-SA Ciara Quilty-Harper

The wound and the scar cannot exist at the same time. Talking about the colonial scar would imply having already travelled the path of memory without skipping a step, and it is during this walk that the wound would have closed. It would also mean walking history with the involvement of everyone, without overlooking the places of horror, of inhumanity, of what cannot happen again, and, during this walk, talking about the possibility of a different world, immersed in a dialogue without impositions or absences. Without the aid of plural memory, the colonial wound cannot close. Everything that covers over that wound will be mendacious, ephemeral and precarious.

Artistic productions have a lot to say in relation to this fragmentation of memory. One of the most interested and nefarious achievements of colonialism has been to produce a type of art at the service of power, disseminating alienated, prejudiced and racist aesthetic imaginaries. Colonialism appropriated art and used artists to produce these distorted representations of “others” and, at the same time, produce an aesthetic that glorifies the bodies, the history and the memory of the victors. However, art can also and must serve to challenge the materials that have shaped fragmented, obstructive colonial memory. Art can and must manipulate this colonial scar, uncover the wound, and even use this very wound as material to produce something that cannot be corrupted, covered up or silenced. It is in this sense that the work of William Kentridge (Johannesburg, History of the Main Complaint) explores the memory of horror and uses pain as raw material, questioning even the legitimacy of this appropriation of the pain in order to produce art. But in the face of wounds as deep as those of South African society, which have not yet had time to heal, art can be a witness to that pain and also a catalyst for a reparative process, although to do so it has to probe that painful, traumatized collective memory.

Unlike what history has repeatedly done, art can and is in a position to offer something different; artistic productions do not have to obey past or present colonial-imperial requirements. Art can serve to conceive other worlds, invent the future and re-examine the past without exclusions; it can cut loose, manipulate and subvert aesthetic codes, give them all the twists of which imagination is capable, accord them other meanings, place them in a different light. Artistic productions that ultimately ask other questions and do not fear the answers can and should be created.

Art as a scourge of forgetting, of exclusive memory, of imperial-colonial and racist preterition is possible. An art that dismantles the scaffolding of oblivion and forgetting is a necessary art, an art that breaks free of colonial memory, that opens that scar, that expunges, cuts free from all prejudices, be they aesthetic, of class or of race, is not just necessary but urgent. And artistic productions that do not aspire to the legitimacy granted by the institutions created by colonialism, that reject the patronage of the power that kills, denies and finances the oblivion of otherness, are something that is absolutely necessary.

Being a narrator is not enough

Lucia Piedra Galarraga

CC BY-SA Ciara Quilty-Harper

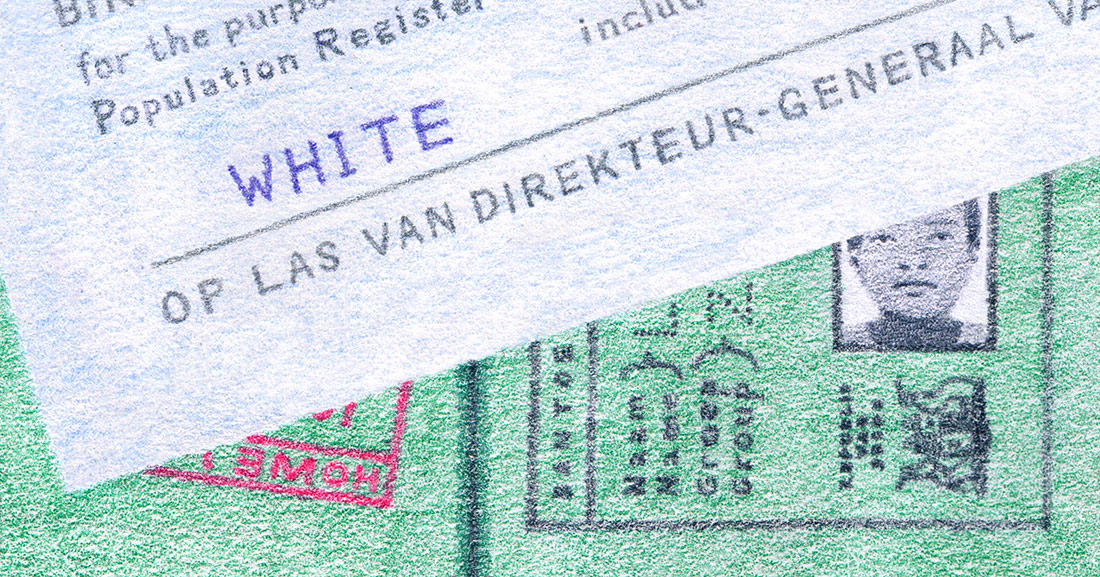

Draw-erase, draw-erase seems to be the dynamics of a grammar of representation that does not know how it is going to be said, or that knows that it is going to say something unpronounceable. Does this productive martyrology or almost sacrificial gesture of starting and starting over, frame by frame, the outline of bodies—some blurred, others defined, some far in the background, others in the fore—also speak of a phantom of guilt that does not detach William Kentridge from his privileged position as a white man of Jewish descent, articulating a correlation about Apartheid legally formalized in 1948 and an act of flagellation based on the urge to destroy what we don’t want to listen to, face, see, hear? For Kentridge it is hard to imagine a new South Africa, and he decides to free his works of the task of expressing a direct political opinion. But since Apartheid happened there, was set in a certain time, was spoken in Afrikaans and operated on very specific bodies, the details of the pain and the intimate lives represented become spectacle, stage, and nothing is so painful. To my eyes, as a woman racialized as black, he cannot escape, and the viscosity of his ambiguity bothers me. The historical episode is whitewashed by this act of ignorance, in another round of reaffirmation of sentimental colonial discourse.

This sentimental colonial discourse that cries its pain with a semblance of anti-racism places Felix and Soho in the arid mining faces of Johannesburg. This is their stage. Among images of X-rays, ultrasounds and scans. Built in the apparent poverty of coal, combined with allegories, extraction shafts, mines, fences and pipes. All elements of a topography that unites face and landscape in what Deleuze and Guattari called an “abstract machine of faciality”, which, simplified, explains the universalization of a white face/landscape by means of which everything is read and related. It is, then, no coincidence that the protagonists of Drawings for Projection are white and male, and that they wander through this relief where the black body fades into the landscape, melts into the ground, is an amorphous mass, a background voice, no more than an anguished presence. Distressing and worldless. It is a disturbing object that is difficult to manage.

If we think of the image as a discursive device in Kentridge’s work, we see that this management of the black body has branched into a physical erasure (in the use of the charcoal technique), a psychoanalytic erasure (in the substitution of one face by another, black by white) and a historical erasure (allegories of the Shoah are superimposed on the plot of Apartheid). And this is the operation of colonial thinking that translates into culture, into a drama, updating the colonial mechanics of irreconcilable differences. In this sense, Kentridge’s discursive device—which is meant to be unfamiliar, not associated—falters when we ask, alongside Fanon and Mbembe, what stories are created for those who produce them by these images of the black body, called upon to be a body without world, blurred, ghostly, rewritable? Or when we allow ourselves to be challenged by Grada Kilomba when she asks who can speak, who has a voice in what is said. William Kentridge has not survived thanks to his failures, as he claims; he has done so on the basis and with the support of a colonialist narrative. Kentridge is not anti-racist.

Filmed diaries of urban South Africa

Beatriz Leal Riesco

CC BY-SA Ciara Quilty-Harper

How can we weave a historical tapestry in which personal stories and national struggles are juxtaposed without hierarchies or assertions, creating possibilities for peace and reconciliation, without avoiding trauma, misunderstanding or impotence, breaking with the primacy of conventional linear narrative and embracing the excluded, artistic practices and minor genres? In Sea Point Days (2008) François Verster dives into the detritus of history, fearlessly facing the losses shared by the South African population to create bridges that overcome, bringing it to the fore, an emotional distance founded on violence and oppression.

Sea Point is the Cape Town suburb that gives its name to a creative audiovisual essay by Verster, Coetzee’s prize student, who paraglides from Table Mountain to become a witness to and actor in a district on the shores of the Atlantic where, in five instalments of an unfinished letter, he tells the personal stories of women and men, residents around Sea Point Promenade and its saltwater swimming pools. Taking water as his aesthetic leading thread (“Water is love and life. Without water, there cannot be life and there cannot be love”, says a pool maintenance technician and would-be social anthropologist), Verter refuses to lecture. Instead, observing and respectfully approaching his protagonists, he weaves statements with family and historical archives that, guided by an elegiac soundscape, present the complicated heritage of apartheid in the contemporary existences of several South African generations.

From the homeless being ejected to revitalize the area, through the celebration of Ramadan, Jewish ceremonies and daily dog-walking, to the activism of Afrikaner elders determined to prevent the construction of a shopping centre and luxury hotel on the seafront promenade of multiracial encounter that is Sea Point, Verster regales us with an exercise in sensibility and a juggling act of attention to the inhabitants of a changing urban space to which, like Kentridge with his native Johannesburg, Verster returns time and time again in his work.

Situating the 11 instalments of Drawings for Projection (1989-2020) in this tapestry of post-apartheid South African audiovisual creations such as this one expands the scope of Kentridge’s meditations, leading us to reflect on the future role to be played by South African artists with works that delve into complex layers of memory, in profound connection with the people and the changing urban spaces.

Leave a comment