Abandoned Amusement Park | Matt Gribbon | CC. 0

On how the author knew where the Angel of History was really heading. An exploration – which he already sketched out in his last novel, Trilogía de la guerra– into how, in a social environment that has gone beyond postmodernity, artists and thinkers are recycling the remnants that society discards in order to produce their works. We are publishing, courtesy of Galaxia Gutenberg, a translated advance excerpt from Teoría general de la basura, a book set to be published in October 2018.

In 1920 Paul Klee painted the watercolour Angelus Novus.

Angelus Novus. Paul Klee, 1920 | Wikidata | Public Domain

Shortly after that, Walter Benjamin, on one of his recurring urban walks, saw a print of the picture and bought it. Every night he looked at it carefully and on one of those observations he believed that in that angel he could see the Angel of History and, by extension, the allegory of the historical moment in which the West found itself immersed at that time: progress as the ultimate horizon. This idea, as we are aware, was recorded in writing by Benjamin thus:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread.

This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

So the Angel of History is looking toward the past – towards the wreckage of the past that gradually piles up before his eyes – but at the same time he is propelled – backwards – towards a future from which he cannot escape; a future that is none other than the embodiment of progress.

This paragraph, which during the course of a century has been subjected to all kinds of interpretations and reutilizations, gives History – History with a capital letter – a sentimentally ambiguous value; it is pessimistic from the point and the hour at which progress, however promising it may seem to us, is not exempt from contemplating what, destroyed, we leave behind us. And it is optimistic when it comes to say to us that, even if with our backs turned, we are advancing towards a future of promising discoveries.

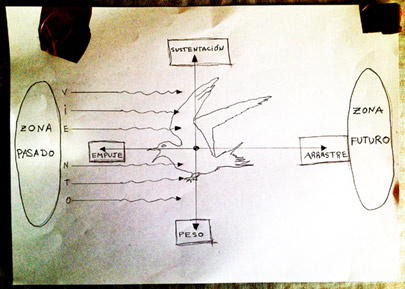

But anyone with any knowledge of aerodynamics will know that if the wind – the storm in Benjamin’s text – frontally impacts the wings of a bird, the bird will be raised and displaced in the direction opposite to that in which the wind is blowing, in other words, exactly the opposite direction to that postulated by Benjamin.

Angel of History | © Agustín Fernández Mallo

As can be seen, the Angel of History not only looks towards the past (past zone) but is also directly heading towards the past. That force, technically called thrust, takes him towards the place in which, therefore, the wreckage is found, and under no circumstances towards the future or progress. Which all implies that, sooner or later, the Angel will collide with the wreckage and, if we are talking about the Angel of History, what will happen will consequently be the end of History. Or maybe not?

As I don’t know whether I have made this clear, I will try to explain it in a different way, using a simile of a theatrical or cinematographic nature, which I am splitting into three parts:

- When in a film, or a television series, or even a first-generation reality show, the actors drink whisky, in reality they are drinking tea, and when they drink gin in reality they are drinking water, or when they are eating a bowl of soup, in reality they are not eating anything. And the viewer knows it. This, depending on each specific situation, lowers the level of reality and increases that of the simulation of that reality. At the end of the 20th century this, in general terms, was called postmodernism.

- The second possibility is the same as the first, but with the opposite sense: when the actors drink tea, what they are drinking in reality is whisky, when they drink water what they are really drinking is gin, when they drink Coca Cola what in reality they are drinking is a rum and coke, when they eat organic food what in reality they are eating is products made with trans fats, etc. And in this case the viewer does not know it (or only the most informed ones know it). This inversion with respect to the first case turns out to be the door to what we can call negative simulation, typical of an era that came to be called modernity, and that as its name indicates is prior to postmodernity.

Let’s just delay the explanation of the third position for a moment.

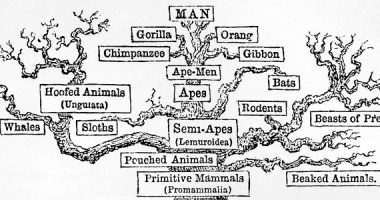

What differentiates these first two postures, as we know, is an attitude, which is aesthetical and political. The postmodernist posture generates its historical wreckages through beautified simulations, prepared ad hoc and over thematised. Let’s think, for example, of theme parks such as Port Aventura and Disneyland, or of parallel realities such as Las Vegas, which “pretend” to drink whisky when what they are truly drinking is tea, and exemplified in the figure of the mascot or the “mascotisation” of the world. The second posture is that of modernity and through the construction of the heroic epic, it generates its wreckages through simulations that play with the abject, with a pose that seeks to get to a supposed bottom that hides all those “truths” that under the lens of traditional morality are no more than materials of poor taste or waste – let’s think of the pilgrimages to Auschwitz made by tourists, who pretend they are drinking tea when what they’re really guzzling down is whisky, or, to look no further, let’s think of the use given to symbols such as Picasso’s Guernica. To put it another way: the goal of postmodernism was to play with traditional morality by way of an irony that puts into play the true/false – i.e. it appeals to play and seduction. In contrast, modernity tried to beautify the rubbish that, by definition, traditional morality spurned or hid, and for this it availed itself of subcultures that appealed to essentialist character values: faithfulness, nobility, the “authentic” or the truth.

Both attitudes, through their respective and opposing simulations, built up and revered their own wreckages. Are these wreckages the ones that, according to Benjamin, the Angel of History would observe today as soon as he moves away from them?

The 1:1 Scale

The third possibility, the one still left to tackle, is the one that interests us here. It is all about what we can call the 1:1 scale, and it is a very special kind of simulation, to all outward appearances sterile, that could be described thus: when the actors drink whisky they really are drinking whisky, when they drink tea they really are drinking tea, when they drink water they really are drinking water, and so on. That, in appearance, is quite simply the factual, what is happening tout court, the phrase or text that, for the same reason, lacks any author and any descriptions. There will be no shortage of people who will say that this case is simply and plainly Reality or the truth, but it is not; it is what is real, it is what there is of real in reality, in other words, the conflict implicit in all images, in all utterances, in all texts, and that conflict today can be generated through this special class of simulation, the 1:1 scale. The capacity to generate non-redundant reality originates in this case from the legitimate doubt and bewilderment that overcome the viewer: “If when they drink water in reality they are drinking water and if when they drink gin in reality they are drinking gin, why is all this presented to me in the form of a film, of theatre, of a performance?” What then appears, thanks to this radical doubt, is a hole, a distortion of reality, an anomaly that dynamites the order of things and opens up the possibility to non-normative discourses; that conflict is what I call The Real. In other words, in between the two simulations of reality that we had used – the modernist and the postmodernist – another simulation appears installed at the frontier, in the unstable balance that mediates between the two, in what until now has been rejected as mere debris, because it apparently seemed to be inane, but that however, with the known representations already exhausted, turns out to be the door to be explored.

Thus, we embark upon a new reading of Benjamin’s text, to say that the Angel of History is heading straight at the debris of the past, to that which other simulations hid: the 1:1 scale, which in its utopian aspiration to achieve The Real generates nonetheless the closest approximation to the narration of our present, since it problematizes it. To put it another way, it was not necessary to resort to a representation of reality – neither a modernist nor a postmodernist one – for this representation to exist; it happens, it cannot not happen: even in the most realistic of aims, representation appears.

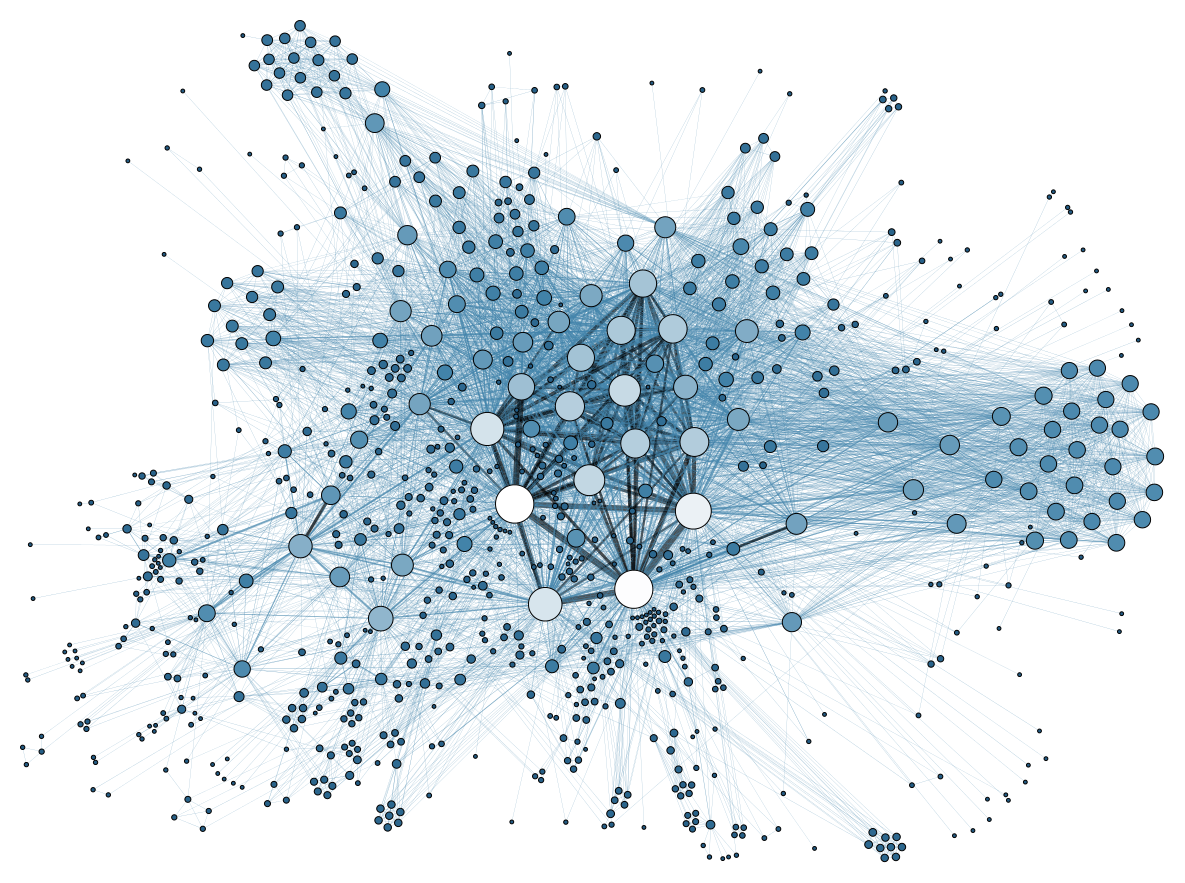

Benjamin’s text said to us: “The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed,” to then tell us that he could not. So, let’s postulate that now he can, and he heads directly towards the aforementioned dead. To the contrary of what we thought, the Angel of History is not seeking today to build a future, nor to mourn a past, but, first and foremost, to work on the 1:1 scale of the ruins left behind by old representations. These, and not others, are the foundations on which, in my opinion, narratives today must be built: what elsewhere I have called complex realism, which is realistic since it is founded on the real, on the scale of 1:1, and it is complex since all that contemporary fabric can no longer be structured in a tree or in a hierarchical way, nor even a rhizomatic way, but in a networked way. And I am not referring to the Internet network but to the thousands of networks that are analogical, digital, or mixtures of both, in which we are absorbed.

Social Network Analysis Visualization. Martin Grandjean, 2014 | Wikimedia Commons | CC-BY-SA 3.0

As will be seen later, the aim is to try to rescue things and their representations from the “prison of language” into which they had supposedly been thrown by continental philosophy, and conceive narrative reality as a system that is not solely an objective physical component with a life independent of the human being (in the style of the naïve realism of some radical positivists such as Sokal, or other moderate positivists such as Graham Harman), nor solely a construction of language (in the style of Wittgenstein or Derrida), nor either solely a socio-political construction (in the style of Bourdieu). Rather, it is a complexity in which all these fields come together, and each object, each narrative or happening is, in itself, a complex network. Authors such as Michel Serres, Bruno Latour and Manuel de Landa will be more closely linked to our pages.

(fragment from Teoría general de la basura, Galaxia Gutenberg, October 2018, original in Spanish)

Leave a comment