Radio wardman Pks. Pool, 7/10/24 | Library of the Congress | Unknown use restrictions

Fiction, as well as offering a series of methods and protocols for understanding information, can be understood as a tool used by hegemonies to perpetuate their power over our conception of the past, present experience and envisaged futures. Today, the large technology corporations make use of fiction to impose certain visions of the future that are aligned with their interests, and over which we apparently have no power.

This story starts off with a monster – the spikes on its back stick through its red cape and its arms are hairy, thick and rounded off with huge claws. This being is the reason why a community dares not to leave the confines of its village. The villagers enjoy a peaceful life as long as nobody goes too near the forest, which is home to that which “we don’t speak of”. Beyond the trees, a fence separates this Amish village from a world of highways, consumption and individualism.

In The Village – the film based on this idea – the beast is what guarantees the social order. The monster is a work of fiction made up by those who govern the village with a specific objective in mind. This myth both creates and guarantees the preservation of a way of life in which a small group of people makes decisions for all the rest, keeping them tied to a reality based on an idea of what is desirable.

In the same way, the global, connected contemporary culture of which we form part has its own hefty catalogue of fictions. For example, those that depict connected cities in which wealthy Caucasian human beings living in developed countries talk to machines that understand them instantly, using autonomous artificial intelligence at the service of efficiency and comfort[1].

What do these two works of fiction have in common? Firstly, both were created intentionally by a hegemony to maintain its power. Both aim to perpetuate a social order – one implemented by the leaders of the village, the other by the large turbo-capitalist technology corporations. The fantasy of the first draws on the past to project a future that resembles itself, while the second aims to structure the future, to convince us that “the future will be like this” and no other way.

In both cases, the fictions, espoused by the majority, structure people’s individual and collective existence. They make it possible to comprehend a certain order of things – they establish what is desirable and what undesirable, distinguish the possible from impossible. They oppress through an illusion of reality.

The first one refuses to accept that technology is related to progress (the fiction seeks to contain possible socio-technological trends). The second refuses to accept that technology and progress might not be directly related. One avoids the implementation of capitalism, while the other capitalises and commercialises the future.

The twisted currents of fiction

What we generally understand as fiction is a simulation of reality played out in media such as film, literature, videogames, comics or theatre. Today, this categorisation seems natural enough, but we can trace back its genealogy. The advent of the modern era brought with it a new roadmap of knowledge divided by the meridians of religion, science, fiction and reality.

If we focus our attention on the media, with the popularisation of the printing press, each of these categories developed a series of discursive protocols and channels of distribution that helped to distinguish them from each other. In this way, certain frameworks of understanding were established that dictated what should and should not be considered as truth.

Today, these containment walls are beginning to crack in a media ecosystem in which news is not necessarily based on real events (the slippery phenomena of post-truth). Here, what we had previously agreed to call fiction is bursting out of the channels along which it has traditionally flown (films, novels, etc.) to tarnish the legitimacy once enjoyed by the press – the media responsible for helping us to understand reality.

Techno-capitalist fictions

Money, nations, private property, romantic love, gender identity or the idea that progress and domination of nature are fictions – these are cultural constructs that order our relationships and maintain a certain social stability. They have an impact on our wellbeing, the places where we live and the superior rights and powers enjoyed by certain individuals to the detriment of others. They are contingent, consensual narratives that have ended up being institutionalised into social realities.

These frameworks of understanding begin to make sense when they are placed within a certain socioeconomic system. In this regard, Richard Sennett explains that “modern capitalism works by colonising people’s imagination of what is possible. Marx realised that capitalism had more to do with the appropriation of understanding than the appropriation of work”. In a similar vein, Frederic Jameson highlights the absurdity of the fact that it is easier for us to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

The tech industry – colossal, frenzied and monopolistic – also spreads its own fictions. In the same way as the monster in The Village, corporate fictions express the desires of those who hold power and persuade us to share them. In the present, they offer us other ways of managing our time, of affecting and being affected, of what we do and do not consider work and leisure, and ideas around closeness, comfort, security and efficiency.

However, these fictions not only act in the present, but they also work to colonise our imagination of the future. By describing what the future holds, they degenerate an inertia that drags with it different agents (governments, start-ups, universities, distributors, communication agencies, etc.) that mobilise their current resources to turn this desire into reality. The techno-capitalist elite, via channels that are supposedly non-fictitious (specialised journals, mainstream press, academic articles and essays) envision realities that do not yet exist, but which are presented as being unquestionable.

Here, fiction acts as a lubricant between different emerging scenarios (those which may come into being) and stable scenarios (those which end up existing, but which could have been otherwise). This negotiation becomes evident, for example, in the ever-changing relationship between people, machines and the systems that manage power, as corporate socio-technological fictions cast on our future the long shadow of constant delegation, the growing dependence of connected systems, flexibility, the value placed on our behaviour and constant vigilance.

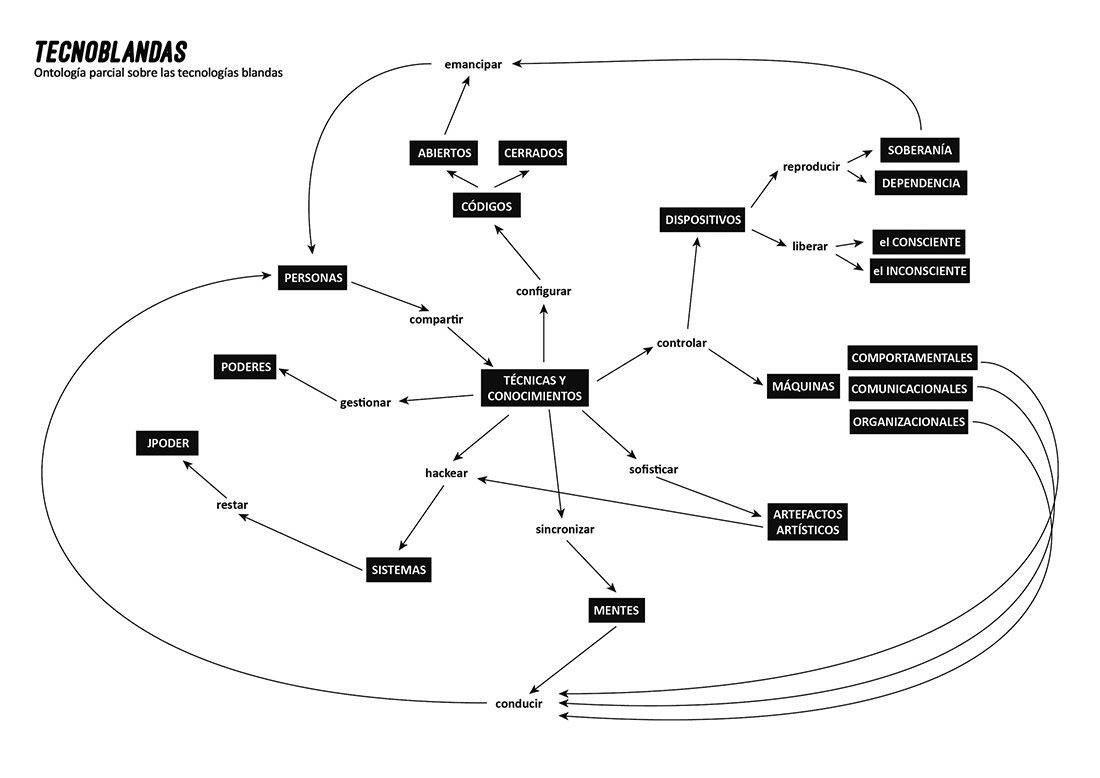

Ontology of Soft Technology (in Spanish) | Tecnologías Blandas | (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Power: tactical, strategical fiction

At a time in which the complexity of the world seems inversely proportional to our capacity to understand it, conceiving fiction to be a semiotic-material object may perhaps be useful. If we look at the fictions disseminated by institutions such as the market, the church or the heteropatriarchy, fiction appears as an element which comes into play to create a virtual illusion of reality which, through repetition, ends up consolidating itself as the oxymoron of an absolute and contingent truth that becomes a kind of symbolic infrastructure. One which, depending on hegemonic interests, defines the limits of our possibilities and guides our perceptions in the same way that a dam regulates the flow of water along a river.

But as well as meanings and behaviours, fiction also affects things in and of themselves. Established fictions materialise in cities, homes, vehicles and borders, but also in systems of interaction, financial products and labour regulations.

We therefore see that fiction can be understood as a trope – a rhetorical figure whose original meaning has been diverted along another path – which allows us to probe into that which is presented to us as being real. In effect, fiction is used as a means of control (the monster in the red cape is basically a metaphor, for example, for the behavioural constraints raised by deadly sin in relation to the reward of heaven or the punishment of hell, and which are promoted in favour of the interests of the church), and in this sense, it can also be considered as a form of soft technology – those which affect behaviours and attitudes and which can be used to seduce, communicate or generate fear or trust.

Reclaiming fiction

Using the idea of fiction as a radar for certain types of social control, we might be able to identify how fictions reach us, what they tell us, who creates them, what shapes they take, what they omit and what their purpose is. Basically, to focus on the underlying policies of these narratives and pay close attention to the media through which they are channelled, as they affect the way we coexist with other people and our relationship with ecosystems, companies and technologies. They play a part in defining the limits of what we understand as humans, living beings, users, consumers and citizens.

Perhaps, then, we can continue reigning in our credulity and generating tools to understand and intervene in the powers that govern us. Being aware that the large corporations are telling us stories will make us a little less credulous and give us tools to prevent us from uncritically accepting future scenarios imposed due to commercial interests.

But more than this, we must also be able to create counter-fictions. Fiction is a tactical technology that opens up alternatives and escape routes in a deeply unjust and unequal world that we accept as if had no power to change it. By using fiction, we can open our imagination to other, more respectful worlds, discover places that are uncolonized by capital and generate spaces where difference can exist in all its irreducibility. In short, release the power of fiction to reenchant reality with the whisper of possibility, free of the restrictions imposed by the markets and institutions that govern us.

[1] In his article titled Injusticia algorítmica (algorithmic injustice), David Casacuberta explores an alternative scenario to that promoted by the technology corporations, to highlight the discrimination reproduced by so-called intelligent systems.

Fiction as method, edited by Jon K Shaw and Theo Reeves-Evison. Sterngberg Press

Futures & Fictions, edited by Henriette Gunkel, Ayesha Hameed and Simon O’Sullivan. Repeater

Fixtions: ficciones colaborativas para intervenir desde la especulación en realidades emergentes, Andreu Belsunces, in Temes de disseny, Elisava.

Narratopías de futuro: el agotamiento de lo posible, Laura Benítez. CCCBLab

Futuro(s): desde dónde, hacia cuándo y para quién. Andreu Belsunces, in Design Does, Elisava.

Leave a comment