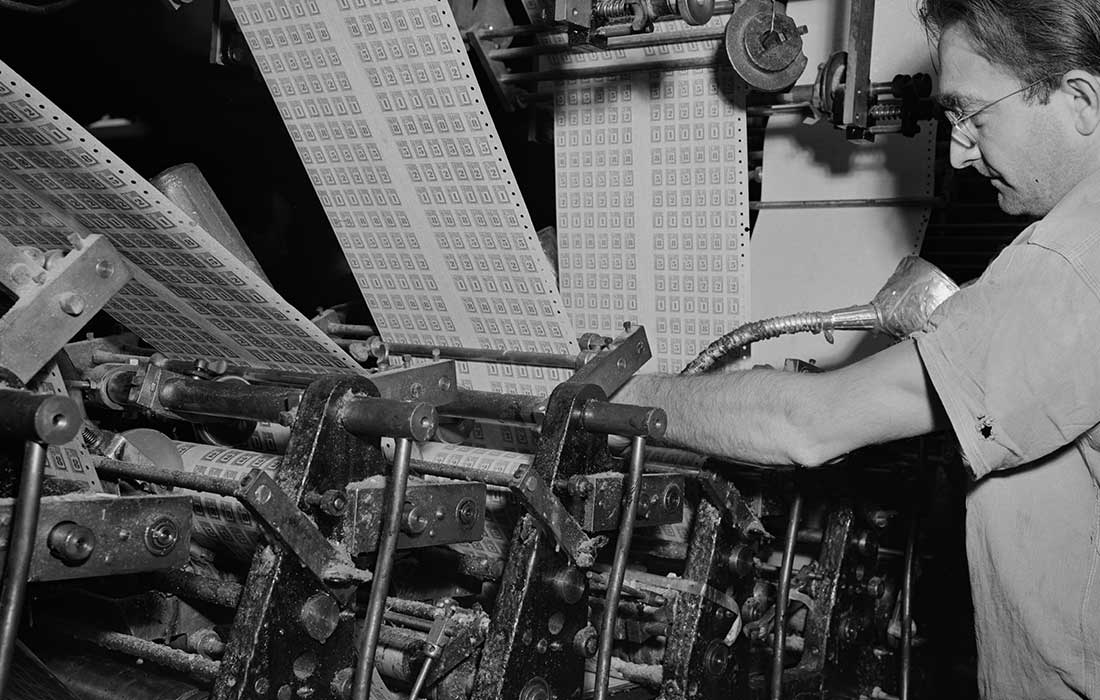

Printing war ration book. Hudson County, New Jersey, Estats Units. 1942 | United States Office Of War Information. Library of the Congress | Public Domain

Eco-publishing is a way of producing publications in accordance with the principles of sustainability. Presently, almost 10% of what we read is in digital format, near to 100% of paper publications are produced using electronic equipment, and the energy footprint represents 7% of total greenhouse gas emissions. This is why we are looking into the environmental impact of digital publishing based on the conclusions of the latest Ecobooklab organised by Pol·len edicions and the LEITAT Technological Centre.

Publishing books based on environmentally-friendly criteria means rethinking the entire publishing process, from initial design to marketing. Eco-publishing is a way of producing publications in accordance with the principles of sustainability. Of calculating, minimising and communicating the environmental impacts of publications. In the same way as paper book production, the production of digital books must involve the calculation, minimisation and communication of impacts. And once these have been reduced, reduced and reduced again to the minimum possible levels, offsetting measures can be contemplated, although these should never be a green pass for failing to reduce impacts. Finally, eco-publishing also requires a consensus between the entire book ecosystem and its various value chains.

Digital publishing

When talking about the environmental impact of digital publishing, there are several factors that need to be taken into account. Firstly, almost 100% of paper publications are produced using electronic equipment, meaning they can also be considered as partially digital – both their manufacturing process and the way they are used involve elements of digitalisation. For example, the design phase of a paper book represents 9.6% of the book’s environmental impact. But it is at this moment, when the decisions are taken regarding the product design, that it is possible to reduce its impacts. And this is the purpose of the BookDAPer.cat calculator – to calculate the environmental impact (carbon footprint, consumption of resources and other environmental indicators), help to take measures to minimise it, and inform the reading public by means of the bDAP label.

Meanwhile, reading on digital devices represents near to 10% of total reading around the world, and is constantly growing. According to a study carried out by Libranda, the e-book business in Spain grew by 37% during 2020. The profile of person who opts to read books on digital devices is highly varied, but e-books have been seen to attract new people to the habit of reading. In the first scene of the film The Russia House someone mentions the existence of an audio fair in Moscow. “Audio fair?”, asks one of the characters. “Cassettes”, they reply, “Books of the bloody future”.

New technologies are often seen as a force to displace the technologies that precede them, and this has certainly often been the case. But what would happen if we shifted away from this perspective and allowed the digital and analogue worlds to come together?

The environmental impact of digital publishing

Nowadays, nobody can deny that digital technologies have an environmental impact, one that is growing all the time. According to the report Click Cleanpublished by Greenpeace, in 2017 around 7% of total global energy consumption resulted from what some people call digital capitalism. If the internet were a country, it would be the 6th biggest polluter, and if we add all the emission generated by the electronic devices we need to browse the web, it is by far the industry that generates most emissions.

The researcher and artist Joana Moll warns that: “despite the notion that the internet is a cloud, it actually relies on thousands of servers and undersea cables”. According to her project CO2GLE, Google emits 500 kilograms of GHG (greenhouse gases) every second. This is equivalent, for example, to the entire first edition (1000 copies) of the book I aquí, qui mana?by Laia Panyella, published with the llibre local (local book) seal on 100% recycled paper.

According to the journalist Justin Delépine, 45% of the digital energy footprint corresponds to the manufacture of devices and 55% to their use. 5G is the latest generation mobile network that could multiply the volume of data transported by ten, although in theory it is between two to three times more energy efficient than 4G. However, according to Delépine, “5G will allow a dangerous acceleration of data consumption”, as the rebound effect will come into play – consumption increases because it is less expensive or more efficient (see the Jevons paradox). It also carries the risk of speeding up obsolescence – while at the moment people change their devices every two years, with 5G we’ll all need to buy new smartphones, generating more production and impact. Obsolescence (whether programmed or not, or simply perceived) is one of the environmental dramas of digitalisation.

Digital reading devices are made up of materials and components. Some of these components, for example the battery, contain coltan, lithium or other elements. The printed circuit board contains principally copper and gold, but also cadmium, tin, lead, palladium and tantalum (one of the components of coltan). The extraction of these metals has both economic and human costs. Two examples are the blood-stained minerals of the Congo (see the report Critical Minerals from Engineers without Borders) and the lithium conflict in Latin America. The extraction of 1 tonne of gold involves moving 50,000 tonnes of earth. 240 kg of fossil fuels, 22 kg of chemicals and 1,500 litres of water are needed to make one computer. To manufacture the book mentioned above took 321 grams of raw materials and 10 litres of water.

The book El futur dels llibres electrònics(the future of electronic books) offers some useful data. For example, for an e-reader to be sustainable, in other words, for its environmental impact to be lower than its paper equivalents, the owner of the device needs to read 322 books of 110 pages each. If we take the average number of books read by a Catalan reader each year as 10.9, then their e-reader would need to last 30 years to offset its environmental impact. Some more data:

- The impact of a Kindle is 168 kg of CO2, equivalent to 22.5 paper books in the US. (Source: Cleantech Group)

- To offset the impact of an e-reader device in Sweden, the owner needs to read 33 e-books of 360 pages each. (Source: Royal Institute of Technology of Sweden)

- It takes 15 years to offset the carbon footprint of an e-reader device. (Source: Carbone 4, French environmental consultancy)

- Between the iPhone4 (2010) and the iPhoneX (2017), the carbon footprint has grown by 75%.

- An iPad generates 130 kg of CO2 over a lifespan of 3 years (with 45% of emissions generated through manufacture; 49% through use; and 6% from its transport and processing as waste).

E-reader devices have a large impact produced through their manufacture, their use and their end-of-life processing. Recycling electrical and electronic devices is highly complicated and costly due to the number of components and materials they contain, a factor which negatively affects their sustainability. The same does not apply to paper books, whose impact is limited to their manufacturing and recycling, if this occurs. What is more, paper books are carbon devices.

In the case of books consumed in digital format, where should we start? By reducing the impact of their manufacturing, or their use? During the Ecobooklab 2020 the engineer William Ramírez, from The Good Plug project, took apart an iPad and an e-readerto reveal all their components and materials (case, keyboard, speakers, screws, battery, circuit boards), made of plastic, metal, etc. These pieces can be used to perform a life-cycle assessment and calculate the environmental impact of all these components and the implications of the manufacture of the two devices. The results should be available soon. Ramírez highlighted the need to lengthen the lifespan of electrical and electronic devices and to give them “a second life”, and for both repair companies and their technicians to correctly separate materials and parts so they can be reused. At the same time, the big manufacturers should work together to create interchangeable parts, like the universal battery charger.

To briefly sum up, in terms of the environmental impact of digital publishing, the key ideas are: the importance of knowing how to generate “co-existence” between the world of paper books and the virtual and digital world(s); the fact the public needs to make strict demands for the traceability of products, electronic or otherwise; not perceiving nature as something foreign and extraneous to ourselves; and not losing sight of the importance of “community” when it comes to everything pertaining to the world of culture.

The state of eco-publishing: widening the consensus

We have always said that eco-publishing requires a consensus among the entire book ecosystem and its various value chains. This consensus can be understood as a meeting point for sharing knowledge and practices that help us to take the best decisions. There are many correct ways of going about something, and product life-cycle assessment is a step in the right direction. Furthermore, ecodesign would generate not only economic, but also environmental savings.

As demonstrated in the report Lideratge mediambiental en el sector cultural i creatiu català (Environmental leadership in the Catalan cultural and creative sector), Catalonia’s book ecosystem is in a good position to continue innovating and leading the way in the field of eco-publishing. Of all Catalonia’s cultural industries, paper book publishing is the area that has taken and expects to take the biggest strides. Thanks to the appearance of innovations such as the Llibre local (local book) certification seal used by publishers who are committed to producing their books in Catalonia; the growing number of paper certifications (we already make extensive use of FSC-certified and recycled paper in our publishing house); and the bookDAPer.cat carbon calculator, we are able to implement decisions that reduce the environmental impact of our books. The COVID-19 pandemic has sped up the processes and dynamics that were already underway, including the urgently needed response to the climate emergency. Now we need to decide how to apply these three measures to digital publishing… and we are sure to find a way.

Lara Santaella | 31 August 2021

Hola, el estudio que citáis —acerca de cuánto tiempo tiene que durar un lector de ebooks para ser sostenible— es incompleto y carece de bases contrastadas.

No seré yo quien defienda a individuos calvos que sueñan con ser la version Hacendado de Lex Luthor, pero creo que sólo con el “paseíllo” que he hecho estos tres últimos años en mudanzas (acarreando un Kindle en vez de diez cajas llenas de libros de un lado a otro de la geografía española) ya he amortizado la huella ecológica de mi aparatejo.

Y eso por no hablar de que pocos son los pisos disponibles y asequibles donde quepan libros de papel…

Ariel Wilson | 14 March 2022

Very Good Article

Leave a comment