Fragment of the cover of Pasolini by Davide Toffolo. Image courtesy of 451 Publishers.

“I’m not one of those intellectuals who read comics,” wrote Pasolini just two years before the publication of Umberto Eco’s Apocalyptic and Integrated in 1965, which made comic strips culturally respectable around the world. In this sense, the Italian filmmaker was swimming against the tide of most of his contemporaries who brought comics or “fumetti” into the adult realm from the mid-sixties onwards through magazines such as Linus and the Lucca Comics & Games conventions.

Paradoxically, they had all grown up reading the comic strips by the great master Antonio Rubino that had been regularly published along with classic North American cartoons in the Corriere dei Piccoli since the early twentieth century, and which were responsible for European comics definitive tending to target children. Rubino – who described himself as a painter and a poet – had been a seminal influence on Federico Fellini, for example, for whom Pasolini later worked for as a screenwriter on The Nights of Cabiria and, along with others, on La dolce vita.

Fellini strongly acknowledge his emotional debt to the comics of his childhood, embodied in films such as Juliet of the Spirits and Amarcord, and he himself had written the script for an Italian version of Flash Gordon, and, near the end of his life, for Trip to Tulum, illustrated by Milo Manara. Nonetheless, Pasolini’s apparent distance from “the ninth art” was not as great as it would seem.

Twenty years earlier, during the period when he worked as a primary school teacher in Valvasone, Pier Paolo had already urged his students to create comic strips of the subjects they were studying, probably under the influence of the new Montessori schools and Gramsci’s critical pedagogy. He was thus pre-empting Hugo Pratt’s famous claim that “comics are the poor man’s cinema”.

Pasolini was probably not familiar with the many cartoons that his comrade the poet Mayakovsky had produced in the form of posters during the Soviet revolution, and – only by reserving the role of mere kids’ entertainment for comics that the fascist Rubino had conferred on them – he could ignore their political potential in keeping with the heterodox Marxism of Gramsci, who was one of the Italian filmmaker’s intellectual influences.

In the first half of the twentieth century, comics were the quintessential popular art, produced and consumed on a massive scale, much like cinema itself. It is true that the characters in comic strips represented stereotypes – a feature that has stigmatised the ninth art but that perfectly expresses the embodiment of the struggle for political-cultural hegemony in the form of concrete figures. And it comes as no surprise that in Italy comics are called “fumetti” – what we call a “bubble” –the little balloon that comes out of a character’s mouth to express his voice. The language used in comic books easily became infused with spoken language, popular expressions and even regional dialects or class jargon, a tendency that was by no means alien to Pasolini, whose “trilogy of life” can easily be imagined in comic strip version.

It was no easy feat for the Italian writer to swap his pen for a camera, and in this too he turned to comics for support. As early as his second film, Mamma Roma, Pier Paolo started to write scripts for his own films in the form of storyboards, as a preliminary step to filming. And just a few months before claiming that he didn’t read comics, he had written to the publisher of one of his books with a proposal to create one himself: This is the end of a plan for a very strange book; I have in my mind a dozen comic episodes that I would like to film again with Totò and Ninetto, but I may never get the chance because of my many commitments. Now I’ve developed the script for the last episode of La terra vista dalla luna in the form of a colour “fumetto” (drawing on some of my rough skills as a painter who quit). This being the case, I would like to gradually put together a big book of fumetti… very colourful and expressionistic… where I can gather together all these stories that are in my mind, whether or not I end up filming them.

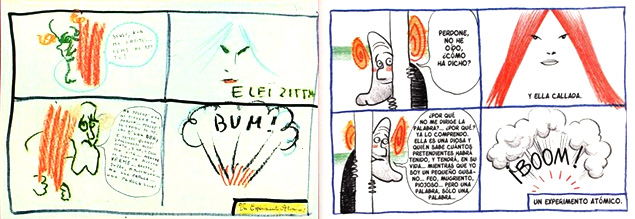

Unfortunately, Pier Paolo’s comic book was never published. But the original storyboard, which is currently on display in the exhibition Pasolini Roma at the CCCB, ended up inspiring one of two recent projects that take the filmmaker into comic books.

Storyboard of La terra vista dalla luna by Pasolini and the version redrawn by Toffolo.

After Le ceneri di Pasolini – which was published in 1976 by punk artist Graziano Origa in the magazine Contro –, we had to wait until the 30th anniversary of the murder of the communist poet in order for the world of comics to decide to turn him into a protagonist. In 2005, two graphic novels commemorated the Italian filmmaker: Il delitto Pasolini by Gianluca Manconi and Pasolini by Davide Toffolo.

The first focuses on Pasolini´s lurid murder during Italy’s “years of lead”, a reconstruction of the events that lies somewhere between drama and an investigation of the final days of the filmmaker, right up to the scene of the crime. This documentary framework lends itself to a syncopated layout in regular vignettes, often featuring talking heads that address the reader, as in a television screen.

Meanwhile, Toffolo’s Pasolini gradually turns away from this temptation in favour of a poetic presentation of the filmmaker as a human being and an intellectual figure. In this work, a character representing the author travels through the landscape of today’s Italy along with a mythomaniac who thinks he is Pier Paolo, and unearths the storyboard of La terra vista dalla luna in order to re-draw it. The Italian “fumettista” develops the themes of this graphic novel beyond the limits of the printed page in the documentary Pasolini, l’encontro, an animated concert with the rock group Tre Allegri Ragazzi Morti. On 2 July, the CCCB offers Barcelona residents the unique opportunity to participate in a workshop and lecture by Davide Toffolo. A chance to reconcile the ninth art with Pier Paolo Pasolini, a poet, a filmmaker who didn’t read comics because, in a sense, he created them.

Antonio J. Quesada | 29 June 2013

Estimat amic: li deixo un enllaç amb una referència que faig al seu excel · lent treball sobre PPP. Enhorabona.

una cordial salutació des de Màlaga, d’un adalus molt vigatà

Antonio J. Quesada | 29 June 2013

Deu… ahí va el enlace, que lo olvidé antes

http://antoniojetaquesada.blogspot.com.es/2013/06/pasolini-y-el-comic-una-relacion-curiosa.html

Equip CCCB LAB | 30 June 2013

Gràcies Antonio.

Benito | 01 July 2013

Al compás de esto: http://tiempoflamenco.blogspot.com.es/search/label/Pasolini

Breixo Harguindey | 01 July 2013

Muchas gracias por el enlace Antonio y aún más por el elogio, una pena que no andes por aquí y pudieras venir al debate, seguro que tus aportaciones serían, al menos, igual de interesantes. Un saludo

Jordi Riera | 02 July 2013

Interessant l’article. Que vagi molt bé el debat.

http://www.comicat.cat/2013/07/avui-debat-pasolini-al-laboratori.html

Antonio J. Quesada | 03 July 2013

Sería un gran honor, amics, por aqui tenemos proyectos pasolinianos que, si fructifican, os comentaré

una forta abraçada

Leave a comment