Mimeograph Room at University of Illinois at Chicago, 1947. CC-BY-NC-ND, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Over the last 20 years, self-publishing has become a mass phenomenon. Anyone can now get their book published and seen by a global readership. Due to its potential for universal access, global distribution and freedom of content, self-publishing is perceived as a challenge to the status quo of the 500-year-old book sector. Like every new paradigm, self-publishing drums up both detractors and supporters. There are those who claim this new trend empowers authors at the expense of culture, while others maintain that it is incompatible with the publishing sector. What is myth and what is reality? In order to tell them apart, we need to understand what self-publishing really entails in the current context.

Before the advent of the Internet, anybody who wanted to express their opinions, see their research published, or share their creative writing with others beyond their close acquaintances required the support of a channel that would allow them to speak to the public. This channel used to be a media outlet or a publisher.

The bottleneck

For centuries, media outlets and publishers acted on behalf of the general public, as a filter and a loudspeaker. The media selected articles according to their particular agenda, specialized publications filtered research by perceived relevance, and publishers selected manuscripts according to their literary merit and interest to potential readers. Thus, only very few authors were published, while many others remained hopeful.

This screening process still continues and it is far from infallible. One of the most notorious experiments in the book sector was conducted by the Sunday Times in 2006. The newspaper sent 20 publishers and agents chapters from In a Free State by Nobel laureate V. S. Naipaul, and from Holiday, Stanley Middleton’s 1974 Booker Prize winning novel. Of the almost two dozen publishing professionals who received the manuscript, only one agent showed an interest in one of the works, and that was Middleton’s novel. Similarly, books by such admired authors as James Joyce, Agatha Christie, George Orwell, William Golding and J. K. Rowling were once brushed aside by agents and publishers alike.

Publishing for all

20 years ago, with the rise of the Internet, users gained the freedom to express their ideas and to access the content shared by others without entry barriers or filters, other than those of search engines such as Yahoo and later Google.

The blogosphere was the first tool and platform that democratized content-publishing by providing universal, equal access. It was followed by other self-publishing tools that helped writers bring their books to the online and offline markets, and to make them accessible to readers all over the world. Never before had individuals been given the opportunity to reach such large, remote, or specific audiences by their own means.

But why do people self-publish? Contrary to popular belief, it is not a last resort for authors. Depending on their needs and goals, self-publishing may simply be the right path for many writers to get their books on the market.

Benefits of the model

Generally speaking, all of the self-publishing options available on the market turn a Word document into a published book in less time than a traditional publisher would. Authors can customize the book to their taste and make their work accessible to readers through at least one channel and in at least one format, worldwide, and they typically receive higher royalties on the sales.

The Internet also grants equal opportunities: it is a marketplace where indie authors can display, promote, and sell their books. Online global retailers like Amazon, Google Books and iBooks allocate as much space to self-published books as they do to those from legacy publishing.

New Business Models in The Publishing Industry: Abundance of Content, Forms of Access and Revenue Generation, Carmen Ospina. 2015

Testing the market

Writers must be published, if they are to be read: self-publishing allows them to test their book with both readers and publishers. Because authors retain the rights to their work, they can still send their manuscripts to traditional publishers if they wish to do so. And while waiting for a reply –which can take anywhere from several months to two years–, they might as well enjoy their first sales in the meantime.

Moreover, publishers see self-publishing as a pool of talent. Renowned authors such as Ernest Hemingway, recent examples such as E. L. James, and new voices such as Laura Ferrero all self-published their works at some stage. In 2015, Ferrero covered the cost of publishing her collection of short stories under the title Piscinas Vacías. She quickly saw it make Amazon’s top 100 best-selling list, and signed a publishing contract with Alfaguara within six months of putting her first book on market.

Environmental sustainability

Self-publishing is not only based on the popularity of the Internet as a distribution channel, but also on the efficiency of print-on-demand technology. A printed-on-demand book is only printed when it is ordered, in exactly the number of units required, and as close as possible to the buyer’s location. Thus, an author could self-publish his book today in Barcelona and a reader could acquire it in Sydney in a matter of days. Thanks to the digitalization of files and this printing modality, a single unit of the book will be printed and delivered in Australia.

Specific audience or content

Scientific treatises, memoirs, and self-help books are all aimed at very specific audiences –a particular segment or niche of readers–, who are interested in the subject and may be geographically dispersed. Self-publishing can bring this content to light and make it accessible to readers anywhere in the world.

Similarly, there are books such as public sector publications that are circumscribed within the territory where they are produced. Town halls that subsidize the publishing of works on local history, universities that publish their professors’ research, and cultural institutions that promote creative writing could well benefit from making these contents universally accessible, beyond their own sphere of influence.

Quality and culture

One of the most common problems attributed to self-publishing is that it encompasses a vast collection of works of varying quality. This is indeed true. The consequences that follow, however, are open to question: Is self-publishing really detrimental to culture and society?

Let us consider the example of the Internet. Platforms like Blogger and WordPress have empowered anyone who can write to express themselves, but they have also empowered anyone who can read to enjoy unlimited access to content without filters or intermediaries. Is there a crusade against these platforms because they host all kinds of content?

Similarly, the Internet and self-publishing are an extensive source of content accessible to society. Readers themselves decide whether they ‘like’ a particular link or book to which they have been directed. Inasmuch as the digital world provides countless more reading options than its analogue counterpart, the consumption experience tends to become ever more customized.

Meanwhile, just as a new kind of author is emerging, so is a new kind of reader: the long tail reader.

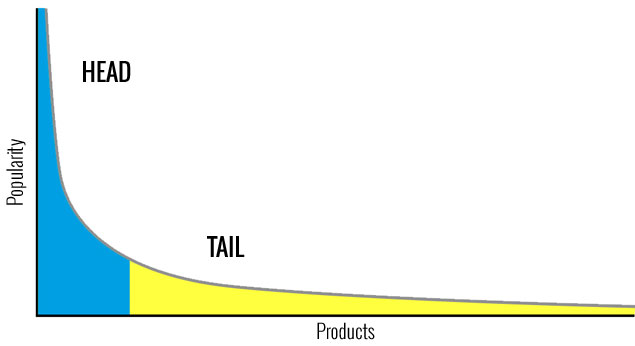

Long tail graph. Public Domain, Hay Kranen (modified)

Chris Anderson, editor of Wired Magazine, anticipated a cultural and economic trend in 2004, explaining how the classic sales model based on few products with high demand (the head of the figure) now coexists with a new model of quasi-infinite references with lower unitary demand (the long tail).

Legacy publishing has historically directed its efforts towards finding works that could capture as many readers as possible. However, these same readers may also be interested in consuming other types of content –long tail content– that is also related to their preferences: a friend’s poetry collection, the history of an indigenous community, or the firsthand life story of recovery from an illness. Self-publishing comprises these works and helps them reach their audiences.

Today, we find that the book industry has broadened its spectrum of publishing and reading possibilities beyond the mass audience model. Self-publishing provides legacy publishing with both best-selling and long tail works. It facilitates freedom of expression as it lifts barriers to publishing, and it offers society a variety of content that would otherwise hardly see the light or find its readers.

Ramona Canela | 02 March 2016

Very, very interesting.A nice option !

And very good exposition

Many thanks

Equip CCCB LAB | 03 March 2016

Thank you for your answer!

Yes, it is an unclear situation and a wide picture of the scenario it’s always useful! Although we still don’t know what will happen.

luciana Cavazzani | 13 March 2016

Artículo muy interesante. No conocia este lado de las editoriales y ha sido muy bueno aprender como funciona el mundo literario, sobretodo con todas las posibilidades que existen de publicaciones dentro de internet.

maria angélica yasenza de santana | 05 February 2017

Hola Mireia. Estoy en la mitad de una novela. Mi primer libro y me gustaría saber luego de terminarla cómo sigue el procedimiento para poder publicarla. Gracias

Leave a comment