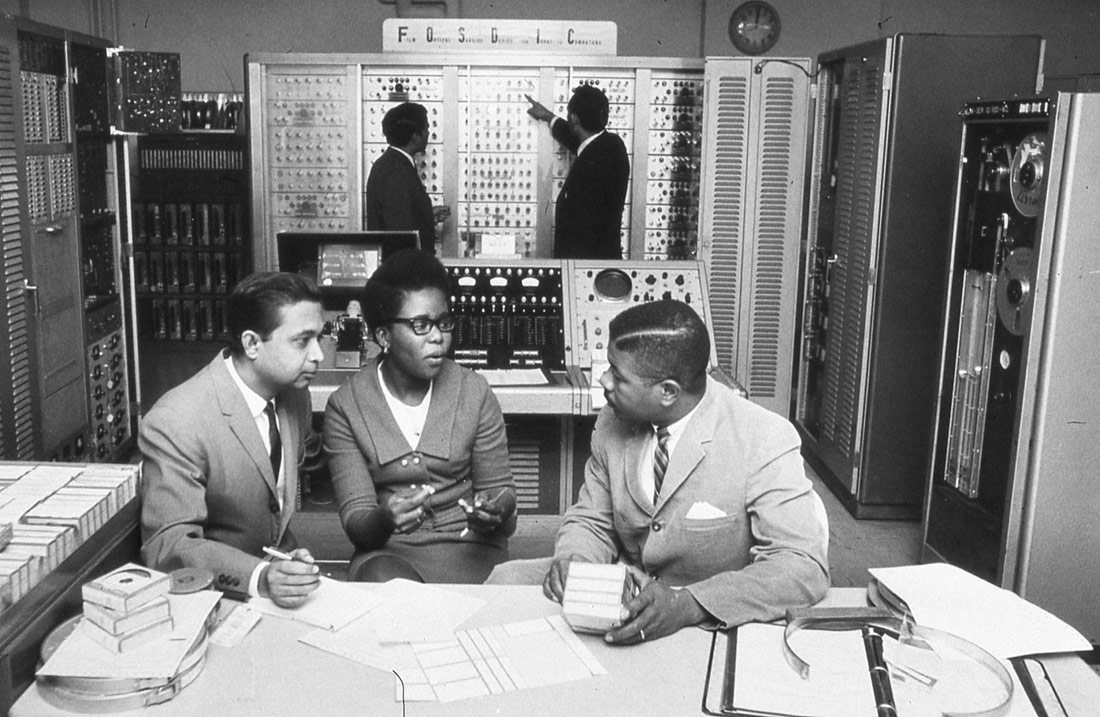

FOSDIC (Film Optical Sensing Device for Input to Computers) | U.S. Census Bureau | Public Domain

It is risky to reduce ethics to a mathematical calculation of damages and options. Machine learning algorithms make use of the context to take decisions, without any causal comprehension of the phenomena they aim to predict. Human ethical knowledge is pre-reflexive; it is not simply the conclusion of a purely rational argument, but the result of an educational process that begins in our childhood. This is a sphere of human activity to which we have immediate access, it is intuitive and the result of sharing nature and culture. This intuition at present is not reducible to algorithms, neither those based on rules and definitions, nor those based on statistics of semblance.

The judge carefully examines the reports he has received. He then consults his notes and issues his verdict: “Taking into consideration your first name, your age, the neighbourhood that you live in and your secondary school grades I have decided to hereby declare you guilty of the crime of which you are accused.”

If a judge made a statement like this, it would cause a major scandal, yet the police of Durham, in the UK, are using a machine learning system known as HART (Harm Assessment Risk Tool) to make predictions regarding who might re-offend. The programme uses correlations such as the type of neighbourhood in which the person lives, their ethnic origin (obtained based on the proxy of their first name) and school absenteeism rates to detect possible “disconnected youths” who might carry out crimes against property or people.

The problem is not in the effectiveness of the system. Even if the programme were 100% effective and got it right in all cases, it would continue to be incompatible with our idea of what justice is.

A basic intuition on which our idea of justice is based was captured by philosopher G. H. Von Wright in his book Explanation and Understanding. There, Von Wright argued that, when giving meaning to our lives, we use two different paradigms: causes and reasons. According to Von Wright, the causes explain to us why something has happened in the way that it has happened, while the reasons enable us to understand the ultimate why of something that has happened. The causes form part of scientific reasoning and explain to us in detail how something happens. The reasons are situated in the sphere of the humanities and explain to us the why of a situation, based on a human, situated comprehension, on how we understand the world and what our values are.

Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein considered that intuition in one of the aphorisms of his Philosophical Investigations, where he argues that if a judge decides to declare a person guilty, he will do so for the reasons that led him to act. If he were guided by the causes, he would always let the person go free. In other words, if we seek the ultimate cause of a criminal behaviour, we always find something: childhood abuse, mental disorders, etc. In the last instance, we can always say that the neurons of his brain adopted such a structure and formation that they inevitably led that person to commit a crime. These are the reasons for which someone acts and not the causes that we use to value the ethicality of a certain behaviour.

As I have explained in the first post in this series (Bias in a feedback loop: fuelling algorithmic injustice), today’s machine learning algorithms lean heavily on the context, and they have no kind of causal understanding of the phenomena that they are trying to predict. If, by chance, all people called David who live in a certain neighbourhood in Durham were already on record as dangerous criminals and I went to live in that neighbourhood, I would have the police at my house every five minutes, suspecting some crime. It is not difficult to imagine even, that sick of the pressure, I might end up really committing a crime.

Let’s imagine that in the future we manage to get artificial intelligence programmes capable of carrying out correct causal reasoning, something from which we are still a long way away, according to experts in the reasoning of AIs such as Judea Pearl. Even so we would still not have an AI capable of reasoning like a judge, since it would lack accessibility to the knowledge of the reasons.

The recently departed philosopher Hubert Dreyfus has argued this position coherently in diverse articles about what expert knowledge of ethics would consist of. Dreyfus insisted that in a mere discursive knowledge, of causes, on what is ethical and what is not would be insufficient for capturing the ethical reasonings of a person.

A team of researchers from the MIT uses the famous trolley problem, devised by contemporary philosopher Philippa Foot to try to show self-driving cars to take ethical decisions. The idea is that before an inevitable accident in which there are diverse options, the electronic brain of the smart car will take the most morally adequate decision: an attempt to reduce ethics to a mathematical calculation of damages and options.

This system, although it would undoubtedly be useful, does not capture all the nuances that a human decision contains. Basically, our ethical knowledge is pre-reflexive, it is not simply the conclusion of a purely rational argument, but the result of a formative process that starts in our childhood, where we have a series of personal experiences that allow us to make sense of our world. These experiences are strongly influenced by the society and culture in which we live. Our ethical knowledge is spontaneous, intuitive and immediate. It does not establish truths etched in stone, rather it is fluid and it reviews and reframes our perception of whether an action is ethical or not according to our interactions with other people and cultures. This approach is based on our basic capacity to give meaning to our environment, which needs radical autonomy that enables us to establish ourselves as individuals in the world.

Let’s see another specific example: In the year 2016, Facebook decided to remove the iconic photograph of the then 9-year-old girl Kim Phúc without clothes, fleeing from a Napalm attack during the Vietnam War. An automatic algorithm had classified it as “possible pornography” and had eliminated it from the account of a Norwegian journalist who was carrying out a study on the horror of war. Protests from the newspaper and even from the Norwegian government, as well as thousands of indignant users were necessary to make Facebook back down and finally the photograph returned to the social network.

The official response from Facebook when it insisted that it was not going to permit that photograph, was that it was complex to determine when a photograph of a minor without clothing is appropriate and when it is not. And, effectively, if what we are seeking is an algorithm that tells us whether an image is pornographic or not according to the quantity of exposed skin shown, we are not going to find anything. To understand why the photograph of the “napalm girl” is not pornographic but a denouncement of the horror of war, we need to understand many things about human nature: what gives us pleasure and what generates suffering for us; what a soldier is, what a war is, how a child feels when he sees flames raining down from the sky. All of this is left out if we simply study the degrees of similarity between the image of Kim Phúc fleeing and the photographs that one finds on a site like Pornhub.

The judge of the Supreme Court of the United States, Potter Stewart, presented the dilemma perfectly when, in 1964, upon having to decide whether a determined film was pornographic or not, he stated: “I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description [“hard-core pornography”], and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it, and the motion picture involved in this case is not that.” “I know it when I see it” perfectly sums up what I am seeking to describe in this post. There is a sphere of human activity to which we have immediate, intuitive access, the result of sharing a nature and a culture. That intuition is not reducible to algorithms, neither those based on rules and definitions nor those based on statistical similarities. But we all recognise it when we see it.

Dreyfus thought that these humanistic capacities were totally outside the reach of electronic machines. For my part I confess that I am agnostic on the question. I do not see any ontological or gnoseological reason why we cannot one day have true artificial intelligences, which rival our own human capacities, although my intuition tells me that that day is still a long way off.

But I believe that there is a clear lesson that we must consider: the development of digital technologies does not have to be guided exclusively by scientific and market criteria: we must also include a humanistic vision that informs us when a machine or an algorithm makes sense and when it is better to trust in human intuition.

Consuelo | 19 June 2018

Muy interesante y clara reflexión. Gracias

Gonzalo Génova | 11 January 2023

Un artículo excelente. Llego aquí por la referencia incluida en el trabajo de una alumna del curso “Inteligencia natural y artificial” que acabo de impartir en mi universidad (Carlos III de Madrid).

Tenemos muchos puntos en común, en mi blog he escrito mucho sobre la “moralidad algorítmica”. Por ejemplo: Conformidad con la norma (https://demaquinaseintenciones.wordpress.com/2022/09/15/conformidad-con-la-norma/) y Utilitarismo: ¿se puede calcular la felicidad? (https://demaquinaseintenciones.wordpress.com/2021/11/21/utilitarismo-se-puede-calcular-la-felicidad/).

Sobre la cuestión apuntada en el penúltimo párrafo, “No veo ninguna razón ontológica o gnoseológica por la que no podamos tener un día verdaderas inteligencias artificiales”, en mi opinión la clave para dar una respuesta negativa es esta: la pregunta no es si un ente material puede ser libre, sino si un ente DISEÑADO PARA UN FIN puede ser libre. Porque eso es la IA.

Leave a comment