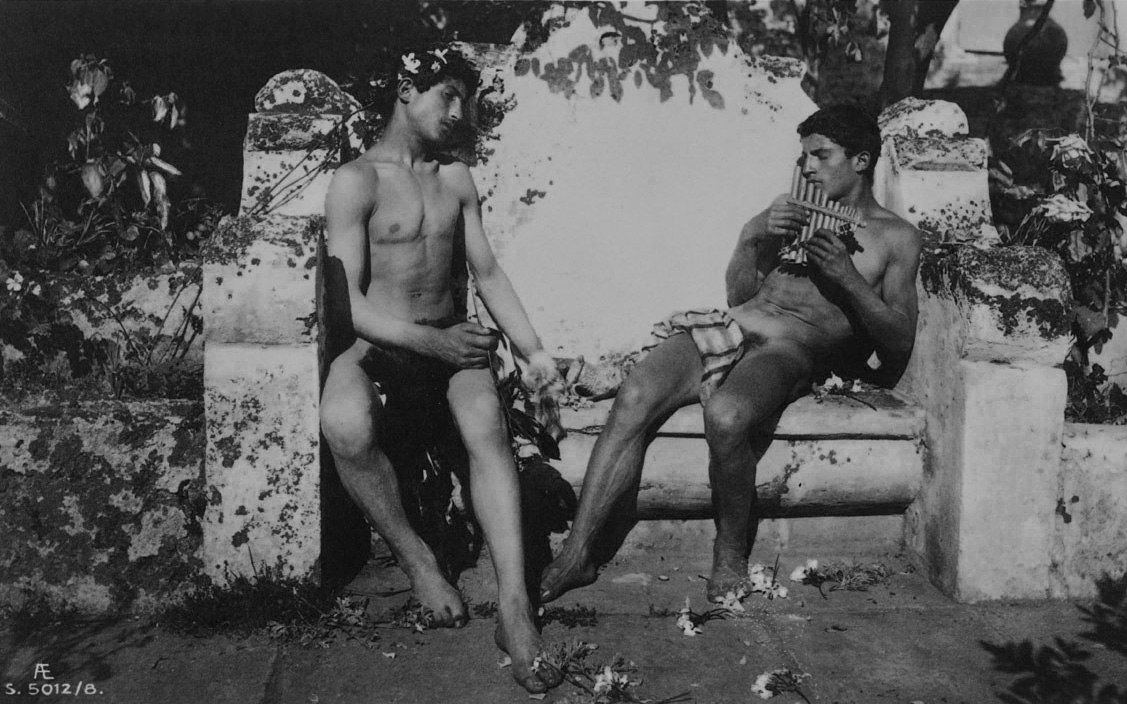

Concert of flute, 1905 | Wilhelm von Gloeden | Public domain

From the fetishisation of private space in pornographic films to the democratised, unsugarcoated exhibitionism of the digital age. The images that fill online personal ads have taken sexual imaginary into an unkempt, tacky version of intimacy. Amateur porn removes the filter of traditional manufactured images and abandons classic glamour in favour of a strange ugliness that triggers a mix of fascination and repulsion.

When cult filmmaker John Waters visited Madrid in 2011 as a guest of Rizoma festival, he urged almost everyone he spoke with to check out a website that fascinated him. The site was LuridDigs.com, a blog in which a group of sharp-tongued doyens of good taste wittily and incisively criticise and comment on interior design choices in photos selected from the rich reserve of online personal and dating sites for the gay community. Under the subheading “Horrifying Gay Amateur Interiors”, Lurid Digs invites internet users to divert their gaze from the image of a naked man taking a photo of himself while reclining in front of a mirror, bum in the air, and focus on, say, the incongruence of the inadequate depth of the bookshelves in the room, one of which displays a toy train – a fitting object for a piece of furniture that is clearly not up to the task of accommodating a modest personal library -; or on the greasy mirror surface revealed by the flash in the same photograph, suggesting that “a gorilla had been practicing his kissing technique with his own reflection.” Another image – this time a photo of a middle-aged man lying on a yellow faux leather sofa and performing fellatio on his obese companion whose knee rests on one end of the offending piece of furniture – inspires a hilarious comment on choosing the right colour schemes for our moments of intimacy: “As gay men, we have a moral obligation to teach each other and the rest of the world about flattering colours around which to be nude. These walls ain’t it.” A snapshot of a hippyish young man posing naked, inscrutable, in front of a fireplace elicits an elaborate comment that initially zeroes in on the collection of family photos displayed on the mantelpiece: “the aspirant’s sprawl of family photos (going back to what looks to be Uncle Albert from the mid-1940s) will most certainly work against his odds of getting laid. He might be confused with someone with a family, a life, a heart!” The text concludes that given the various symmetrical arrangements in the room, including two identical navy blue love seats on either side of the fireplace, the homeowner is probably a Libra.

The digital era has paved the way for the democratisation of exhibitionism, but also for a hypervisibility of private space... devoid of all glamour, brimming with awkward domesticity.

Lurid Digs is more than a clever, elaborate joke: it is also symptomatic of the emergence and consolidation of a new imaginary based on the profusion of amateur pornographic and erotic images that are now available online. While the sophisticated erotic films of the 1970s mythologised a whole universe of pop furniture that seemed to mirror the voluptuosness of organic forms – and at the same time festively challenge rationalism –, the postmodern slant of 1980s and 1990s porn films tended to exaggeration and luxury, as in Andrew Blake’s frozen choreographies of desire and the overblown mega-productions by Private Media Group. Now, the digital era has paved the way for the democratisation of exhibitionism, but also for a hypervisibility of private space… devoid of all glamour, brimming with awkward domesticity. As Lurid Digs shows, the relationship between the observer’s gaze and the subject in the image often takes the form of an insurmountable distance that may be purely aesthetic, but is often also a class distance.

On 17 August 2004, LGBT news magazine The Advocate published a piece on photographer Justin Jorgensen’s book Obscene Interiors, which, as the subheading of the article put it, “explores what’s really disgusting about Web porn – people’s furniture.” The book consists of a selection of images from personal ads that Jorgensen found on the web and then edited on Photoshop to erase the subjects’ identities and turn them into them into impersonal, anonymous shapes outlined against a horrid domestic backdrop. His ironic captions for each image – “that couch would be totally great if it was on fire being thrown from a bridge” and “Before you start decorating, it’s important to listen to the empty space… This room is whispering, ‘I can be fun, funky and retro.’ But I’m not sure anyone is listening” – read like a kind of tongue-in-cheek observational essay on the masculine ineptitude for interior decor. Those images of sad flesh offering itself up in various parts of the world share a series of common elements, such as a widespread tendency to display dead indoor plants on pedestals, or to use speakers as corner tables. The outlined figures add a disturbing subtext that the photographer may have been unaware of: they seem to suggest some kind of post-apocaliptic scenario, a global Hiroshima in the wake of an atomic explosion, which could prompt us to wonder whether our lubricious intimacies have left any kind of trace in the places where they occurred.

Another project along similar lines is “Empty Porn Sets” by British photographer Jo Broughton, who took the photos in the series while she was employed as an assistant to porn director Steve Colby, who retired in 2007. With its beds with pink satin sheets and objects such as a dildo, a jar of lubricant, or a high heel meaningfully lurking near the edge of the frame, “Empty Porn Sets” is a kind of eulogy to a pre-digital period that has disappeared for good, in which the fetishisation of the space (in adult films) was essential to the construction of a libertine imaginary.

A quick tour of personal ads and amateur porn – not just gay porn – is enough to convince anybody that terrible taste in interior decor is not just a man thing. Although it is beyond the scope of this text, extensive fieldwork could perhaps identify a causal relationship between the aesthetic inclinations of Spain’s swinger community and the abundance of robust Castilian furniture in the photographs they post on the web.

The difference is that the filter has been removed. The image is no longer a fabrication, and thus no longer a mirage. In this new democracy of lubricity, sex is a flash of hospital light in a lonely room. A lonely, badly decorated room.

Nonetheless, it must be said that in the digital porn age one idea can coexist with its opposite: for instance, anybody who starts flirting with the idea of an inherent incompatibility between IKEA furniture and the pornographic image will soon come across two internet projects that prove them wrong or sow the seeds of doubt. The now-dead Tumblr Just Another Ikea Blog consisted of a collection of (amateur) porn GIFs from various sources, in which all IKEA furniture had been labelled, specifying the model and the price in the company’s signature font. Each image included links to the original video and also to the item on the official IKEA website. The Tumblr was forced to close when the furniture multinational threatened legal action. A similar threat was received by HotMalm.Com, a site that mimics the layout and operation of some of the principal porn platforms in the digital era – YouPorn, PornoTube – but basically consists of various images (human-free) of one of IKEA’s top-selling furniture lines: the Malm bed series. The images link directly to the IKEA site, initially leading users to suspect an imaginative advertising campaign by the company itself. When IKEA publicly expressed its profound displeasure at the site, the company’s spokespersons made it clear that it was not a moral objection to the highly conceptual – and aseptic – nod to the porn imaginary: its reaction was about honouring the trust relationship between the corporation and its customers. IKEA customers must be absolutely certain, they said, of whether or not the message they are receiving is an official notification. Perhaps this response is a key to the secret behind the strange power of fascination of amateur porn – even in the face of horror or ugliness – compared to the porn that had been produced under a corporate or individual brands like Private, Thugson, Salieri, Blake. The difference is that the filter has been removed. The image is no longer a fabrication, and thus no longer a mirage. In this new democracy of lubricity, sex is a flash of hospital light in a lonely room. A lonely, badly decorated room.

Leave a comment