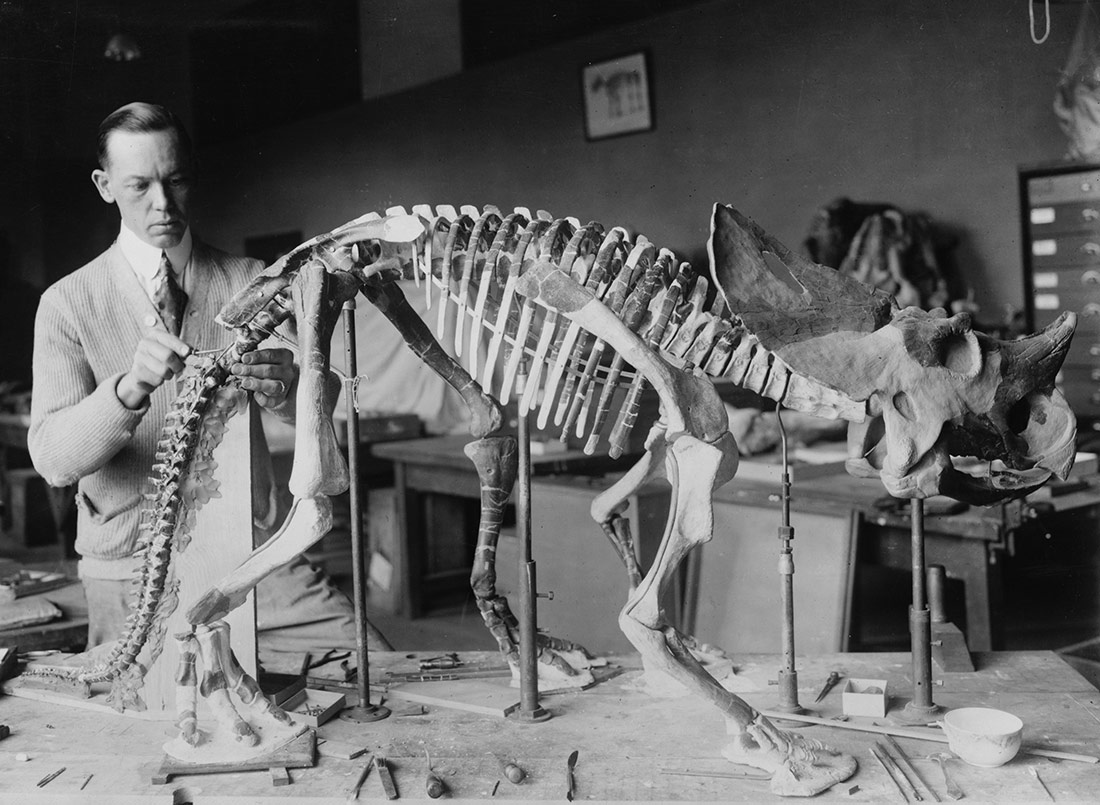

Norman Ross prepara l’esquelet d’un nadó de Brachyceratops per una exposició el 1921 | Library of the Congress | Domini Públic

Data tracking, an in-depth look at a company that produces spying software, discovering someone’s habits based on their browsing history, analysing cyber warfare in independent media or researching the surveillance economy. The first edition of the independent school Freeport opened the doors to a new way of understanding the world. With the thought-provoking title of “Trespassing the data factory,” it proposed an immersion in the compilation, analysis and visualisation of big data, with the aim of narrating reality from a critical, artistic and activist perspective.

“If we do nothing, we sort of sleepwalk into a total surveillance state,” says writer and activist Arundhati Roy, in her book Things That Can and Cannot Be Said (Haymarket Books). But it seems that there is nothing that we can do. Or is there? Social media networks that create profiles with their users’ data. Apps that open up the microphone on a mobile phone to capture football broadcasts from a public venue and, in passing, eavesdrop on what is being said in the place. Technology multinationals that collaborate with government intelligence agencies, supplying them with the private information they request.

In the world of capitalism, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. But despite that, we trust in everything being given away free on the Internet. Apparently. The data market is booming: “It’s the oil of the 21st century,” they’ve been telling us for some time. Our movements have greater value than ever, now that computers are measuring, analysing, selecting, zoning and categorising huge amounts of mass data. Data that reveal moods, behaviours, domestic habits and generational customs. Nothing can resist the potential of machines today.

Algorithms – a magical term that has emerged from the heat of the advances made in recent years – are “the biz” of modern times. Marketing and advertising companies tell us which products we need (or not) in our lives. The question is not about stopping the machinery of capitalism: by using mathematical models loans are granted or refused, workers are assessed and the police detect crimes before they occur. But are they getting it right and arresting the real criminals? Algorithms that redirect electoral votes, monitor health, select the most worthwhile teachers at a school and even help judges to condemn (supposedly) guilty defendants. Don’t they ever get it wrong?

Researcher Cathy O’Neil, in her book Weapons of Math Destruction (Crown), alerts to the fact that these days, poorly designed mathematical models are micromanaging the economy, from advertising to prisons. “They’re opaque, unquestioned and unaccountable and they operate at a scale to sort, target or ‘optimise’ millions of people.”

Five days for waking up and reacting

Opacity causes inequalities: perversions of modern times. The technologies that make us evolve as societies make us regress in ethical terms. Multinationals, the owners of the digital world (and the analogical one, come to think of it) avoid paying taxes in the European countries where they are based and make millions in profits. It’s a well-known complaint but a pointless one since nothing is being done about it. Their power is so immense that they are simply above the laws and established regulations. They know how to track, understand and perceive the magnitude of the data that control everything. We run the risk of being converted into products, selling our own privacy in exchange for a few pennies. Is there anyone worried about this mass surveillance?

From 24 to 29 June, around twenty participants took part in the first edition of the independent school Freeport, with the collaboration of the CCCB and within the framework of the European project The New Networked Normal. “The aim is to create awareness and put very technical tools in the hands of people who are not engineers, or political activists, but that any citizen should be able to master” explains Bani Brusadin, director of Freeport and of the festival of unconventional art, The Influencers. “And especially, awareness of less conventional artists, to expand their intervention,” he adds.

Freeport 2018 | Foto: Paul O’Neil

“Tracking” defines the possibility of quantifying details of behaviour in connected environments; it uncovers the invisible part of the Internet. If private investigators use reverse engineering to work out how a crime took place “forensic cyber tracking” would refer to techniques for understanding the centralisation processes that we are experiencing through digital platforms. “Today Facebook, Amazon and Google dominate world data”, Brusadin says.

The sessions at FreePort were directed by researcher Vladan Joler and his team formed by Olivia Solis and Andrej Petrovski from Share Lab. Share Lab is a research laboratory based in Serbia, and its members include artists, activists, lawyers, designers and technologists. Its aim is to explore the interactions between technology and society. “We investigate threats to privacy, to the neutrality of the networks and to democracy,” Joler explains. At Freeport he raised critical questions about the functioning of the Web and the tracking of each movement, however small it may be.

Participants learned about the compilation, analysis and visualisation of large volumes of data originating from leaks or from public repositories. How? By mapping different Internet providers to understand how they are connected, in which places they are concentrated and in which parts of the world they exercise their power. Applying techniques similar to those used by the American National Security Agency (NSA) to supervise the actions of global companies such as Hacking Team, which creates spying software. Analysing the movements of a journalist based on his browsing history. Or studying the patents of Facebook and Google to detect what they do with personal data. “We explore different methodologies for recognising invisible infrastructures and capitalist surveillance,” explains Joler. And he continues: “We want to show how the people who collect the data act, the people involved in trading and trafficking with data.”

Technological anatomy and radical cartography

Vladan Joler and researcher Joana Moll presented the keynote lecture at Freeport, titled: “Exploitation Forensics: anatomy of an artificial intelligence system”. The anatomical amphitheatre of the Royal Academy of Medicine of Catalonia, located on Carrer Hospital in Barcelona, helped to unsettle people attending as they heard explanations about the social implications, business deals, opacity and environmental destruction of all the companies that intervene during the manufacture, life and destruction of a single mobile phone.

“An iPhone has over ten thousand different parts, which are boxed up by over 300 people in over 700 different territories,” explains Moll, an expert in the environmental footprint left by technology. “Today’s production would be impossible without the maritime transport that has converted it into a global industry.” Moll explains how Bayan Obo (China) is home to the earth’s largest mine of “rare minerals” which make it possible for devices to be so efficient, so light and so small. “But these minerals are running out and they are essential for producing renewable energies.”

It is no coincidence that the largest worldwide manufacture of electronic devices, such as iPhones, iPods and iPads is Foxconn, also Chinese. Joana Moll resents the fact that knowing the devastating effects that programmed obsolescence has on the environment, nothing is being done about it. “But it is logical: it goes against the most predatory capitalist logic. It is the business model of the technology giants. Data are an intrinsic part of the entire current financial system. It is very scary.”

Freeport is aimed at artists, designers, technologists, hacktivists, visual narrators, writers and students from any discipline. For example, Pablo de Soto, an architect by profession but also an activist. He was founder of Indymedia Estrecho in the year 2003, and at the age of 35, he has fought thousands of humanitarian battles on the borders of Palestine, Egypt, Gibraltar and Fukushima. His speciality is “radical cartography”, a social current that emerged to denounce public policies inspired by the Bureau d’Études movement. “Share Lab provides a tremendous insight into the functioning of cyber surveillance. It gives explanations and tools for understanding how to continue,” he explains. “I’m interested in algorithmic governance, understanding the digital layers that move our lives, updating activist mapping in the current social context that is dominated by platforms such as Facebook and Google.”

Maria Pipla studied Journalism and Humanities but wanted more in-depth knowledge about the mechanisms of the digital world. “I registered to combine my artistic research with some technological knowledge,” explains this 24-year old Catalan graduate. “It is very important to assert the materiality of the Internet, the policy of selling information: where are the data stored? The predominant discourses claim that the cloud is very secure, but they are contaminating because in reality it’s not true.” Dutch participant Eva Von Boxtel is 20 years old and studies interactive design. She arrived at Freeport attracted by its consideration of the invisible functioning of the Web. “The debates proposed are thought-provoking, for example the one on the infrastructures of the Internet and the countries that control the connections. We talked about North Korea and about Iran.”

Should we be worried?

In the face of this meticulous monitoring by multinationals and governments, should we be afraid? “There’s no need to become paranoid,” says Bani Brusadin. “We have created this mega-machine between all of us.” According to the director of Freeport, we would have to go back to the “dotcom” crisis, in the early 21st century, to understand how we have got where we are today. “It was necessary for advertising to be viable in order to pay professionals that offered contents or that used it for commercial purposes. It was clear that on the Internet nobody would pay for anything. Ultimately, tracking has turned out to be very efficient for finding out people’s interests and for selling products. With the addition of mobile phones, the perfect infrastructure is present for political surveillance too.”

For Vladan Joler, it is a matter of having the curiosity to find out, “to progress as a society and understand how these mechanisms function and what they involve.” But in an increasingly more complex and invisible world, with the opacity that reigns around us, how can this curiosity be satisfied? “It is not a task that anyone can do alone. It is necessary to bring together a group of people, with the same interests and the capacity to unravel this complexity,” the Share Lab researcher answers.

Researcher Joana Moll is now investigating the transfer of data from dating platforms, such as Tinder. “We have no control over what is happening. Every time you create a profile in one place, you are connected to over 1,500 other platforms.” Looking at the privacy policies of the social networks she has deduced that the sharing of information is massive, without explicit consent. “And there will probably be many more that I have not even reached.” In Moll’s opinion, we should have more governance over our infrastructures and societies, starting with raising awareness among small communities, with examples such as Güifi.net, which are organising themselves to supply Wi-Fi to a large part of the Catalan territory.

“After the Cambridge Analytica case, and the knowledge of the obscure mechanisms that have affected the American elections or Brexit in the UK, much remains to be done. The danger of big data is that it affects the formation of governments. This is why there is all this concern about privacy,” concludes Pablo de Soto. He has hopes in public measures such as those implemented by Barcelona City Council which is promoting the sovereignty of citizens’ data when signing contracts with multinationals or services companies.

“We young people see Internet as marvellous, connected all day as we are to Instagram or Facebook, but in reality, nobody knows what is happening for certain,” says Dutch participant Eva van Boxtel. She criticises the inaction of Europe, especially after the discovery of cases such as that of Cambridge Analytica. “It is quite obvious that the Chinese government controls its citizens via the Internet but… aren’t our governments tracking us in the same way?”

And Maria Pipla asks why it is necessary to live in a world where it is almost an obligation to generate personal data in real time. “Not long from now they will convince us with neoliberal discourses about the benefits of selling our data to multinationals. The quantification of personal life and of life patterns will grow. Is it necessary? What does all that imply?” These are two questions that, in our attempt to answer them, should spark in us an irresistible curiosity for greater knowledge about the technological world in which we are currently immersed.

Pedro Reis | 26 September 2018

Stopped to read at “Algorithms – a magical term that has emerged from the heat of the advances made in recent years” … ppffff. The term algorithm itself derives from the 9th Century mathematician Muḥammad al’Khwārizmī, latinized ‘Algoritmi’.

Leave a comment