A yemeni family walking through the desert to a reception camp set up near aden. January 11, 1949 | Wikipedia | Public Domain

In Europe, the start of the Syrian war put the issue of the refugee crisis on the media agenda. But this situation is just the tip of the iceberg. There are many more political refugees around the world, and they are now being joined by so-called climate refugees, who have not yet been recognised by international legislation. Although there are numerous articles and documentaries on the subject, reliable sources and figures on refugees are still vague: it is a good field for data journalism. Concha Catalán approaches the issue from this perspective, and presents data, resources, and projects from this no-longer-so-new journalistic discipline.

War. Bombs. Hostile soldiers. Fear. Cold. Heat. Exhaustion. Death all around. Anguish. Anxiety about yourself and your loved ones: it is very difficult to imagine what somebody like you sees and feels when they are forced to leave their home, perhaps forever, with nothing except what they can carry, because their lives are in danger.

The world – not just Europe – has been in the midst of a humanitarian crisis since the start of the Syrian war in 2011. Five million Syrians (one in four) have joined the ranks of those from other countries, including three with over a million refugees: Afghanistan (2.7 million, one in 12 Afghans), and Somalia (one in 10) and the Republic of South Sudan (one in 16), with a million each. South Sudan reached the one million mark in the third week of September, and the majority who are fleeing the country are women and children. If you suddenly had to leave, what would you take?

What is a refugee?

A migrant becomes a refugee if he or she seeks the protection of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and meets its criteria. Applicants must be outside of their own country of origin “owing to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”. The UNHCR also tries to help internally-displaced and stateless people. The Barcelona Ciutat Refugi website answers some frequently asked questions on the subject in general and the situation in Barcelona in particular. In Spain, aside from official bodies such as the CCAR/CEAR and ACCEM, there is also a growing number of citizen initiatives, from the BAC network to blogs providing practical assistance.

How many refugees are there?

The number of refugees is equivalent to the sum of the populations of Spain and Romania. In other words, 65 million people have been forced to leave their usual place of residence in order to survive. Around 40 million of these are internally-displaced people who are in their own countries but living in refugee camps or cities other than their own in order to escape armed conflict. 21 million have sought refuge in other countries – including five million Palestinians assisted by the UNRWA –, and 3 million are asylum seekers, awaiting resolution of their case.

Channel 4 News in Britain calculated that asylums seekers in Europe in 2015 had travelled at least 3.2 billion kilometers: and that’s only asylum seekers, only in 2015. To give internet user some idea of these journeys, they created the impressive interactive site Two Billion Miles. The distance covered is the same as 80,000 times around the planet, or 4,000 trips to the moon and back.

In Spain, 6,651 people applied for asylum between January and July 2016. The largest group was from the Ukraine (23%), followed by Venezuela, with Syrians only third, with 17% [compiled by the author. Source].

It is hardly surprising that the number of applicants is so low, given that in Spain only one in 34,522 people is a refugee. In the fifteen years from 2000 to 2014, Spain has only recognised the refugee status of just over 3,600 people, according to data on the UNHCR website that publishes refugee application and resolution figures for all countries [compiled by the author. Source].

Statistics published by the Spanish Ministry of the Interior inform us that asylum was granted to 284 people in 2014, of which 122 were Syrian, and that 2 minors from Algeria where granted permission to reside in Spain (2014 asylum statistics, published in September 2015, latest figures available). There is no official data on the number of refugees in Spain because refugee numbers are not monitored, according to UNHCR.

The shame behind these figures really hits home when we remember that during the first three weeks after the end of the Civil War in 1939, over 485,000 Spaniards crossed the French border, becoming refugees.

The comaparison with Germany is staggering. One in 280 inhabitants is a refugee, and the country accepted a further 138,000 in 2015: 97,000 were from Syria, but there were also 10,000 from Irak and 9,000 from Eritrea. So it seems logical that Germany has processed 435,000 requests for asylum in 2016 so far, 42% of them from Syrians. Looking at another example in Europe, in France one in every 341 inhabitants is a refugee, and last year the country recognised the refugee status of over 21,000 people. An interactive data visualisation by Lucify shows the flow of refugees to Europe, based on the country of origin and destination data entered in asylum applications. As The Exodus Project shows, some refugees are fleeing owing to fear of religious persecution.

But the countries with the largest number of refugees per inhabitant are not in Europe. Lebanon leads the way, with one in five, followed by Jordan, with one in 11, and Turkey, with one in 31. Most of these refugees are from Syria.

And the three countries that have taken in the most refugees worldwide are Turkey, with 2.5 million, and Pakistan and Lebanon with over one million each.

| Host country | 1 refugee / __ inhabitants | Number of refugees | Coutnry of origin | Total refugees |

| Turkey | 31 | 2,503,549 | Syria | 2,539,156 |

| Pakistan | 121 | 1,560,592 | Afghanistan | 1,560,592 |

| Lebanon | 5 | 1,062,690 | Syria | 1,069,924 |

| Iran | 81 | 951,142 | Afghanistan | 979,410 |

| Ethiopia | 135 | 281,508 | South Sudan | 735,474 |

| Jordan | 11 | 628,223 | Syria | 663,294 |

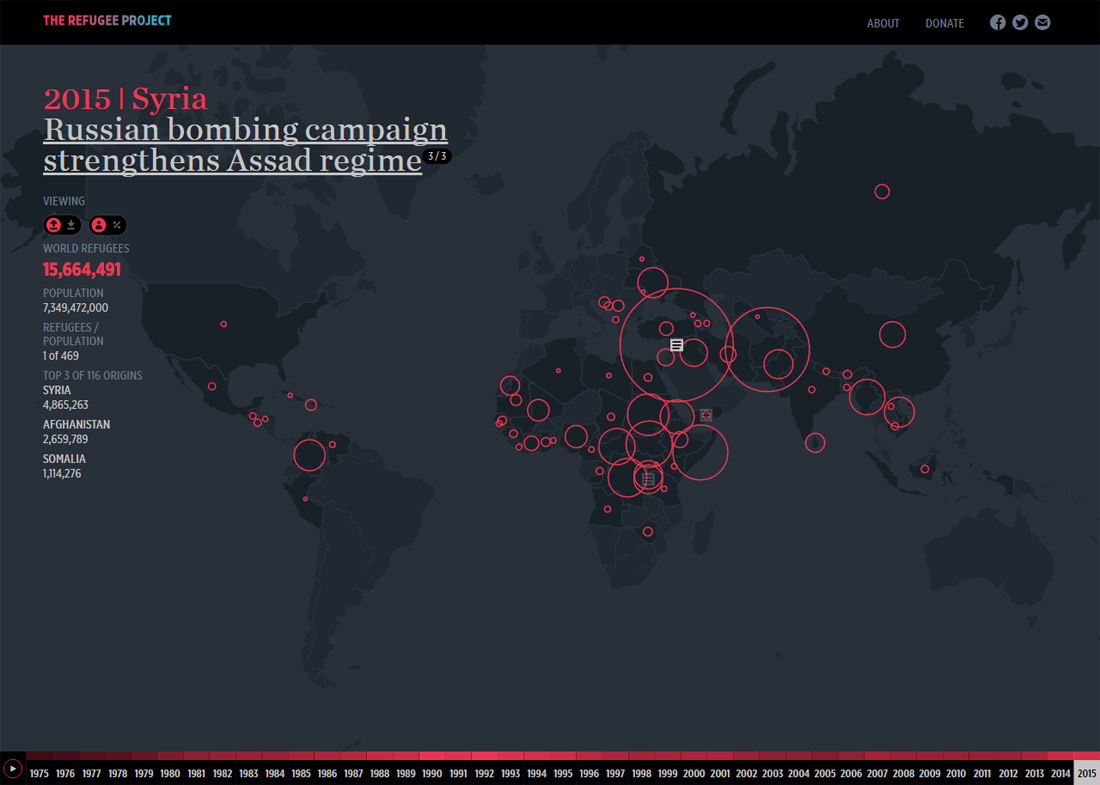

Several data journalism projects have tried to explain the migration flows generated as a result of armed conflicts. The most ambitious and effective online initiative is The Refugee Project, an interactive map that records the movements of refugees around the world since 1975, with narratives that situate them in their individual context. It is important to note that the project only uses the data of people who have been granted refugee status. In other words, the actual numbers are much higher.

Screenshot from The Refugee Project | © The Refugee Project

Is the war in Syria excacerbating the humanitarian crisis?

This is the idea that is being transmitted by the political class and the mass media. Itziar Ruiz Giménez, Doctor in International Relations and former president of Amnesty International Spain, explains that we should look beyond this discourse and consider the three big businesses that are doing well out of this crisis: those who provide border defense security, those involved in illegal migration routes to Europe, and the elites who profit from the presence of people without rights.

In 2011, 20 million people lived in Syria. There were less than 20,000 Syrian refugees, and half of these were in Germany. By 2015 the number of refugees had grown to 4.9 million, with 2.5 million in Turkey, one million in Lebanon, and over 600,000 in Jordan. One quarter of Syrians have become refugees. How has the country changed in that time? You can get an idea here.

According to the UN, 13.5 million Syrians now require humanitarian assistance. 7.6 million of them are internally-displaced persons, 4.8 million are refugees outside the country, and one million have applied for asylum. On 15 September, Amnesty International reported that 75,000 refugees are trapped in an emergency situation at the border between Syria and Jordan, in the middle of the desert. The organisation described the agreement between the EU and Turkey as a “historic blow to human rights” and is investigating abuses against refuges as a result of forced returns.

Where are the refugees?

There are refugee camps managed by the UN, the Red Cross, and NGOs, but many people look for other types of housing. According to information on UN camps, the refugee camps in the countries where Syrians arrive are not the fullest.

| Kenya | Dadaab | 263,036 |

| Ethiopia | Dollo Odo | 214,896 |

| Uganda | Adjumani | 173,650 |

| Kenya | Kakuma | 161,725 |

| Sudan | White Nile Province | 97,505 |

| Argelia | Tindouf Province | 90,000 |

| Jordan | Zataari | 79,074 |

While these are the figures released by the UNHCR, Reuters reports that Kenya is requesting more UN funding to repatriate 300,000 Somalians living in Dadaab, following several annuncements last summer that the camps were to close [Dadaab is actually five refugee camps in one]. Although we use official data to try to understand what is going on, we should not forget that the real migrant numbers are actually much higher and very difficult to calculate.

The UNHCR does not provide data on the the size of the camps, but an attempt to quantify the size of the fourth largest, Kakuma, came up with the figure of approximately nine square kilometres: a little larger than the entire Eixample area in Barcelona [estimated using Google Earth Pro].

Zaatari refugee camp for Syrian refugees in Jordan which only contains a population of 80,000 out of the 1.3 million in the country, July 18, 2013 | Wikipedia | Public Domain

Drowning while trying to reach Europe

Some people look at the Mediterranean and cry, thinking of all the migrants who have died trying to cross it. In 2013, journalists from fifteen countries worked together to create a database of migrants who had disappeared in the Mediterranean. The Migrants Files recorded over 30,000 deaths since 2000, before it had to stop last June due to a lack of funding. The project, carried out with the participation of El Confidencial, won several international awards.

Data and journalism help to provide context and information on the harsh situation of refugees. The United Nations International Organization for Migration (IOM) also compiles information about migrants who have gone missing around the world. A million people reached Greece, Italy, and Spain by sea in 2015, and 300,000 have arrived in 2016 so far, according to the IOM. As of 21 September, 4,369 refugees had died since the start of 2016. 70% of these, 3,213 people, drowned in the Mediterranean. Barcelona now has a memorial in the form of a digital “shame counter” that monitors and displays the number of deaths. Some individuals have also decided to take action, such as the lifeguard Òscar Camps, who set up the NGO ProActiva Open Arms (also on twitter) in Badalona and has become a model for providing practical assistance to refugees. The documentary Astral, due to be released in October, tells the story.

Children

Children are hit hardest by the humanitarian crisis. The photograph of drowned Syrian toddler Aylan Kurdi published around the world on 2 September 2015 raised awareness of the crisis, but little has changed since then. Over half of all Syrian refugees are children. An estimated thirty children die each month while fleeing in search of a better life. In addition, almost 200,000 minors have arrived in Europe on their own, seeking asylum. Some are orphans, others have been separated from their families during the journey. 10,000 children have gone missing during this period, according to an initiative that calls for specific measures by EU member states, and is collecting signatures in support. What does it mean to grow up a refugee? and what do organisations like Mercy Corps do to protect them?

Technology

When refugees reach a safe place, contacting their families becomes a prime concern. Platforms such as Refunite, which has over half a million users, have been set up to help people get in touch through Facebook and mobile phones. And other apps have also been designed to provide assistance.

The aim of this article is to provide information and resources. For specific solutions, we refer readers to the eight suggested by Amnesty International. If reading this leads you to find an organisation that you can contribute to, we will have done our bit towards putting an end to the shame.

YouTube information channels:Amnesty International, ACNUR, Human Rights Watch, the IOM.

* The figures comparing refugee numbers by country of origin and host country are based on UNHCR and UN data for the year 2015. They were taken from The Refugee Project. The data used to compile our own information is based on September 2016 UNHCR population statistics and information from the online and physical press office.

Ann King | 17 October 2016

Thank you for this comprehensive overview. The statistics certainly debunk a lot of the myths and misunderstandings flying around.

Ada Calvo | 17 October 2016

Completísimo. Muy buen trabajo. Sigo impactada por las imágenes de anoche en Salvados. ¡ Enhorabuena!

Àngels Sauret Sumalla | 28 September 2016

M’ha agradat molt l’article!

Jo, com a voluntària del grup de Benvinguts Refugiats de http://www.barcelonactua.org us agraeixo la difusió que feu d’aquest tema, que com a europea, no ens ha de deixar indiferents!!!

Salutacions,

Àngels Sauret

Jose Luis Regojo | 27 September 2016

Impressionant i amb uns enllaços excel.lents.

Leave a comment