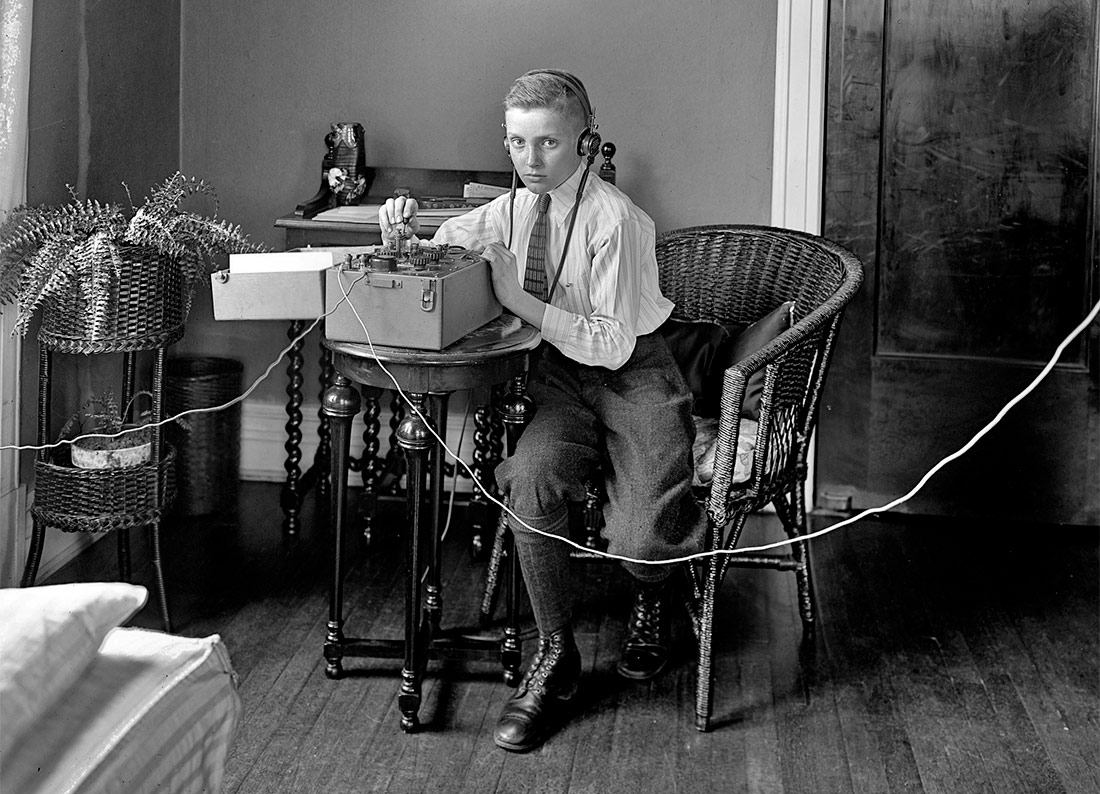

Boy with a telegraph. Washington, D.C., c. 1921 | Shorpy | Public Domain

A home is not made only of bricks and mortar. Its inhabitants transform it and give it meaning, as do the social changes that take place around it. For decades now, homes have been experiencing a technological revolution that has diluted the boundaries between the public and the private, the collective and the individual. Coronavirus has accelerated this process, demolishing the partition walls that separated rest, consumption, production, leisure, and learning… As with other in-depth transformations, its consequences will take time to crystallise, but it is already possible to identify its initial physical and symbolic impacts on domestic life today.

What is a home exactly? In all cultures, life is spent around a place where one can take refuge, cook, keep oneself clean, rest, have sexual relations…. That space can take the most diverse of forms and its uses do not always coincide, but humanity carries out some essential activities around a space, central in people’s lives, that they consider to be their home.

Home is never a finished object. It is always an ongoing work in progress in two areas: the physical – decorating, renovating – and the cultural, according to the changing uses and customs of its inhabitants and their societies. This relationship between the production of space and its symbolic reproduction was broadly analysed in the 1960s by thinkers such as Henri Lefebvre, the situationist movement or Michel Foucault, who describes it thus: “We do not live in a homogenous and empty space, but on the contrary in a space that is laden with qualities, a space that may also be haunted by fantasy; the space of our first perception, that of our reveries, that of our passions…”.

For all these reasons it is no surprise that, since the second half of the 20th century, the mass media first, the Internet afterwards, and now the coronavirus pandemic are radically modifying the form and the meaning of the home.

The end of privacy

The idea of the home as an essentially private place is a modern invention. In the Middle Ages, the concept of intimacy had no currency except for life in monasteries and palaces. Everything in the dwelling was a common space, therefore tables, baths, or beds were taken out and put away, as necessary. Differentiated rooms emerged with the rise of the urban middle class and of individuality as a cultural value. This modified the structure of houses, creating bathrooms, bedrooms, dining rooms, etc. Compartments that guarantee privacy at the same time as ordering how the day must develop, in line with the norms of liberal society.

This notion of intimacy was altered by the communication and technology revolution of recent decades, which blurs the boundary between the public and the private, and also crosses through the rooms of the home. As analysed back in the day by philosopher Javier Echevarría, radio and television converted the dwellings of the 20th century into places where public life is represented. Even if only in a passive manner, news and entertainment installed themselves in people’s living rooms and, with them, so did politics and consumerism. Twenty-five years ago, Echevarría anticipated that with the arrival of the Internet, a new form of cosmopolitanism would arise, domestic cosmopolitanism, given the growing importance of homes for the economy and public opinion.

A quarter of a century later, the development of technology and infrastructures has enabled the Internet to become a resource available in millions of homes. Although this expansion is not equitable (let’s remember that close to 45 per cent of the global population does not have access to the Internet; the figure is 13 per cent in the case of Europe), this all leads one to think that the progressive expansion of mobile technology will end up connecting all dwellings on a planetary scale in the near future.

In the connected home, all the rooms – and not just one – are filled with news, friendships, shopping, teleworking, chats, etc. Telephones, speakers, and other smart electrical appliances are opening up domestic life to the exterior on a permanent basis. If mass media took what is from outside and brought it inside, then digital technology has created a network of insides and outsides that mix and interact with each other asynchronously. The coronavirus crisis has sharply accelerated this evolution, revolutionising homes especially in terms of consumerism, production, and care; with repercussions on the dwelling that are predicted to be physical, but also symbolic and cultural.

Digitalisation of the refuge

Living under a roof is a physical and a psychological need. Homes exist because humans have to rest and recharge their batteries; if possible, in comfort. If the home is a place to which people return in order to rest, what happens when one must remain there by force? The pandemic has obliged millions of people to tackle this contradiction, under the slogan decreed by the public and economic powers of continuing to produce, consume, study, socialise… while awaiting an eventual return to normality.

In recent months, Internet shopping has grown in figures of two or even three digits. According to consultants McKinsey, the increase in electronic commerce reached, in 90 days, what under normal conditions would have required 10 years. Hygiene and social distancing measures continue to dissuade visits to physical shops, and everything points to this tendency becoming consolidated over the coming months, making the relationship between housing and the digital market even more porous. The most evident materialisation of this process is the generalised presence of delivery staff and riders on city streets, which also shows how the connected home, above all in its lockdown experience, could not exist in the way that we know it without the labour precarity imposed by some digital economy companies such as Amazon, Deliveroo, Glovo, etc.

Technology has also facilitated the hurried transformation of the home into a production centre for certain types of professionals and providing that a good Internet connection is available. This has caused three types of tensions: the first, in terms of space, which as is detailed below, has generated important changes in the uses and distribution of the home; secondly, in terms of time, calling into question the already fragile state division between working and leisure hours, which digital communication has spent decades cracking; the third, which takes something from the two previous tensions, is related to care, as teleworking with dependent elderly people or minors introduces into the home the as-yet unresolved conflict between the production mandate and that of people care. These disputes have an especially severe impact on women and girls worldwide, who during the pandemic have increased their time devoted to housework and who, among other inequalities, suffer the digital divide to a greater degree.

Moving home because of the virus

A dwelling can be interpreted as a symbol of the society surrounding it, a metaphor of its unwritten laws. “Buildings force us to act in a determined way”, wrote historian Peter Burke, “but they give ‘indications’ to the people who live in them, encouraging all kinds of behaviours”. The experience of the pandemic, its challenges and the needs created, have already evidently transformed the public space, but also the private space, in both physical and cultural terms alike.

In the material plane, lockdown and teleworking have increased the value and usefulness of galleries, courtyards, terraces, balconies, and other types of open spaces that multiply, even if only symbolically, the habitable horizon of homes, and that the pressure of the property market has gradually reduced. This need for perspective with respect to the immediate environment and the possibility of remote working has led to renewed interest in homes outside of the big cities, a tendency that is probably not due to the search for more square metres, but of a lower urban density that provides a sensation of control and independence from the exterior.

Interior spaces changed and will change while the threat of new lockdowns remains latent. In the labour sphere, a survey by HP confirmed that, because of coronavirus, European workers have spent an average of 500 euros on conditioning a workspace in their homes. The spend is shared principally between office furniture, printers, headphones with microphone and improved Internet connection. It seems sensible to think that these new connected spaces will become permanent, altering the structure of the dwelling for the benefit of more versatile and flexible rooms, where technology permits working, studying or the pursuit of hobbies, as necessary and with a certain degree of comfort. This is the metamorphosis of the home as a centre for production, education, and online recreation.

Household policies

These changes in use and customs facilitated by technology anticipate a transformation in the cultural plane also. Consultants Accenture have christened the years to come as “the home decade” because, according to a survey in which close to 9,000 people have participated across 20 countries, the sensation of discomfort and distrust in the hygiene of public spaces, the end of non-essential travel, the fear of the financial crisis and a fall in family income could mean that people spend increasingly more time in their homes and opt for local consumption.

The political consequences of this situation have a potential as dystopian as it is emancipatory. Philosopher Paul B.Preciado warned at the start of the state of alarm in Spain that lockdown was the importation to the very door of the private home of security and border protection policies trialled for years with migrant people. In contrast, other voices seek among the undergrowth new possibilities for action both individual and collective: increased value of care work, the emergence of local mutual support networks, a revision of consumerism and a renewed look at nature and the environment.

As usually happens in these cases, the final nature of these changes will depend on people’s capacity to get ahead of them and scrutinise their governments. The consolidation of the dwelling as an economic, political, and cultural space expanded by the technology now seems inevitable, therefore the challenge is now how to maintain a civil society whose members now live in an interconnected way but are forced to take refuge in their own homes.

Leave a comment